Topic: BatzN - Cocos Is

Cocos Islands

Indian Ocean, 9 November 1914

Cocos Islands, the first engagement fought by a warship of the Royal Australian Navy, occurred on 9 November 1914 off this British-ruled group of 27 small coral islands situated in the Indian Ocean 2,800 kilometres north-west of Perth, Western Australia. The action came about after the light cruiser Emden (3,600 tonnes), a unit of the German Pacific Squadron then enjoying a highly successful career raiding Allied shipping, anchored off Direction Island early on 9 November and sent ashore 43 officers and men to destroy the vital radio and cable station there which connected the Australian, African and Indian telegraph systems. Before this aim could be achieved, the staff of the station managed to send off warning messages of the presence of a `strange warship'.

Unknown to the Emden's commander, Captain Karl von Müller, a convoy of 38 transports carrying the first contingents of Australian and New Zealand troops overseas was at that moment passing just 80 kilometres to the east, escorted by the Australian light cruisers Melbourne and Sydney (5,400 tonnes) and the powerful Japanese battle-cruiser Ibuki (10,000 tonnes). Until the previous day the convoy had been led by the British armoured cruiser Minotaur, but, after that vessel was called away to Mauritius, Melbourne (under Captain Mortimer Silver, RN) had taken over this role. On receipt of the signals from Corns, Silver's first instinct was to himself go and investigate. Appreciating his wider responsibility, however, at 7 a.m. he detached Sydney-which was, in any event, then posted on the convoy's port side nearest to the reported trouble. He had to restrain Ibuki's captain, Vice-Admiral Kato Kanji, who wished to accompany Sydney.

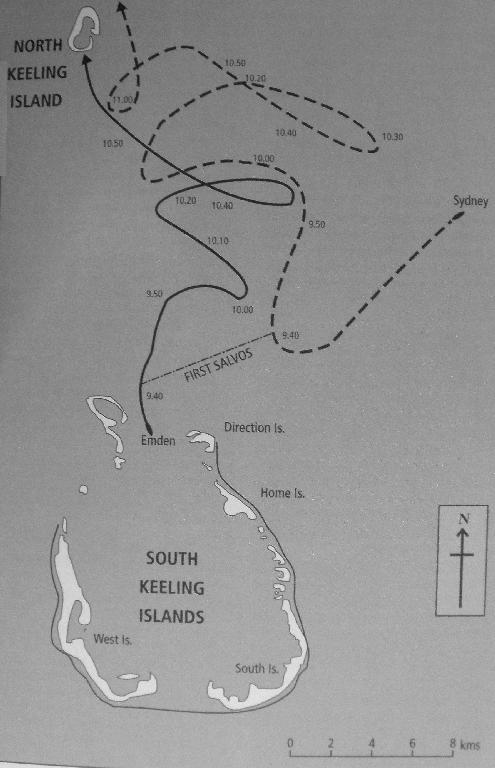

As Sydney steamed westward at 20 knots, her smoke was spotted on the horizon by Emden soon after 9 a.m. At first von Muffler thought this came from the collier, Buresk, which was supporting his operations, but less than fifteen minutes later he realised his mistake as what was plainly a British cruiser bore down on him from the north-east. Without waiting to collect the landing party ashore, he moved out to sea to gain room to manoeuvre and prepared for combat. On identifying the class of the enemy ship he had discovered, the commander of Sydney (Captain John Glossop, RN) consulted standard references on board and decided to close to 9,500 yards (8.7 kilometres) before engaging. lie believed that this would place him just outside the range of his opponent's 4.1 inch guns while bringing Emden fully under the fire of his own 6-inch armament. Unknown to him, however, was the fact that the mountings of the German's guns had undergone elevation modifications which increased their range.

No sooner had Glossop closed to 10,500 yards (9.6 kilometres) and swung onto a parallel course at 9.-10 a.m. than Emden opened fire at extreme range. The five shells of this first salvo passed over the top of Sydney but still splashed down within 200 metres of their target, and a hail of further rounds quickly followed. Von Müller had ordered rapid fire so that Emden was reportedly sending off a salvo every six seconds. At least fifteen shells thus found their mark on Sydney-al though fortunately no more than five of these actually exploded. All the Australian cruiser's casualties of four men killed and twelve wounded occurred during these first ten minutes of the action, before Glossop moved back out beyond his opponent's reach.

Initially hampered in returning effective fire through having both range-finders put out of action, Glossop used his superior speed of 27 knots (compared with Emden's seventeen) to thwart any attempt to get close enough to torpedo him. Once Sydney's shells began to find their mark, moreover, their effect was decisive, since each 6-inch shell weighed 45 kg (compared with the 17 kg of Emden's shells) and Sydney eventually succeeded in landing about 100 of these hammer blows upon her lighter adversary. Soon the German vessel was totally wrecked, with its hull holed at numerous points, its superstructure a blazing shambles, half the crew disabled, and steering only possible using the screws. But the Emden continued to fight, with at least one gun still firing at 11 a.m.

