The following account is extracted from H.S. Gullett, (1944),

, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, pp. 435 - 444.

Between Sheria and Khuweilfe on the morning of the 7th the line of the Turks was weak While the 60th Division was to carry the high ground north of Tel el Sheria, and allow the Australian Mounted Division to pass through, Chaytor was to drive through the opposition towards the north-west, seize the enemy's ammunition dump on the railway at Ameidat, and then with the Australian Mounted Division ride north-west with all speed across the enemy's communications. Cox with the 1st Brigade was to have moved in the lead at 5 a.m.; but owing to bad roads the batteries had been unable to reach the point of concentration in the darkness, and it was nearly 6.30 before the brigade was on the march. By 7.15 Cox had reached a position on the Wadi Sheria just east of Khurbet Urn el Bakr. Riding briskly with the 2nd Brigade in support, the advance-guard of the 1st was within striking distance of Ameidat at 10.45. Cox's regiments, as they travelled, had been constantly, though not heavily, shelled from the east and the north-west, but so far there was no serious opposition.

When the brigade was within three miles of Ameidat, the 2nd Regiment on the left was in touch with the extreme right of the troops of the 60th Division who were held up north of Tel el Sheria. The 1st and 3rd Regiments were echeloned on the right. The country was clear, and the going good Passing the infantry, and with their left flank now exposed, the squadrons of the 2nd increased the pace to the gallop, and swooped with loud shouts on Ameidat. Except for shell-fire at long ranges there was little resistance, and in a few minutes the light horsemen had dashed past the railway station, and were rounding up startled Turks who were surrendering readily on all sides. Thirty-one officers and 360 other ranks were made prisoner; and the captures included 250 shells, 200,000 rounds of small arms ammunition, 27 ammunition wagons, a complete field hospital, and a great quantity of stores.

The enemy gunners at once began to shell the dumps, and Cox pushed out reconnaissance squadrons to Tel en Nejile and Khurbet Jemmameh. A line running eastwards from Tel Abu Dilakh was found to be held in strength; as this barred the advance to Huj. Persistent attempts were made during the afternoon to shift the enemy from the village of Dilakh. At 12.30 Chauvel informed Chaytor that Gaza had fallen, and ordered him to advance at once on Jemmameh, towards which large bodies of Turks were reported to be retreating. Cox's attack on Dilakh however, could make but little headway. The village was placed on a commanding knoll; the enemy, alive to the menace to his rear, was bringing up reinforcements. and opened on the Australians with a battery from a point north of the village. Chaytor therefore decided to attack it with the 2nd Brigade.

The 5th Regiment, with about one and a half miles to cover, moved on Dilakh at the gallop. The Turks greeted this advance with salvoes of shrapnel and high explosive, and the light horse were at once enshrouded in clouds of dust and smoke from the shells. Cameron's men gained part of the high ground near Dilakh, but found that the guns were firing from a village beyond. Unable to advance further in the failing light, they established a line and held on during the night. Casualties in the regiment had been light, but Lieutenant C. R. Morley was mortally wounded in the charge. At dawn on the 8th the regiment carried the position and rode against the guns to the north-west. Already the Turks were evacuating their positions, and Captain J. McC. Boyd with the advanced squadron, had a hard gallop after two guns which were being hurried towards the Wadi Hesi. Fine dash was shown by the leading troop-leader, Lieutenant E. G. 0gg, and the guns and their teams and escort were secured.

All through the afternoon of the 7th Chaytor had looked out anxiously but vainly for Hodgson's brigades. He fully recognised that the opportunity which offered for a blow at the enemy's line of retreat was each hour slipping away. But he was powerless. At 4.30 all his troops, with the exception of two squadrons of the 1st Brigade, were in the firing line. His horses had not been watered since leaving Beersheba, and many of them had missed the drink there. A few squadrons found water during the day, but some regiments were already threatened with prostration. He therefore decided to abandon for the day the attempt to reach Jemmameh, and to rest on his ground, watering as many horses as possible during the night.

That night Cameron, of the 12th Regiment, was ordered to proceed at dawn to make touch with the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade at Beit Hanun. This brigade, after moving through Gaza, was on the left of the Turks from the Atawineh part of the old line, who were heading for Huj and the north. Cameron, trotting with his men immediately in rear of the retreating enemy, carried orders to the brigadier to endeavour to cut across the head of the Turkish columns and make Huj. where he would be joined by the 60th and Australian Mounted Divisions. The 12th covered the ten and a half miles in an hour and a half; but before Cameron reached the Imperial Service Brigade the Turks were already streaming past Huj, and 110 action could be taken. Cameron afterwards rejoined his division at Huj.

