Topic: Militia - LHN - 1/7/1

NSWL

New South Wales Lancers

History, 1897-1900

New South Wales Lancers [1885 - 1903]

1st (New South Wales Lancers) Australian Light Horse [1903-1912]

7th (New South Wales Lancers) Australian Light Horse [1912-1919]

1st (New South Wales Lancers) Australian Light Horse [1919-1929]

1/21st Australian Light Horse [1929-1935]

1st (Royal New South Wales Lancers) Light Horse Machine Gun Regiment [1936-1942]

1st (Royal New South Wales Lancers) Armoured Regiment [1942-1948]

1st Royal New South Wales Lancers [1948-1956]

1/15th Royal New South Wales Lancers [1956- ]

[The elephant's head used on the badges is taken from the family crest of Lord Carrington, Governor of New South Wales from 1885 - 1890 and was appointed Honorary Colonel of the Regiment from 1885 until 1928.]

Tenax in fide - Steadfast in Trust

Allied with: King Edward's Horse (The King's Overseas Dominions Regiment).

The following history is extracted from Vernon, PV, ed., Royal New South Wales Lancers 1885 to 1985, Sydney 1986, pp. 24 - 39.

CHAPTER 2 - PROGRESS 1897 to 1900

QUEEN VICTORIA'S Jubilee was celebrated in 1897. Reviews and parades of the armed forces of the Empire would undoubtedly be an important feature of the celebrations, and it is not surprising to find that the opportunity was well and truly seized by the enthusiasts of New South Wales. On April 10, a representative detachment, including Lancers, Mounted Rifles and Permanent Artillery embarked on the P. & O. steamer Ballarat, the Lancers under temporary command of Lieutenant Cox, Captain Vernon being detained by business until a later date.

A Memorandum of Rolls dated April 15 1897 records the personnel of the detachment: Lancers, 33; Mounted Rifles, 42; Permanent Artillery, 56; total N.S.W. troops, 15 officers, 116 other ranks; also nine submarine miners already in England undergoing training. Extracts from General Order 68 of April 6 1897 give further interesting details:

"Detachment of N.S.W. Lancers for the purpose of undergoing a course of Military Instruction with the Imperial Troops and taking part in the Military Tournaments. Expenses to be borne by the Regiment. Procession to wharf, 4 horsed guns, Lancer and Artillery Bands, a Squadron of Lancers, Lancer Cadets, Artillery and Engineer Troops, baggage-waggons; all under Lieut-Colonel H. P. Airey, D.S.O. The tender of Jas McMahon and Co. accepted for supply of horses for the Brigade of Field Artillery 1897."

The A.A.G. at this time was Colonel H. D. Mackenzie, whose son, a member of the Sydney Half-Squadron, was included in the jubilee detachment.

As in 1893, the detachment went overseas entirely at its own expense, and it is interesting to note the particulars of subscriptions contained in a newspaper cutting of the day. Though unfortunately incomplete, this cutting indicates "the enthusiasm and interest that was aroused by the occasion". The subscriptions, totalling £1,223, included: Major Burns, £250; Berry Half-Squadron, £205; Casino-Lismore Squadron, £225; Singleton Half-Squadron, £50; Maitland Half-Squadron, £40, with substantial sums from some of the troopers. Public functions to raise funds included a Military Promenade Concert, held at the Sydney Town Hall on April 9 1897, under the patronage of the Governor and Lady Hampden, the Admiral and staff, the Lord Mayor of Sydney and the Major-General Commanding arid staff. Tickets were sold for 3/-, 2/- and 1/-. The pound being worth very much more in those days than it is now, it will be realised that this amount, with various additions, represented a very useful contribution towards the heavy expenses that such a detachment inevitably must incur.

The Agreements of Service were made between each member embarking and Major J. J. Walters, Major James Burns, Captain W. L. Vernon and Captain George Lee for six months' service, and contained amongst many others the following provisions:

(4) The C.O. shall have the power to discharge the member at any time and at any place without notice and without entitling the said member to any compensation or remuneration by way of damage or otherwise.