Realising the hopelessness of his position, von Müller chose to run his ship onto the reef at North Keeling Island to prevent it sinking with so many wounded on hoard. Once Emden was aground by 11.15 a.m., Glossop decided to go after the enemy's supply ship, Buresk, which had been hovering on the edge of the action apparently looking for an opportunity to ram him. When the collier was eventually overtaken shortly after noon, a prize crew put on hoard discovered that the German crew had already taken measures to sink the ship and it was beyond saving.

On returning to Emden's shattered remains at 4 p.m., Glossop found the enemy ship still flying its battle ensign. After demands to surrender were ignored, he considered that von Müller was declaring an intention to continue resistance by whatever means was still open to him; he accordingly ordered a further two salvos fired into the wreck. Only then was the white flag raised and the German colours hauled down. There was later some criticism of Glossop's action at this point, which inevitably caused needless casualties, but there was no doubting that he behaved correctly according to the usages of naval warfare.

Even now, Sydney was unable to move directly to the aid of Emden's surviving crew, since there was still the group of Germans ashore on Direction Island to be dealt with. It was subsequently discovered that this party had commandeered a schooner during the action and managed to sail away in the dusk; after an adventurous journey, they managed to reach Arabia and eventually made their way back to Germany. Not until late on 10 November was Sydney finally able to render medical assistance to the 190 of Emden's officers and men who had survived the fight. 65 of whom were wounded; eight officers and 126 other ranks had been killed, twenty of them during the final two salvos. After transhipping the survivors into Sydney, Glossop made for Colombo to rejoin the convoy.

Despite the immense and widespread jubilation at news of Emden's destruction, and especially the fact that this had been achieved by a warship of Australia's new navy it had been a markedly one-sided contest. Interviewed shortly after the action, Glossop expressed his horror at what he saw of the effects of his fire on his opponent, declaring

My God, what a sight! Her captain had been out of action ten minutes after the fight started from lydite fumes, and everybody on hoard was demented ... by shock, and fumes, and the roar of shells bursting among them. She was a shambles. Blood, guts, flesh, and uniforms were all scattered about. One of our shells had landed behind a gun shield, and had blown the whole gun-crew into one pulp. You couldn't even tell how many men there had been. They must have had forte minutes of hell on that ship.... and the survivors were practically madmen.

In reality, Emden's fate at Sydney's hands was almost comparable to that which befell HMAS Yarra in a clash with Japanese cruisers 28 years later (see South of Java).

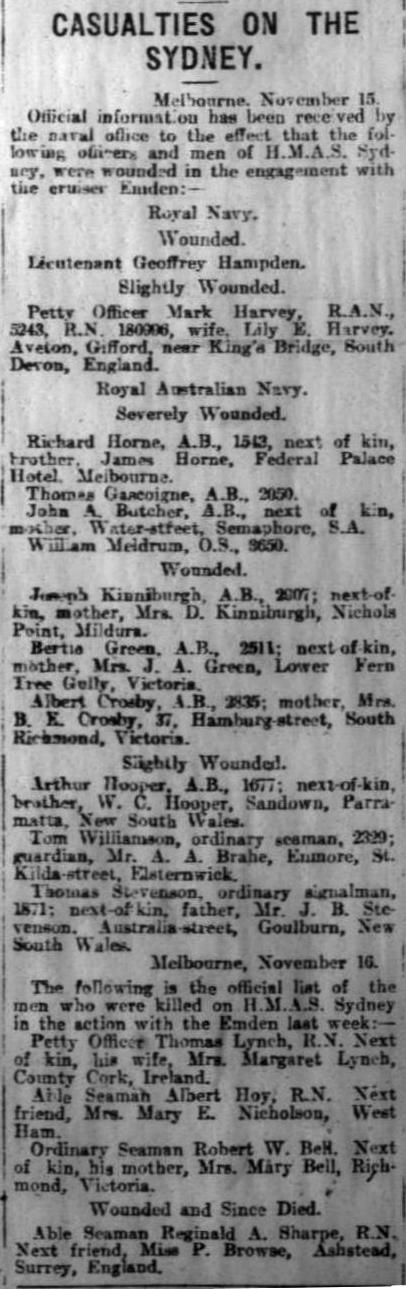

The Casualty List

The details of casualties from the HMAS Sydney

[From: Adelaide Chronicle, 21 November 1914, p. 42.]

One of the severely wounded, James Arthur Butcher.

20 year old James Arthur Butcher who was severely wounded on the HMAS Sydney was born at Birkenhead, South Australia. He was the son of Captain Butcher, master of the coastal ship Echunga. His brother, William Butcher was the master of a trading boat in the Solomon Islands. James Butcher joined the Royal Navy and first sailed in the HMS Drake but transferred to the HMAS Sydney in February, 1914.

[From: Adelaide Chronicle, 21 November 1914, p. 45.]

Extracted from the book produced by Chris Coulthard-Clark, Where Australians Fought - The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1998, pp. 97-100.

Additional References cited by Chris Coulthard-Clark:

Arthur W. Jose, (1928), The Royal Australian Navy, 1914-1918, Sydney Angus & Robertson.

A. B. Paterson, (1934), Happy Dispatches, Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Further Reading:

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: Cocos Islands, Indian Ocean, November 9, 1914