Topic: AIF - DMC - Scouts

Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance, Part 10

Frederick Allan Dove

3rd Light Horse Brigade Scouts in the hills at Tripoli, December 1918

In 1910, Major Frederick Allan Dove, DSO, wrote a book on a subject he was very familiar with through practical experience called Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance. This book set the intellectual framework for the formation of the Brigade Scouts during the Sinai and Palestine Campaigns as part of the Great War.

Dove, FA, Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance, 1910.

5. - Finding One's Way. General Remarks.

The Scout who gets lost is worse than useless. How is one to learn to find the way out and back in strange country and at the same time take all precautions against being killed or captured? By cultivating the powers of observation; developing the bump of locality; learning to read a map; understanding the use of the compass; and thoroughly realising the value of the sun, moon, and stars as guides. There are wonderful tales told here and elsewhere of the extraordinary feats of bushmen in travelling across country. In Africa, our best bushmen were frequently "bushed" in an absolutely open treeless country, probably the easiest in the world to keep one's direction in. Our bushmen only excelled the regular troopers in detached work in their faculty of observation of landmarks, thus being able to find their way back, and in a greater amount of craftiness in the presence of the enemy. When it came to sending a patrol from the camp to a drift, we will say, twenty miles away and south-east as the crow flies, starting after dark in entirely new country, there was something more than mere bushcraft required from the patrol leader, and that something was training and education. It is, of course, much easier to impart this training to a man who has been brought up in the country, accustomed to ride long distances, and hunt wild animals or muster stock, than it would be in the case of a city-bred man. Nevertheless, one or two town-reared youths became among the few very reliable Scouts that I had on service.

(1) Finding the Way Back Over a Route Already Traversed.

In this case the "bump of locality" is all-important.

During the outward journey mental note is taken of the general direction of the journey, the relative situation of landmarks, the general slope of the country, the direction the water runs. With practice, one gets to note all these almost unconsciously, together with many smaller details, such as the class of vegetation-here white gum predominates, further on a belt of ironbark, along the hollow oak trees are noticed ; the construction of fences; variations in the nature of the soil ; outcrops of rocks, and so on.

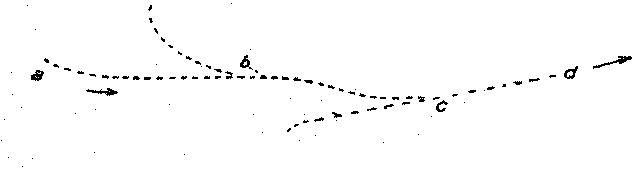

The Scout who is at all doubtful about finding the way back should occasionally halt and look at the way he has come. In bush or scrub country, when following a road or track, be careful to note other tracks joining your route at a small angle, thus:-

a, b, c, d is the outward road. At b and c, other tracks join it. The Scout going from a to d is not likely to notice these unless he is vary observant; but coming the other way back he is sure to see them, and may be confused as to which is his right road. To sum up, the "bump of locality" is a result of a trained and practised habit of observation.

(2) Coming Back by a Different Route.

In an enemy's country the Scout can seldom risk coming back the, way he went out, especially through defiles, passes, or fords. He must choose a different route. Again his habit of observation of landmarks, car., will greatly help him. His training in map-reading also is of use here. A patrol goes from

a to b about ten miles. There is a dangerous spot at c that the leader wants to avoid when returning. He moves out to d and then heads for camp. A little, diagram as I have drawn it and a brief calculation will enable him to strike his direction near enough for practical purposes, as on approaching the camp or outposts lie will be sure, to recognise landmarks. There is one thing requisite here, viz. that he should always have a pretty accurate idea of the distance travelled. I always did this by judging my rate of movement and noting the time taken from point to point. There is no better way that a know of unless you can identify your position on a map. Then, of course, everything is easy.

If his “Map Memory" has been developed, he can then close up the map and put it away, but for hours afterwards he has a complete mental picture of his intended route, with all adjacent topographical features. When launched on his journey he knows - here to look for hills; where to expect watercourses and how the water runs, if any; when he will strike a well-marked road, a railway, or a telegraph line; where there are bridges, swamps, and gullies; what villages or habitations he must avoid.

The would-be patrol leader must know that the only reliable map may be the property of the General, and that he will be lucky to be allowed five minutes' study of it; that even if he have a good map he cannot be constantly pulling it out when Scouting by day, and that at night it is almost impossible to refer to it. Therefore, cultivate the "Map Memory."

(4) The Use of the Compass.

This is sufficiently dealt with in the Manual of Field Sketching, and is easily learned in a few minutes.

(5) The Sun, Moon, and Stars.

A little instruction and practice will render the patrol leader independent of the compass so long as he can see the sun, moon, or stars. As to the sun: we are taught ill childhood that the sun rises ill the East and sets in the West. This is only true, however, at the time of the Equinoxes - that is, on the 21st of March and the 23rd of September in our (Southern) Hemisphere the sun rises.

(3) Finding the Way to a Given Point in Strange Country.