(6) The member shall serve in the said detachment without pay.

(10) The member shall be deemed to be engaged as a private in the detachment, notwithstanding he may be appointed to a higher rank.

(11) The C.O. has power to reduce any N.C.O. in grade or to the ranks.

(13) The member to remain subject to the "Volunteer Force Regulation Act, 1867" and, when serving with Her Majesty's regular forces, to the Army Act.

The following is the nominal roll of the detachment, with some notes on the later careers of the members:

Regimental Staff

Staff-Sgt G. E. Morris, D.C.M. in South African War, and later captain and adjutant.

Sydney Half-Squadron

Capt. W. L. Vernon, Regimental Commander, and Commander 2nd A.L.H. Brigade.

Lt F. H. King, Captain.

Lt F. C. Timothy, Lieut-Colonel, M.T.O., Egypt, 1916.

Sgt J. McMahon, Regimental Commander.

Tpr J. J. Anderson

Tpr A. J. Morton, Lieutenant.

Tptr K. D. Mackenzie

Parramatta Half-Squadron

Lt C. F. Cox , Regimental Commander; Commander 1st A.L.H. Brigade, A.I.F.

Sgt-Maj. R. C. Mackenzie, Regimental Commander.

Sgt P. F. O'Grady, Permanent Staff.

Sgt R. A. P. Waugh, Lieut-Colonel in A.A.M.C..

Cpl E. A. E. Houston, D.C.M. in S.A. War; Captain.

Tpr R. E. Harkus, Died in S.A. War.

Tpr W. H. Hillis, S.A. War; N.S.W. police.

Tpr F. S. D'A. Macqueen, Lieutenant.

Tpr P. Pritchard

Tpr F. W. Todhunter

Tpr Watts, S.A. War.

Berry Half-Squadron

Tpr J. Daly

Tpr J. S. Dooley, S.A. War; lieutenant.

Tpr W. Moffitt, S.A. War; Lieutenant.

Tpr W. Lumsden

Tpr J. Wilson

Maitland Half-Squadron

Sgt J. C. Mackenzie

Cpl H. E. Sparks

Singleton Half-Squadron

Sgt C. J. Williams, S.A. War.

Cpl A. G. Brady

Casino Half-Squadron

Tpr J. W. Campbell, Sergeant in S.A. War.

Tpr J. J. Riley

Tpr H. A. Robinson

Lismore Half-Squadron

Tpr A. T. Sharpe

Tpr P. Sexton

Arrived in England, the members of the detachment were quartered at the Chelsea Barracks. As they went abroad in London, they evoked much favourable comment, and, as in 1893, they distinguished themselves in the tournament ring. Out of five Empire Gold Medals allotted at Islington, Sergeant Williams won the one for tentpegging and Trooper Ben Harkus the one for lemon cutting. The competitions were in three groups, one each for regulars, auxiliaries and colonials. The Empire Medals were for competition among the first prize winners of the three groups. Two of the Empire Medals went to the N.S.W. Lancers, one to a Canadian and two to British Army competitors.