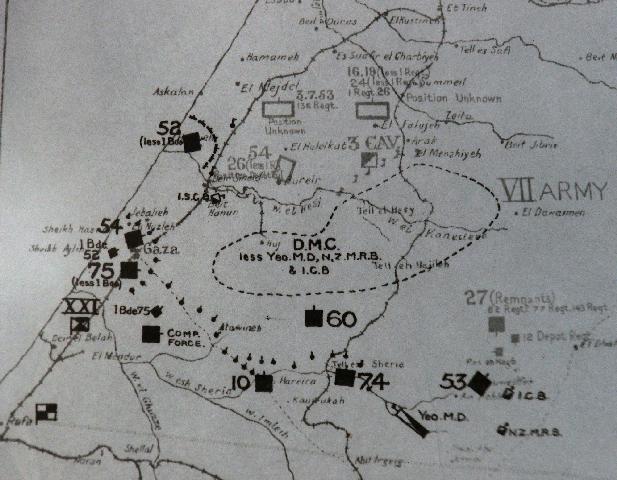

On the 8th the Anzac Mounted Division was ordered by Chauvel to strike for Jemmameh and the 60th Division for Huj, with the Australian Mounted Division advancing in the gap between them. The 52nd Division, with the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade, was to advance as rapidly as possible up the coast, and it was hoped that even yet the gap between Chauvel's horsemen and the advanced infantry along the seaboard might be closed in time to cut off the escape of large enemy forces. If in the opening days of the battle the General Staff of the Turkish army had made blunders, it now had a sound grip of the situation. The enemy, by holding up Chauvel's advance from the south-east towards Huj, until his main force had retreated past that place, had saved his army from destruction. With his flanks now secure from the British cavalry, he would be able to offer stout rear-guard resistance.

The 10th Division marched finely throughout the day of the 8th, with the Australian Mounted Division on its right. The resistance of the Turks, although broken, was persistent, and three times their rear-guard held up the Londoners. Further west the 75th Infantry Division occupied Tank Redoubt, Atawineh, and other trench systems with but slight opposition. On the extreme left the Lowlanders of the 52nd Division seized high ground north-west of Deir Sineid. Four times during the day the Scots were driven off this position by greatly superior Turkish forces which advanced from Askalon; but each time they returned to the charge, and on the fifth occasion cleared the ground with the bayonet and held it.

Unfortunately, on this day of great possibilities for the mounted troops, the Yeomanry Division, which was still quite fresh, the New Zealand Brigade, and the Camel Brigade were all still on the extreme right flank.

Circumstances, as we have seen, had broken up Desert Mounted Corps at the critical moment. With orders to move first on Jemmameh and thence towards Burier, Chaytor, with Anzac Mounted Division, pushed out a reconnaissance at dawn. Early in the morning the 2nd Brigade on the right occupied the line Tel em Nejile Wadi Hesi. Considerable shelling and general opposition made progress slow, and an hour later the 7th Mounted Brigade, which had been sent to reinforce Chaytor, was ordered in between the two light horse brigades. As Chaytor's men went forward, the evil consequences of the day's delay at Sheria were strikingly disclosed to them. From each successive ridge they saw the wide plain extending towards the coastal sand-dunes, and on it column after column of the Turkish army hurrying to the north. But so far the enemy was safe. As the excited Australians and yeomanry observed what might have been the realisation of every cavalryman's dream-as each regimental or squadron leader instinctively pulled himself together for the charge-they were reminded by resistance immediately ahead that in the past twenty-four hours the enemy had been enabled to protect his flank against their galloping sweep. The 5th Light Horse Regiment was scarcely clear of the Dilakh position before it was vigorously attacked by enemy infantry and compelled to withdraw its advance-guards. A similar check was imposed on the squadrons of the 6th. Finding good cover in the wadis and rough ground in front of Jemmameh, the Turks were offering resistance strong enough to serve their purpose. For a time the 7th Mounted Brigade in the centre had a clear advance; but soon after noon the British also were arrested, and then subjected to a solid counter-attack which continued for more than three hours. The yeomanry, who stood firm and shot down large numbers of the advancing infantry, were relieved when the 1st Light Horse Brigade took Jemmameh.

