Topic: Militia - LHQ - Qld

Queensland Mounted Infantry

Outline, Part 2

Forward

March: Soldiers of the Queen

Allied with: King Edward's Horse (The King's Oversea Dominions Regiment).

The following outline of the Queensland Mounted Infantry is extracted from a book written by Joan Starr called Forward: the history of the 2nd / 14th Light Horse (Queensland Mounted Infantry), published Queensland, 1989. This section comes from pp. 4 - 9:

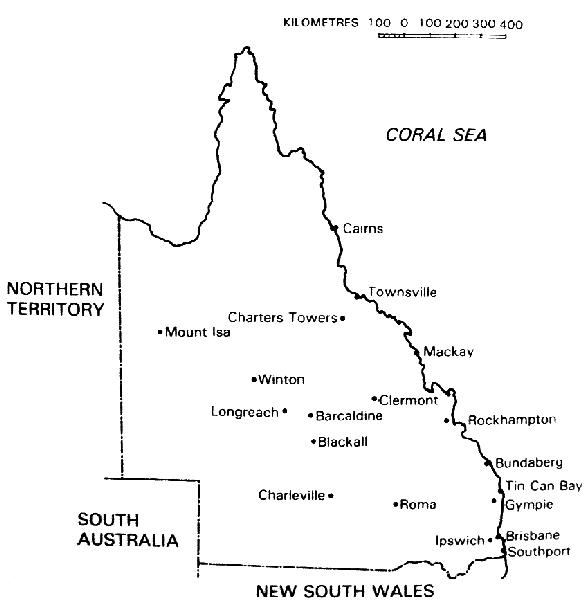

Towns in Queensland affected by the Shearers' Strike, 1890.

The Shearers' Strike

The first "action" for the Queensland Defence Force occurred in 1891 in the Western District of the Colony in what was to become known as the "Shearers' Strike". The confrontation began in the late 1880s when leading pastoralists, feeling the pinch of lower wool prices announced they would reduce the pay of the shearers. The shearers were already seething at their unjust conditions, they were paid as low as eight shillings per hundred sheep and then had to pay unusually high prices for the goods provided by the squatters, often leaving the shearers as little as fifteen shillings per week. For this they worked eleven hours per day and were accommodated in the roughest of conditions - earth-floored huts without ventilation or lights. They could not quit for fear of forfeiting accumulated pay, but the squatter on the other hand could withhold payment if he considered a sheep not properly shorn, and he could dismiss a worker without reason and not pay a penny for work already completed. To counter these unfair conditions, the shearers formed unions and between 1886-89 staged more than three hundred minor strikes and walk outs.

In 1890, the Queensland Shearers' Union was strong enough for a full-scale showdown. The crisis came to a head when the union demanded that only union labour be used in the sheds. Initially the pastoralists refused, but they backed down when wharf labourers refused to handle wool shorn by non-unionists. However, in late 1890, the pastoralists held a conference in Melbourne where they decided to levy members in proportion to the number of sheep to create a fighting fund to defeat the shearers. The squatters were preparing to fight the shearers once again and they nominated Queensland as the battlefield.

The 1891 season was off to a fiery start when the squatters refused to observe the closed shop principle they had conceded the previous year. Union passions were further inflamed by reports that under a new agreement shearer's pay would be slashed thirteen to thirty-three per cent, and penalty clauses decreed that defiant shearers could be fined or jailed. Union representatives tried to negotiate, but the squatters declared that they would only employ on their terms. Thus rebuffed, hundreds of Queensland shearers walked out of the shearing sheds. With their wives and children they gathered in a dozen strike camps and prepared to battle the thousand strike breakers imported from New South Wales and Victoria. In early February 1891, the first of the contracted labourers arrived in Rockhampton from the southern states and were quickly despatched to properties in the Western Districts. Violence flared as strikers clashed with strike breakers, wool and storage sheds went up in flames on properties where "black" labour was employed.

Large camps were established by the unionists at Barcaldine 6 Forward

(1,000 men), two near Clermont (350 and 150 men), and Capella (80 men). Inflammatory speeches were made with threats of kidnapping squatters and their families, and burning properties. At this juncture the Queensland government ordered additional police to the troubled areas and police magistrates were instructed to enrol all available men as special constables. There was a fear that the trouble could spread and erupt into civil war.

By 20 February the situation had reached such a serious stage that the government decided to call out the Defence Force in aid of the civil power. That morning the Officer Commanding the Defence Force, Major Jackson, was warned to prepare for immediate embarkation. At 5.00 p.m., a force of sixty-one men complete with weapons, a machine-gun and a 9 pounder field gun, sailed for Rockhampton. Three hours later orders were issued to call out the Moreton Mounted Infantry. The Commanding Officer, Major Percy Ricardo, took immediate steps to secure the attendance of all members of the units resulting in four officers and fifty-five men being selected for active duty.

They embarked on the SS Wondonga and sailed for Rockhampton the following day. No horses were despatched as the Pastoralists' Association had arranged to provide mounts, but every member took his own saddle and bridle in addition to kit, accoutrements and ammunition. That same day, 21 February, the Rockhampton Mounted Infantry was called out by the local Police Magistrate. On arrival at Rockhampton the entire force came under the command of Major Jackson. The force travelled by train to Clermont and thence despatched to farms to protect the free labourers and property.