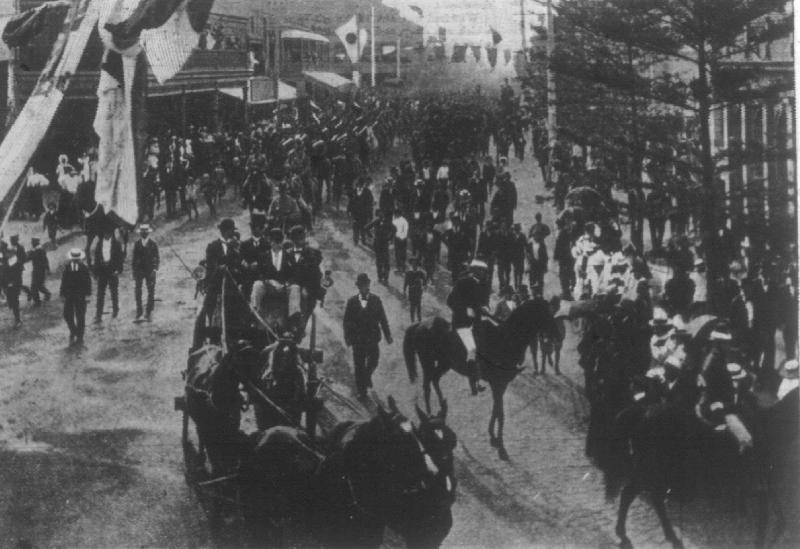

There was no lack of festivities during this tour. The people were celebrating the record reign of their Queen, and the doors of English hospitality stood open. The fine physique and gallant bearing of the Australians endeared them to their British comrades-in-arms, and their natural friendliness made them welcome visitors in innumerable British homes. No sight could have been more dazzling than the jubilee Procession in London. Troops from every corner of the Empire marched; foreign royalty attended; dignitaries and deputations of every persuasion swelled the throng. And, in the Daily Chronicle, the N.S.W. Lancers were described as the "flower of the Procession".

One of the most memorable excursions made by the Lancers was to High Wycombe, at the invitation of Earl Carrington, the honorary colonel. There was a parade of the local troops to welcome them, and the detachment presented the mayor with a lance, which was displayed on the wall of the town hall. Two more lances were presented to the vicar, and these were hung over the architrave of one entrance of the parish church.

Jubilee Medals were presented to the members of the detachment on July 3 by the Prince of Wales, and on August 26 they embarked for home on S.S. Himalaya. The experience, training and military temperament gained were of incalculable value, setting a new tempo for the entire regiment and offering yet another basis for sound friendship between squadrons during subsequent camps. And although the future could not at this time be foreseen, it is clearly evident today that the contacts with British troops, and the wider, richer military life glimpsed during this expedition was to stand the Australians in good stead within the next few years.

At a dinner given at the Sydney orderly room in October 1897, Captain W. L. Vernon gave an account of the doings of the Jubilee Contingent, and was cheered with enthusiasm. The Evening News of October 12 reports Captain Vernon:

"I travelled from England in August with General Sir William Lockhart, Commander-in-Chief of the forces operating against the tribes in the North West (Indian Frontier) ; also with Lord Methuen, who was going to the front. General Lockhart invited me to go to the front, but owing to the Government giving leave of absence for the trip only, I was unable to accept. General Lockhart said that if any Australian officers were sent to India, he would take care they would have opportunities of seeing everything, and by express request of the General, I have communicated this to Major-General French (commanding the N.S.W. Forces) . It has been said here the position of affairs was not serious enough in India to permit of the Lancers going, but it might happen to be so some day, and then instead of a squadron I would like to see the whole regiment offering."

Captain Vernon was followed by the Rev. G. North-Ash, for many years loyal padre to the regiment. The padre spoke of priests advancing in the van, and elaborated with glowing historical allusions, with the result that the newspapers next day chastened his Cromwellian aspirations as being more persuasive with burning brand and musketoon than with texts!

These stirring events served to rouse the fighting spirit of the regiment to a pitch that made the members of the jubilee Contingent very reluctant to content themselves with civilian life, weekly parades and any escort duty, tournament or review that might eventuate. Full-time soldiering seemed to be the only acceptable answer to their restlessness.

Lieut-Colonel Burns felt strongly that the regiment needed the maturing experiences of service outside its own familiar territory and one of his first acts was to circularise his sub-unit commanders, sounding them out on the possibility of raising a detachment for service in India. Colonel Burns maintained that "the Imperial Government require cavalry," that "the N.S.W. Government would also at small cost have their men experienced in active service" and that "the regiment would itself be much benefited; probably get Imperial pay, some 8/9 a week, and a good market for their horses in India."