The chief aid in doing the above is what may be called "Map Memory." This can be cultivated in peace training. When acquired, it is invaluable to a Scout. What I mean may be explained thus: Before starting on a reconnaissance the patrol leader has a map spread out before him. He is told, or shown, or finds out where his present position is and the place lie has to go to. He studies the map for a few minutes and decides on his route further and further north of East (and sets north of West) from March 21st to June 22nd; then gradually rises and sets nearer East and West respectively till about September 23rd. After that it rises and sets south of East and East till about December 22nd, and then works back again. It may be taken that at 12 noon the sun is always due north and that all shadows point due south. By occasional observation and study for a few weeks one can get estimate accurately enough the bearing of the sun at and hour of the day, providing one has a watch; or vice versa, if one has a reliable compass and a table showing time of rising and setting of the sun, one can always tell the time. When marching by the sun (or by the shadow cast by oneself, or trees, etc.) regard must be had to its apparent motion from East to West.

The movements of the moon should also be studied, and particularly so when one knows that one may be required to go on patrol any night. Its time and direction of rising and setting should be known. Only twice in the month does it rise in the East and set in the West. It rises nearly an hour later each night. Almost every almanac contains the times of rising and setting of the moon.

The stars are the most reliable guides at night. It is not necessary to have even the slightest knowledge of astronomy. But the Scout should have a sort of nodding acquaintance with the principal constellations. Their names don't matter at all - get to recognise them as you do the face of a man you often meet, yet do not know. The most conspicuous of our constellations is the Southern Cross. Near it are the Centaurs (the "Pointers"), it must again be remembered that the stars, like the sun and the moon, have an apparent motion from East to West. The position of the Cross at different times and at different hours on the same night should be observed and noted. It will be seen that it is high in the heavens in the winter and low down in the summer months. On the same evening at different hours it will be seen not only to have moved but to have changed the inclination of its longer axis toward, the horizon. The following diagrams are sufficient to shoes how the position of South may be estimated from the position of the Cross:

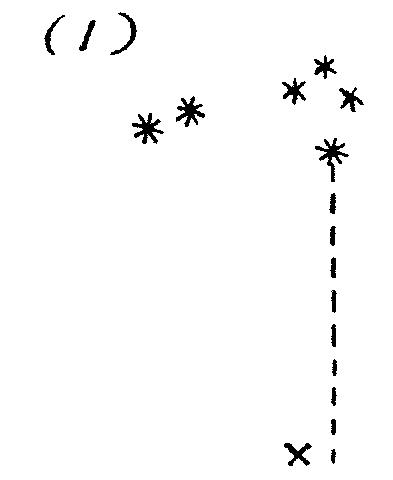

(1) The "Pointers" and Southern Cross.-The Cross about upright. x is the approximate position of South; got by prolonging the main axis of the Cross 31 times, then a little to the left.

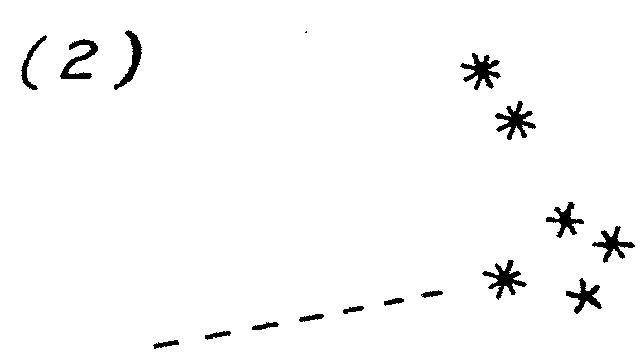

(2) The Cross on its side. Note position of “Pointers."

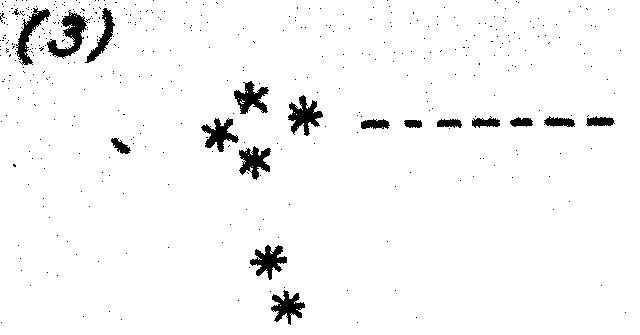

(3) The Cross on its side. Note the position of the "Pointers."

The relative brightness of the stars is shown by the number of rays.

The young Scout should got a sailor or other person who knows to point out the following: - Orion, Sirius, Canopus, Scorpio, Achernar, The Milky Way, Aldebaran. It will happen often when patrolling at night that Southern Cross may be temporarily or permanently hidden by clouds, but that there are patches of clear sky elsewhere. Hence the necessity of being able to recognise other star-groups.

In marching by the stars, one must allow for their apparent motion from fast to West. For further instructions vide Manual of M.R. and F.S., page 61.

Previous: Part 9, Scouting For Information

Next: Part 11, Avoiding Detection

Further Reading:

Obituary, Frederick Allan Dove

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: Brigade Scouts, Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance Part 10 Finding One's Way