Cox's men, fighting for Jemmameh, made a slow dismounted attack, and it was not until after 3 o'clock that troops of the 3rd Regiment entered the village, having in the final assault been pushed through the advanced line of the 2nd. In itself the village was important, for in addition to 200 prisoners the captures included a considerable reservoir with its pumping plant, two howitzers, two machine-guns, and a quantity of other important material. But in view of the delay, these trophies were of little consequence. The 2nd Light Horse Regiment at once resumed the advance, but was again held up on ridges west of Jemmameh, and Cox's headquarters were still in the village at nightfall.' As the division advanced on Jemmameh, touch had been gained with the Australian Mounted Division on the left, and the 10th Light Horse Regiment on Hodgson's right flank had cooperated in the earlier stages of the attack on the village.

The Anzac line was then advanced to cover the water at Jemmameh and Nejile, and the Turks again countered in strength against the 5th and 7th Light Horse Regiments. From 3,000 to 5,000 infantry, supported by a number of guns, advanced with the bayonet to drive Chaytor's men back from the water. Had this attempt been successful, their retreat would have been assured. But, although the Australians had only about 500 men in the firing line, they occupied good ground, and, as one of their leaders said, "they never shot so calmly and surely in their lives." In places Turks came within forty yards of the slender line, but the main body was held at about 700 yards. The fight fizzled out at dark; and during the night the enemy, recognising that these swift riding, straight-shooting horsemen, refreshed by the water, would become very active and dangerous again in the morning, withdrew for some miles. Turkish casualties were heavy; one shallow trench contained twenty-one dead, all shot through the head-a fact which demonstrated the quality of the Australian work with the rifle.

It was now imperative that Chaytor should at once water the horses of his two Australian brigades. With few exceptions all the animals had been without a drink for fifty hours, and some longer. All that time they had been ridden hard under their twenty-stone burdens, and for more than twenty-four hours, in consequence of their extreme thirst, had refused to eat their scanty ration of grain. But despite their distress they were, on the evening of the 8th, still gamely answering every call.

The plight of the men was scarcely better.

They had been sustained by a short ration of water; but they had now been for three days and nights without sleep, and constantly in the saddle or fighting on foot. That night, therefore, the horses were fully watered at Jemmameh and Nejile many as possible twice-and the men, if they got little or no rest, were happy in the relief of their treasured chargers. The affection of the light horseman for his horse was always demonstrated in these seasons of trial, and it was not uncommon to see a man pour out the slender contents of his own water-bottle on his hand or a tin plate, to wet the parched mouth of his waler.

While the Anzac Mounted Division had to be content with the capture of Jemmameh, better fortune attended Hodgson's Australian Division, which advanced with the 60th Division on Huj. On the night of the 7th, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade under Wilson was ordered at all costs to occupy the line Wadi Jemmameh-Zuheilkah at dawn on the 8th; thus Wilson would have the 5th Mounted Brigade on his left, and was to make touch with the Anzacs on his right. The 3rd and the yeomanry were then to march on Huj, covering the right flank of the 60th Division. Moving before dawn, the 9th and 10th Regiments of Wilson's brigade met with stiff opposition as the day disclosed them to the enemy. The Turks occupied favourable ground with scattered entrenchments, and were only dislodged after a spirited dismounted attack by the Australians, who were supported by good shooting at close ranges by the Notts Battery. By 10 o’clock the 5th Mounted Brigade was in touch on the left, and the enemy was being driven in large numbers and at a smart pace towards Huj.

