Topic: BatzG - Nek

The Nek

Gallipoli, 7 August 1915

Bean's Account

The following is an extract from Bean, CEW, The Story of Anzac: from 4 May, 1915 to the evacuation, (11th edition, 1941), pp. 607-624.

CHAPTER XXI

THE FEINTS OF AUGUST 7TH

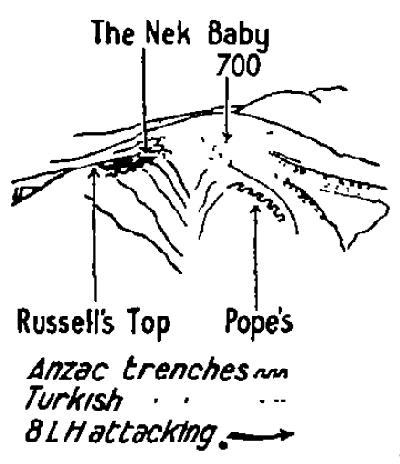

The actual storming of the Turkish trenches on The Nek and on Baby 700 beyond it was to be made by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade. Simultaneously the 1st Light Horse Brigade, then holding Pope's and Quinn's, was to seize with its 1st Regiment a part of the Chessboard and with its 2nd a sector of the Turkish Quinn's. Of these attacks, all difficult operations, that upon Baby 700 was by far the most important. The troops from Russell's Top were to be launched over the narrowing Nek to capture, first the several enemy trenches defending it, and immediately afterwards the maze of saps, about sixty in all, which seamed the front and both sides of the hill. If all the Turkish trenches were manned, the task would be absurdly beyond the power of the troops. But the light horse staff did not expect that any but the foremost Turkish lines would be occupied heavily, if at all, and the gigantic task was therefore confidently dealt with in the orders issued by the brigadier. Since the hillcrest along which the lines must first charge was a narrowing one between steep gullies, the number of men in each line was limited to 150. Two regiments of the 3rd Brigade, the 8th (Victoria) and 10th (Western Australia) were to undertake the main task, four lines, two from each regiment, following one another in quick succession The first line was to seize the Turkish trenches on The Nek, the second was to pass over them and take the nearer saps on Baby 700; the third would capture the farther trenches; the fourth, coming up with picks and shovels, would either fight or dig as required. The 8th Cheshire would then come over The Nek and help to consolidate; and, when once the trenches on The Nek had been secured, two companies of the 8th Royal Welch Fusiliers would climb up the western branch of Monash Valley, and from its head attack the nearer Turkish positions of the Chessboard, thus guarding the flank of the troops charging over The Nek, and eventually connecting with the assault of the 1st Regiment from Pope's. The troops were warned in orders that the garrison maintained by the enemy in his trenches appeared of late to be "not light," that machine-guns were believed to exist in five positions, all commanding the approach to The Nek, and that the fighting might disclose others. The five suspected gun-positions were widely scattered, and, with the exception of one, were all 200 yards or more beyond the Turkish front. They could not therefore be seized and silenced at the first rush; but it was stated in the light horse orders that the attacking troops would have "the full assistance of naval guns and high-explosive fire from the full strength of our howitzer and other guns." When once the main attack was completed, it should not be necessary for troops to expose themselves by passing over The Nek, since there had been already driven under No-Man's Land two shallow tunnels, which, as soon as the assault started, were to be converted into avenues of communication.

The two light horse regiments were in no way dismayed at their task. Had they possessed previous experience of pitched battle it is improbable that they would have faced so light-heartedly the prospect of attacking, along a high and exposed causeway, this hill, protected as it was by trenches eight deep and by well-posted flanking machine-guns. But the 3rd Light Horse Brigade had never yet seen any important offensive, and its troops accepted as almost certain the success of the big scheme, in which their attack was only a small part. They had so far experienced only the Anzac trench-warfare - eleven weeks of trench-digging and water-carrying; and when the orders for the attack arrived, all ranks became eager with the anticipation that within a few days they would have burst through the hitherto impassable trenches and would be moving through the green and open country. The prospect filled them with a longing akin to home-sickness. Four days before the attack, possibly in mistaken pursuance of an order which was cancelled in the case of other troops, their tunics were taken from them and they were left practically without clothes except their shirts, short pants, and puttees in which to fight. The order of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was:

Shirt sleeves, web equipment, helmets, 200 rounds, field dressing pinned right side inside shirt, gas helmet, full waterbottle, 6 biscuits, 2 sandbags (4 periscopes per each line and gas sprayers to be carried by fourth line), wire cutters, rifle (unloaded and uncharged), bayonet fixed.

Men and officers were ordered to stow what they could of their spare kit into their packs for storage. Most of the men crammed into some corner among their clothes certain specially-treasured mementoes - a fragment of Turkish shell, some coins bought of a prisoner, a home letter, a photograph or two. There was no chance of taking such treasures with them; they expected to bivouac on the open hills. The nights being cold, many obtained little sleep after their tunics had been taken away. But such was the excitement of anticipation that nothing could depress them. A number who were really too ill for fighting hid their sickness from the medical officer in order to avoid being sent away. Others-like Sergeant Gollan of the 10th Regiment - though too ill to escape observation, successfully begged the doctor to let them stay. Others again - like Captain Vernon Piesse of the 10th who had been sent away to the hospital ship on August 2nd contrived to get back from hospital on the eve of the fight. Piesse succeeded in rejoining during the night of August 6th. "I'd never have been able to stand up again if I hadn't,” he said.