A file of telegrams received in answer to this circular indicates the feeling of the various units:

Lt A. Hay, Berry "No difficulty 12 or 15 men and horses."

Capt. McEvilly, Robertson "Do not favour India or Imperial pay."

Capt. Bowman, Singleton "12 men likely to volunteer, no officers."

Capt. Markwell, Maitland "Little hope of getting men to volunteer."

Capt. C. E. Taylor, Lismore "Strongly in favour, probably 10 volunteers."

Capt. F. G. Fanning, Casino "Men will go India."

Lt Cox, Parramatta "Easily get 10 or 12 men."

When this offer went in, however, the whole idea was quashed by the Premier, Mr George Reid, whose only knowledge of soldiering, besides driving with the contingent in the jubilee Procession, was a memory of the Sudan Contingent, 12 years earlier, and that only an experience of patrol skirmishes. His reply was that he "did not wish to see a spirit of unrest and military adventure grow up in this country." Colonel Burns was obliged to wait another year for an outlet to his ambition to make his regiment efficient-efficient in the only true meaning of the term, through knowledge of the rigours and realities of active service.

Soon after gaining command Colonel Burns had set about transferring the band from West Maitland to Parramatta, the seat of regimental headquarters and this was accomplished in 1898. The strength was increased from 17 to 25; fresh horses, instruments, saddlery and music were purchased at the expense of the officers. Assistance in finding homes and new employment was given to those bandsmen who were agreeable to moving to the Parramatta district. One of these was A. E. Taylor, who had joined when the band was raised in 1891 and who was to become bandmaster from about 1909 to 1941 - 50 years of unbroken service in the band.

About 1899 the Sydney and Parramatta Lancers were issued with military saddlery as they were so often called upon to provide vice-regal escorts. During the South African War, however, all available military saddlery had to be called in to equip units going on active service. It was re-issued at the close of the war.

The annual camp of the New South Wales Militia in 1898 was held in April at Milkman's Hill, Rookwood. Besides the Lancer Regiment, the Mounted Rifles Regiment and "A" Battery, Field Artillery, the Mounted Brigade took in the newly raised 1st Australian (Volunteer) Horse. Permission had been given tardily in June 1897 to raise this additional cavalry regiment and it had been gazetted in August with an annual capitation allowance- of £5 per head. The founder of this regiment, Lieut-Colonel J. A. Kenneth Mackay (formerly of the West Camden Light Horse) was given command, and R. R. Thompson of the Lancers was gazetted 2nd lieutenant and appointed adjutant. Despite an acute shortage of members with any soldiering experience, drilling had been going on in the country districts. The men marched into camp in civilian clothes, but the 400 myrtle green uniforms ordered from London arrived just in time to be served out for the first parade. A heavy shower of rain during the parade, however, caused consternation in the ranks; every man in the regiment was dyed green! In this camp the field fighting was very fast for the limited amount of country available. The contact troops gained good training from it, and compared with some training in later years it was of particular value to the N.C.O's. Owing to limited space there was not much scope for the tactical training of officers. The men were very hardy and took no notice of discomforts.

During this camp, the previously projected idea of a term of intensive cavalry training at a home station (i.e., in Great Britain) was debated by the officers. It was felt that the members who went would be able to subscribe the funds for fares, uniforms, etc., the remainder to come by subscription from officers. But Imperial pay would be needed during the training, and it was hoped the New South Wales Government, who would draw great benefit from the project, would vote up to half the cost. Major-General French, the Commandant, approved heartily but Cabinet would do nothing.