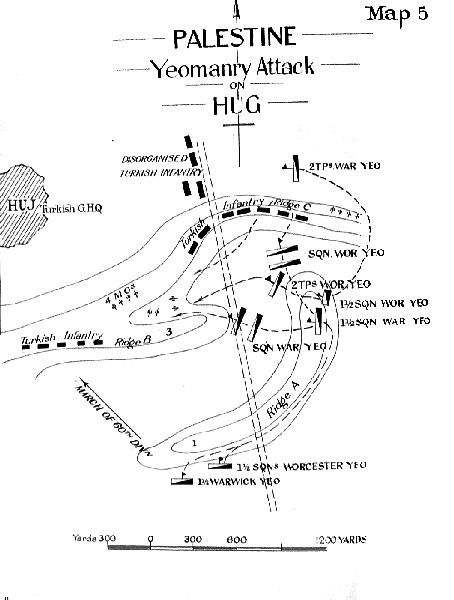

At the same time the Londoners of the 60th were swinging forward grandly on the left, beating down a strong Turkish rear-guard in their stride. The spirit and endurance of the division shone out even at this time, when all Allenby's infantry was behaving superbly. They had now been fighting and marching hard for nine days, but their advance across the broken country to Huj was distinguished by the enthusiasm and vigour of perfectly fresh troops. General Shea, a dashing personal leader of men, was travelling with the first waves in a motor-car lent to him by Chauvel, and, picking his way across the many wadis, was doing his own reconnaissance and directing the advance. When within two or three miles of Huj, he observed a strong column of Turks passing across his front a mile and a half away. Between the Londoners and the column lay a stretch of rough, difficult country, and the enemy, observing his advantage, halted and brought a number of guns into action. But about a mile away to the right Shea saw some troops of the 5th Mounted Brigade pressing forward; driving across, he pointed out the Turkish force to Lieutenant-Colonel Gray-Cheape (who commanded the Warwicks) and asked for his assistance.

Cheape had only ten troops of the Warwicks and Worcesters-about 200 men-but he decided instantly to charge. Rapidly forming his men, he led them at the gallop upon the Turks, riding direct for the guns. The yeomanry had about a mile and a half to go, first down a slope in full view of the gunners, and then across an exposed valley. As the British spurred down the slope, the Turkish guns lifted their fire from the British infantry, and concentrated on the approaching horsemen. Serving their guns rapidly, the artillerymen constantly shortened the range, until, as the shouting yeomanry dashed sword in hand up to the batteries, shells were bursting and scattering widely as they left the muzzles. And while they were ploughed by the shells. the horsemen also rode through a whirl of machinegun fire. But they spurred right home, sabred the gunners as they served their pieces, and then, re-forming under Cheape, dashed at a nest of machine-guns and killed the crews. In this fine gallop the yeomanry lost heavily; but they were well rewarded for their sacrifice, capturing 11 guns, 3 machineguns, and 30 prisoners. This splendid exploit enabled the Londoners to continue their rapid advance in comparative safety, and permitted the 3rd Light Horse Brigade a little later to enter the village of Huj. Moreover it decisively smashed the Turkish rear-guard, and not until the enemy reached the Wadi Sukereir was he able again to offer stiff resistance.

As the yeomanry charged, they were in full view of the Australians on their right. Earlier in the campaign, when the men of the 5th Brigade were raw and indifferently led, their performance was at times not impressive. But at Huj they showed the traditional mettle of their famous old stock, from which most of the light horsemen were themselves descended; and the Australians were quick to appreciate the fact that British Territorial horsemen must no longer be estimated lightly as campaigners. The charge, coming after the brilliant light horse success at Beersheba, was a severe blow to the already diminished Turkish spirit, and the news of it, ringing through Chauvel's mounted troops, made all the horsemen and their leaders still more scornful of Turkish resistance if resolutely galloped.

If the main Turkish army had escaped destruction, its condition was serious. From Gaza and the defences to the west of the town the race for safety had been a grim one. All arms were exhausted by the severe bombardment and fighting before they were withdrawn from their trenches. Their communications had been for some days disorganised; their supplies had run short; the troops were hungry and thirsty; and the army, as is common with troops in such circumstances, was sorely afflicted with dysentery. Discipline had gone to the winds; ranks were broken; unit mingled with unit, service with service. Only one motive animated and directed the force and saved it from destruction. Every man knew that safety lay to the north, an:! all remaining effort in each wretchedly exhausted body was whipped up to conform to the orders of the High Command.

Had Allenby's original plan succeeded-had Chetwode's advance to Sheria been possible on the 4th instead of on the 6th-had Huj, even after the delay, been reached by the 60th Division and the mounted troops on the 7th-the destruction or capture of the bulk of the Turkish army would have been assured. The Commander-in-Chief's foresight and preparations had achieved a great victory, and was only denied its full fruits by two factors beyond his control-the resistance at Khuweilfe, and the absence of water after Beersheba was taken.

H.S. Gullett, (1944), The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, Sydney: Angus & Robertson.