In both light horse brigades, on the afternoon of August 6th, anticipation was raised to a high pitch by the sight of the 1st Infantry Brigade attacking at Lone Pine. For two hours the troops on Pope's and Russell's Top watched crowd after crowd of distant khaki-clothed figures running forward into the heart of the Pine and carrying onward that magnificent assault; and most of the onlookers had not the least doubt that at dawn next morning their own attack upon Baby 700 would be equally successful. Throughout the night wild bursts of rifle-fire were heard, first comparatively close at hand, then more distant, as the other assaulting columns worked into the hills. Lastly, a little before day-break, there came, far off and faint, a sound as of the bubbling of water in a cauldron. It was the rifle-fire at Suvla. About that time the attacking parties of the 8th Light Horse in the trenches on Russell's Top took up the positions from which they were to make the rush. Each squadron carried forty-eight bombs, and a reserve of 400 was to accompany each line. The first line had two scaling- ladders for crossing or clambering out of the deep Turkish trenches; and with each line were to go four small red and yellow flags, to be erected in captured trenches as a sign to the artillery and the staff. Behind the 8th the 10th, in similar kit, assembled in the rearward saps, ready to file into the front trenches as soon as the two lines of the 8th had gone forward. At 4 o'clock there commenced the “intensive" bombardment which was to precede the attack. All night long Phillips's, Caddy's, and Bessell-Browne's field-guns, the New Zealand howitzer battery on Anzac Beach, and "C" Battery of the 69th (British) Howitzer Brigade had each been firing single rounds at two-and-a-half minutes' intervals upon the enemy's trenches at The Nek and the Chessboard. The foremost trench at The Nek, and such trenches in rear of it as were on the seaward slope, could only be reached by the New Zealand howitzers. The shrapnel of the field-batteries was entirely harmless, but the howitzer shells inflicted serious loss. Occasionally one would explode actually inside some bay crowded with men of the 18th Turkish Regiment - the same which had made the desperate attempt of June 3oth, and which was still garrisoning The Nek. At frequent intervals throughout the night the Turkish infantry, crouching in their line, would find maimed and shattered comrades being bundled past them along the trenches. The garrison of The Nek was thus placed under a heavy nerve-strain. At 4 a.m. the artillery which had been engaged in this bombardment, with the addition of Trenchard's two mountain-guns, increased its rate of fire to four shells a minute. At the same time the guns of the supporting warships opened, concentrating upon Baby 700 and the trenches immediately below it at The Nek. At 4.27 (according to the watches of the artillery) for three minutes the batteries increased their fire to an "intensive” rate. Since the night of May 2nd no such bombardment had been seen at Anzac. The front Turkish trench, being very close to the Australian, largely escaped the shells, but the position behind it became an inferno, the dark-brown dust of the shell-bursts, dimly visible in the grey light, rolling in clouds across the face of the hill and shutting out all view from any distance. During this bombardment the two lines of the 8th Light Horse were waiting in their front trench. The trench being a deep one, pegs had been driven into the wall for the men to hold, and niches cut for their feet, so that when the signal came they would be able to spring out in a flash. Beside the first line on the fire-step stood the second, ready to give the men of the first a "leg-up." Three officers, with previously-checked watches, waited at intervals along the front, preparing to give the word for the charge. One of these was Lieutenant-Colonel A. H. White, the commander of the 8th, formerly a well-known Melbourne business man, who had insisted upon leading the first line of his regiment. The chance that such a leader would survive on such a day was obviously remote, and White, evidently realising this, had gone to the brigade office ten minutes before the start and held out his hand to the brigade-major, Antill. “Good-bye." he said simply. Two minutes later he was in position with his troops, with his eye on the second-hand of his timepiece. The men beside him showed no trace of excitement, hitching up their kit, and getting a firm foothold below the parapet.

For some reason, which will probably never be explained the bombardment which was then thundering upon the enemy ended-according to one account, "cut short as if by a knife" - seven minutes-before the watches on Russell's Top pointed to 4.30. The orders to the artillery were clear - that the guns were to continue until 4.30, when the land artillery would "stop" and the naval guns continue to fire upon targets farther back. There seems little question that there had been a mistake in the timing of the watches. Whatever the cause, the shelling of the enemy's forward lines ceased; the destroyers began to direct a less intense fire on to some of the more distant trenches. The rest of the artillery, according to order, became silent. On either flank of Russell's Top two Anzac machine-guns made ready to give covering fire to the attack. For three minutes hardly a shot was fired. But during that time the Turks, though severely tried by the night's experience, gradually raised their heads and, realising - that there was now no fire at all upon them, manned their trenches two-deep in anticipation of the assault which they knew must be imminent. One line seated on the parapet and the other standing behind it, they nestled their rifles to their shoulders, took aim, and waited. Their machine-guns here and there rattled off a dozen shots as they made ready for action. A spasmodic rifle-fire began, aimed at the Australian parapet, which was visible twenty to sixty yards away over the bullet-riddled stumps of dry bushes. Behind that parapet a few of the officers, looking at their watches, were perplexed at the sudden cessation of shell-fire. "What do you make of it? " asked Lieutenant Robinson of Major Redford. “There’s seven minutes to go." “They may give them a heavy burst to finish," was the reply. But none came. "Three minutes to go," said Colonel White. Then simply, “Go!"