As the situation continued to deteriorate the government called out additional volunteer units including the Wide Bay Mounted Infantry, Mackay Mounted Infantry, Darling Downs Mounted Infantry, Charters Towers Mounted Infantry, and Townsville Mounted Infantry, in addition to units of the Defence Force. The task of aid to the civil power is one that most soldiers dislike. It was work that neither commanders nor men had been trained for and which demanded a level of discipline to be found only among the regulars. Nevertheless the men performed the duty admirably as evidenced by Lieutenant Harry Chauvel's action at Charleville.

Chauvel received a warning order on 24 March to be ready to move to Charleville with twenty men and their horses. The men of the Darling Downs Mounted Infantry were issued with fifty rounds of ammunition each, and were on their way by rail the following morning. By this time there were reports of the burning of pasture and fences by the unionists, while at Blackall a non-unionist's bullocks had been shot.

Chauvel was sent to escort a party of free labourers through the bush to a property north of Charleville. A few police were added to his command. It was a miserable journey across black soil in pouring rain so that after twenty miles the men and horses were exhausted. When barely a mile from their destination, the party ran into a crowd of about two hundred shearers streaming down the track. Several of them were wanted by the police and the inspector in charge quickly arrested four of them.

The shearers closed around the party, some waving iron bars and clubs, shouting in their excitement. One of the four men arrested began inciting the shearers and the situation became dangerous. Chauvel gave the order to load; the inspector told him to force his way through the crowd with his troops and free labourers. The raised rifles of the Mounted Infantry had a cooling effect on the tempers as they shepherded the non-unionists and four prisoners along the road. The inspector thwarted an attempt by the angry shearers to follow up and Chauvel reached Oakwood where another detachment of Mounted Infantry was waiting; these set off after the shearers and more arrests were made. Although minor, the incident impressed on Chauvel the power of discipline and the importance of a cool head in a crisis. Had he not kept his Mounted Infantry under strict control, and they were after all mainly station hands with little military training, there may have been a tragedy.

The Mounted Infantry units were employed principally on patrol and escort duty and to keep communications open between detachments, the police and headquarters. Strong detachments were posted at stations where free labourers were shearing and small detachments were posted as sentries at woolsheds and station buildings. The infantry and artillery were responsible for the security of public buildings, jails, railway stations, and goods sheds.

The tension reached its peak when 200 troops swooped on the strike committee's headquarters at Barcaldine and arrested twelve of the leaders, charging them with conspiracy. The strikers were outraged, some men calling for revolution. At Gympie soldiers fixed bayonets to disperse a menacing crowd, while at Rockhampton 200 strikers heckled police guarding the twelve arrested at Barcaldine, when they came to trial. During the trial, the judge Mr Justice Harding was scarcely impartial, stating that he would have shot the strikers if he had been one of the police. He sentenced the twelve including George Taylor and William Hamilton, who later became members of the Queensland Parliament, to three years hard labour each. These severe sentences provoked another outburst of violence.

Although the strikers voted to stay out on strike, signs of weakness began to appear. The first crack came when threats of long-term sanctions by the squatters forced wool carriers back to work. They really had no alternative, for with whole families subsisting on ten shillings a week, men, women and children were on the verge of starvation. Furthermore, rain had turned the strikers' camps into quagmires of stinking mud. On 11 June 1891, union leaders announced that the strike fund was exhausted. The strike was over. Although the shearers had lost their fight, many claimed that in the long term it had led to victory, as the bitter defeat convinced the unions of a need for a political Labor Party to fight their cause in Parliament.

The strike had proven to be an expensive affair, costing the government £170,000, the pastoralists £41,000 and the unions £60,000, huge sums in 1891.

At times the work of the Defence Forces had been arduous, each district being in a state of flood for a considerable period. Colonel French noted:

Long and trying marches, by day and night, over boggy country (swimming rivers several times a day), were constantly made by the Mounted Infantry, notably so by a detachment of the Moreton Mounted Infantry, under Lieutenant R.S. Browne, which marched 109 miles in thirty-two hours, and by a detachment of Darling Downs Mounted Infantry, under Captain King, which marched sixty-five miles in one day on grass-fed horses.

Colonel Drury reported,

"The general conduct of the troops called out has been reported by all Commanding Officers to have been good.... To the discretion and judgment shown by officers in command, and the patience exhibited by all ranks under provocation and insult, must be credited the fact that bloodshed, or injury to life or limb, has been happily obviated".

As the strike wore on, the men were out on patrol for about five months, and for most of their service endured the boredom that is so often the lot of soldiers. On the plains of Western Queensland emu were plentiful and the men could not resist the excitement of riding after a quarry that could give them a chase at speed. Emu feathers, tucked into the men's felt hats began to appear and soon became widespread among the soldiers. Bill Lieshman of the Gympie Mounted Rifles claimed to be with the group who started the practice. Writing many years later Bill said:

I was in a patrol under Lieutenant Vivian Tozer of the Gympie Mounted Infantry, at Coreena Woolshed. On the way we met another Gympie Mounted Infantry patrol under Captain W. Shanahan and they were chasing an emu, which came toward us. When it was shot, some of us dismounted and Terry Rogers and myself were the first to pull the tail feathers out and place them in our hats. Then all in the patrols got the feathers and placed them in their hats.

When they returned home the Queensland Government allowed the Mounted Infantry to wear the emu plume in recognition of its service during the strike. At first it was solely a Queensland decoration, but in 1903 the privilege was extended to Tasmanian and South Australian regiments and finally, in 1915, to all regiments of the Light Horse.

Previous: Queensland Mounted Infantry, Outline, Part 1

Next: Queensland Mounted Infantry, Outline, Part 3

Further Reading:

Boer War - Queensland Mounted Infantry

Australian Militia Light Horse

Citation: Queensland Mounted Infantry, Outline, Part 2