The Imperial Government at this time was considering interchanges of troops with the colonies. Its plans, however, did not eventuate. It was Colonel Burns himself, in London later in 1898, who arranged for a squadron of one hundred to be quartered, fed, horsed, and trained at the chief cavalry centre. Lord Carrington, the honorary colonel of the regiment, and others in England subscribed about £500; on his return, Colonel Burns opened a fund with £300, and the other officers and patriotic well-wishers subscribed another £2,000. The subscriptions were still £2,000 short of the target, but £2,000 roughly equalled the passage money (steerage). The position was put before the units, and it was found that each applicant for training was quite ready to pay his fare of £20. Many of the men took substantial sums of money in addition, one country lad owning to a present of £100!

Fortunately the Government's disapproval of the detachment's departure was swept aside by some correspondence from the Imperial Government. Letters from the War Office and Mr Chamberlain, then Prime Minister, asked the New South Wales Government for particulars as to the number of men they were about to send over for training. Their hand was forced and they gave consent for the departure with a somewhat bad grace. The despatch and maintenance of the troops, said the Government, must not entail any expense to the public. Nor was any expense to the public incurred, except when war intervened.

It was decided that the period of absence should be six months, following the arrival in England in the early spring of 1899. Hard work and rigorous training would be the order of the day, both officers and men realising that everything that they learned would be of value to their regiment. No leave was to be granted, except a fortnight for all at the termination of training. The programme was to include the annual Salisbury Plains manoeuvres, and the entire six months was to be spent under the soldiering conditions laid down in the N.S.W. Volunteer Regulation Act and in the Imperial Army Act. Each man signed a nine months' "agreement" with Colonel Burns, and he was also required to remain at least two years in the regiment afterwards, in order to hand on the benefits of his experience.

On and about February 20 1899 the members of the various units arrived at the Lancer Barracks, Parramatta, and pitched their tents on the old parade ground used by the Imperial regiments for half a century. At the second morning's parade four sergeant-majors and sergeants picked men in turn until the four troops were constituted. They seemed to pick in order from tall to short, the troopers not being well-known to more than one of them. The result was an averaging in size, and although many of the home localities were partially obliterated, this method minimised the tendency to form cliques. The troops were led by 2nd Lieutenant S. F. Osborne, Berry; 2nd Lieutenant W. J. S. Rundle, Maitland; and the S.S.M. and S.Q.M.S. or their sergeants.

The preliminary training was in sword, lance and carbine exercises (sentry duty as usual was performed with the lance). The 30 grey band horses were run in and riding tests and school gone through. All but a few were good horsemen, brought up in the saddle, and by the second parade they knew which band horses to side-steel The horses returned to grass a fortnight later, bewildered, but better fed than usual. Nevertheless, the name "Hatracks" stuck to them ever after - in some cases unfairly.

From the reminiscences of H. V. Vernon, then a trooper, the following extract gives a vivid picture of the scene:

"Visualise the rough happy crowd just on the eve of adventure. Few had been on a ship; though some were well drilled and soldierlike, the majority were not; about five wore jubilee Medals; none had ever seen active service. As is usual with Australian soldiers, perfect friendship reigned throughout."

Nicknames had already been bestowed with rapidity, thoroughness, good humour and that typical Australian sense of democracy that allowed no discrimination. Most of the names stuck, to both officers and men, though in a few cases future events produced a better or more up-to-date effort.

The uniforms, though attractive, were not well cut. Hats were worn with red puggaree and cock's plumes, the regimental badge on the upturned side. Jacket, breeches and overalls were made of the good N.S.W. brown, reddish-tinged cloth of that day. The jacket was fairly good; breast pockets only, elephant's head badges on the collar and N.S.W. Military Forces buttons. The breeches were close fitting, and breeches and overalls had the double red stripe, except in the case of trumpeters and bandsmen who wore double white stripes. Leggings were of the "slip-on" or "stovepipe" variety, fastened by a strap under the instep, while the boots were elastic sided "Jemimas" - "handy for getting on quickly," writes Trooper Vernon, "but hopeless for field use". The solid nickel spurs were a source of envy to the cavalry in England, and the flat field service cap was of "N.S.W. brown" and red, with white piping. The full dress Lancer tunic, leather gloves, red and yellow girdle were part of the outfit; also the white lines which, tradition has it, are the survival of the cords carried in former times for tying prisoners, "and in which the recruit," he remarks, "for some time continues to tie himself”:

"For fatigue work," he adds, "we were served out with a tight thin blue jacket and pants which only required the broad arrow to complete them. Incidentally, I recollect the disgust on passing through Melbourne when a fatigue party of us to draw stores was sent to wait in this get-up for about an hour, at the corner of Bourke and Swanston Streets. In Aldershot, however, they were found to be a necessity for `stables', drill order being taboo."

The accoutrements of the day were the blancoed shoulder belt and black pouch, the latter used for transport of "fags", blancoed sword belt with slings, the slings being billeted together when without sword. Arms were the Indian lance and pennon, sword and steel scabbard with blancoed knot. Martini-Enfield singleshot carbines, sighted to 800 yards, very accurate and light, were carried without slings, and a list of small kit and items was issued, each man fitting himself out independently. In Aldershot only officers normally were permitted to wear civilian clothes when on leave out of barracks. In fact, the penalty for infringing this rule was extraordinarily severe. "I recollect a man of the 6th Dragoon Guards," the reminiscences continue, "caught in `civvies' at Farnham, some five miles away, being given two years' gaol by court martial for this offence." An exception was made, however, for the Australians, and civilian clothes were included' in their kit. No horses or saddlery were taken.

Four days after assembling, a night display by the full squadron was given at Victoria Barracks at a Band Tattoo, and 12,000 people were present. On March 3, anniversary of the first public parade of the Sydney Light Horse and the embarkation of the Sudan Contingent, 1885, the squadron marched with the band from Paddington to the Quay. From here they were ferried by launch to the S.S. Nineveh at Dawes Point. Few had been in a ship before, but the rigging was manned as on all transports.

The following sidelights on the voyage to England are given in the reminiscences:

"The Singleton men brought a kangaroo and an emu. The latter, not being able to withstand a diet of polished buttons and badges, eventually died, partly from swallowing a two-and-a-half inch pouch belt star. The kangaroo (`Jumbo') fell 40 feet down the hold at Melbourne and led a hopeless life in Aldershot until presented to Lord Carrington for the park at High Wycombe. The programme of the Royal Military Tournament, Islington, in May and June, entered them both as 'dramatis personae'."

Tenerife being a Spanish colony, a change from uniform to "civvies" was ordered for troops going ashore, and, naturally enough, the type and cut of clothing temporarily broke up old groups and formed new. Stocks of fruit and tobacco were bought ashore, the fruit making a welcome addition to the somewhat monotonous ship's diet.

Fifty-six days out from Sydney, the Lancers arrived in London. And on a crisp April morning, led by the Coldstream Guards band, the detachment marched at a quick pace to Waterloo Station, observed along the two-mile route by an interested crowd of Londoners.

Aldershot is about 30 miles west of London, in Hampshire, and here the detachment settled into barracks without incident, attached to the 6th Dragoon Guards. From Shornecliffe, fresh from the 15th Hussars who were off to India, came the horses: good, with plenty of bone, the majority being Irish mares. "Always full of beans, most of them accurate and continuous kickers in the stalls," records Trooper Vernon, "they derived their health from three groomings and three feeds a day, and plenty of steady exercise." Their new riders had difficulty in teaching them to canter, this pace being unusual in enclosed countries, but they found that the mares trotted fast and steadily for long distances, the 6 m.p.h. laid down for long rides being no trouble to them. "The paces a regiment teaches its horses," remarks Colonel Vernon, "should be guided by the work to be done, and the class of country. But after two and a half years of responsibility in France, I advocate for Australia the trot only on roads and the slow canter on soft ground into which a regularly trained horse soon breaks of his own custom." The cavalry had to relearn its paces in Africa, many regiments taking too long to realise the Boers were beating them in horsemanship all the time. The wafer from Australia had the natural paces for the veldt and thrived better on the Karoo bushes than the Irish horse.

For the first three weeks at Aldershot, riding school chief mounted feature of the training schedule. This included some days on hills specially planted with prickly gorse, with stirrups crossed over on the wallets of the well-polished saddles.

Generally the horses were led out at 5.15 a.m. stables parade, one man, riding on numnah and surcingle, to four horses. The Australians found the 6th Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers), of whom they formed the fourth squadron, great adepts at long trots, managing the pullets like trick riders, and at this phase of cavalry work as good as any. Trained jumping was fine, and the care taken of each horse, reckoned worth £30 each, was thoroughly enforced to the great advantage of the corps.

As part of Brigadier-General French's Brigade, viz 6th D.G. (Colonel Porter) , 12th Lancers (Earl of Airlie) and 13th Hussars, the detachment soon settled down to strenuous training. The hard continual practice in sword and lance exercises developed the men rapidly, and, at the end, the average height of the squadron was close to six feet. To this practice was added a short course of musketry. Of this the cavalry seemed to get very little, the result being most noticeable next year in Africa.

"There were daily drills in the Long Valley," writes the trooper. "A stretch of some miles of grassless plain, inches deep in dust at times. For the first few weeks, during which many of the squadron were in hospital from colds which I put down to the thin `blues', the horse lines were on the edge of the valley, and our quarters in Badajos Barracks with first the 2nd Devons and then the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers ('Fighting Fifth'), just back from Egypt and Crete. When we came in from drill covered in the dust and indistinguishable, the barracks rule was to cut off the water for fear washing would hurt the skin, while our objections were ignored.

"Many field days in the country-side took place late in summer; speed and shrewd use of the hills and valleys from the officers' down to troopers' patrols made us successful and respected. Our C.O., Colonel Porter, never got used to the cantering of horses, and occasionally stopped operations by trumpet calls, but there can be no doubt he must have reversed his opinion when he was our brigadier in the Free State and Transvaal. If only a trooper could sometimes discuss matters on equal terms with higher authority - so we think!"

During a spell of intensely cold weather, the Royal Military 'Tournament was held at the Agricultural Hall., Islington. Here, from May 25 to June 8 camels as well as horses had to be looked after, the former being required for the displays which were a feature of the proceedings. Twenty-six performances of a "Cavalry Display by 6th Dragoon Guards and N.S.W. Lancers" were given, the display representing an engagement between a band of Dervishes and a patrol of Carabiniers. After the initial encounter, the Dervishes scored a temporary victory by reason of their numbers. The reinforcement of the Carabiniers by a detachment of N.S.W. Lancers, however, led to the final defeat of the Dervishes by the combined Imperial Force.

The Islington Tournament was followed by the Royal Irish Military Tournament at Ball's Bridge, Dublin, June 14 to 21. Twenty-five members of the squadron, under Lieutenant Osborne, were boarded by Sergeant-Major Harry Read at Holyhead, at 4 a.m. By some unfortunate mistake, the detachment boarded the wrong ship. On arrival, they successfully bluffed their way out of this contretemps, only to be marched from the station behind a trumpeters' band of the 1st (King's) Dragoon Guards, who out of devilment set a pace of 5 m.p.h. on a short 24-inch stride!

Team events in which this detachment took part were: riding and jumping, cavalry lance-exercise, cavalry sword exercise and pursuing practice, wrestling on horseback. The competitors were usually 1st (King's) Dragoon Guards, 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons and 8th (King's Royal Irish) Hussars. There were also numerous entries in the individual events, and at the end of a fortnight the detachment returned with some, though not a large list of prizes.

Another team went to Aberdeen, Scotland. Though they certainly did not meet the crack regiments, the members of this team took almost every prize with ease, and were overwhelmed with hospitality and friendliness by both the Scottish soldiers and the people.

Apart from these breaks in the rigours of training, little time was allowed for amusement. There were, however, one or two memorable occasions, including a night at the Empire Theatre given by Lord Carrington to the Australian cricketers and the squadron; one at the Alhambra, three days before war was declared, when an actor in a N.S.W. Lancer uniform made "Soldiers of the Queen" the current popular song, and a visit to the stables and parks of Lord Rosebery, in Buckinghamshire. Here Corporal Gould got lost in the "Maze", his feathers marking his progress by appearing over the hedges, his comrades cheering until he found his way out!

In July the 6th Dragoon Guards left for three weeks' manoeuvres and the 7th Dragoon Guards (the Black Horse) took their place, with the N.S.W. Lancers as a squadron. The Lancers heard with interest that these two regiments had not been quartered together since the Peninsular War of 1809-19. Tradition forbade friendship, for on one occasion the 6th Dragoon Guards, getting a bad mauling, abandoned their baggage on the order "Threes about", and the 7th Dragoon Guards arrived fresh and retook it, whereupon the Iron Duke gave the red jackets of the Carabiniers to the Black Horse, the blue jackets of the Black Horse going to the 6th Dragoon Guards in exchange.

The passing through, one night, of the 10th Hussars provided the Australians with yet another glimpse of tradition. When the "Shining Tenth" marched into barracks, the Lancers "mucked them in", i.e., cleaned horse and saddlery and provided bowls of tea.

Perfect August weather found the squadron trucked to take part for three weeks in the annual Salisbury Plains manoeuvres. The men found the grassy chalk down ideal for field work and entered enthusiastically into a "two schemes each day" routine, which topped off their term of intensive training to perfection.

Return to barracks was accomplished in an atmosphere of considerable expectancy and suspense. As the friction with the Boers increased, Captain Cox became more active in trying to get official sanction from the War Office for acceptance in case of fighting. Though no promise was either asked or expected from the rank and file, only a sergeant refused, on principle, to extend the duration of the trip. But when the time came for the fortnight's leave before returning to New South Wales, nothing was definite, and five members of the squadron decided to hand in regimental property and set about their private business in London. The men were warned that their ship, the S.S. Nineveh, would sail on October 10. With dramatic coincidence, on October 9 the Boers crossed into the British territories of Cape Colony and Natal, and on the 11th, England declared war. Enthusiastic demonstrations from the Londoners and speeches from the Mansion. House marked the march of the N.S.W. Lancers through the chief streets of London to the deck. Delayed for a day by fog, the squadron eventually found itself at sea, a group of highly trained men, anxious to test their strength, chafing not a little under the uncertainties inevitable to their situation.

Meanwhile, at home, applications for enlistment in the Lancers poured in from all quarters. The establishment at May 1899 had been 27 officers and 401 other ranks, a total of 428, but some 2,000 more now wished to join. It was thought risky to make the regiment too unwieldy, but some increase was made; Sydney and Parramatta were each expanded to full squadron strength in 1900 and by the end of the year the establishment and strength were roughly:

Thirteen half-squadrons of 50 men each -

Sydney, 2;

Parramatta, 2;

Hunter River, 2;

Illawarra, 2;

Northern Rivers, 2;

Richmond, 1 (formed 1 October 1900);

Windsor, 1 (formed 1 October 1900);

Newcastle, 1 (formed 1 October 1900)

Total - 650 men

Regimental staff - 10 men

Band (Parramatta) - 25 men

Cadets (Parramatta) - 60 men

Drilled supernumeraries (unpaid) - 100 men

Grand Total - 845 men

Previous: New South Wales Lancers 1885 to 1897

Next: New South Wales Lancers, South African War

Further Reading:

1st/7th/1st (New South Wales Lancers) Australian Light Horse

New South Wales Lancers, Boer War Contingent

Militia Light Horse, New South Wales

Australian Militia Light Horse

Citation: New South Wales Lancers 1897 to 1900