In an instant the first line, all eagerness, leapt over the parapet. Facing them, not a stone's throw away, were hundreds of the enemy, lining two-deep their front trench and others behind it. The garrison had been reinforced the previous afternoon, when the Lone Pine bombardment started, the resting battalion of the 18th Regiment having been rushed from Mortar Ridge into the trenches. From that moment the crowded troops had waited for the attack. Consequently, the instant the light horse appeared, there burst upon them a fusillade that rose within a few seconds from a fierce crackle into a continuous roar, in which it was Impossible to distinguish the report of rifle or machine-gun. Watchers on Pope's Hill saw the Australian line start forward across the sky-line and then on a sudden grow limp and sink to the earth "as though," said one eye-witness,” the men's limbs had become string." As a matter of fact many had fallen back into the trench, wounded before clearing the parapet. Others, being hit when just beyond it, managed at once to crawl back and tumble over the parapet, thus avoiding trenches - the certainty of being hit a second and a third time and killed. Practically all the rest lay dead five or six yards from the parapet. Colonel White had gone ten paces, and the two scaling-ladders lay at about the same distance. Every officer was killed, but on the right, near the edge of the valley, Private McGarvie and two others survived between the bullets as if by a miracle, reached the enemy's parapet, and, since they could effect nothing single-handed against two or three tiers of crowded trench-lines, flung themselves down outside the Turkish parapet and waited, throwing bombs, of which they had a bag full, into the enemy's trench. They eventually crawled on to the slope of Monash Valley, where they were in partial shelter. On the other flank, near the seaward cliff, Lieutenant Wilson of the 8th also reached the enemy's trench and was seen sitting with his back to the parapet, beckoning to others to come on to him. Shortly afterwards he was killed by a bomb from the Turkish line. Here and there other individual soldiers had come near enough to the enemy's trench to throw a grenade, for the sound of the explosions could be distinguished for half-a-minute amid the uproar. But most of those who heard that fire realised that no attack could survive in it. The sound of bombing almost at once ceased. The first line, which had started so confidently, had been annihilated in half-a-minute; and the others having seen it mown down, realised fully that when they attempted to follow they would be instantly destroyed. Yet as soon as the first line had cleared the parapet, the second took its place, each man with his hand on the starting-peg and his foot on the step. The fire which roared undiminished overhead made it impossible to hear spoken orders. But exactly two minutes after the first had gone, the sight of leaders scrambling from the trench showed that the sign had been given for the further attack Without hesitation every man in the second line leapt forward into the tempest.

A few survivors of that line afterwards remembered passing most of the first, all apparently dead, lying six yards in front of its own parapet. The second got a little farther, since, after the fight, its dead lay a few yards beyond those of the first line. Captain Hore, who was leading on the right, where No-Man's Land was widest, by running as fast as he could reached a point fifteen yards from the Turkish trenches. There, glancing over his shoulder, he perceived that he was the only man moving across the bare surface, the rest appearing all to have been killed. He flung himself down at the point which he reached. None in that part of the line passed him.

Yet about this time observing officers stationed int eh trenches on Russell's Top undoubtedly saw, through the haze of dust raised trenches by machine-gun bullets, a small red and yellow flag put up in the enemy's front line. It was on the south-eastern corner of the trench. Who placed it there will never be known, but there were almost certainly a few men of the first line who had managed to get into the extreme right of the Turkish trench. For ten minutes the flag fluttered behind the parapet, and then some unseen agency tore it down. The fight in that corner was over; it could only have one ending. The Australian staff was subsequently told by a Turkish soldier, who had been in the front Turkish trench at the time and who was afterwards captured, that he knew nothing of any Australians having entered it alive. "They came on very well," he said, "and three men succeeded in reaching the Turkish trenches, falling dead over the parapet into the bottom of the trench."

These faint evidences are probably all that will ever be obtained concerning the incident. But its effects were important. After the second line had started, the men of the 10th Light Horse (Western Australia), forming the two lines which were next to attack, filed into the trenches which their predecessors had just left. In addition to the fire which had previously swept the parapet, two Turkish 75-mm. field-guns were now bursting their shrapnel low over No-Man's Land as fast as they could be loaded and fired. The saps were crowded with dead and wounded Victorians who had been shot back straight from the parapet and were being carried or helped to the rear. Among the Western Australians, who occasionally halted to let them pass, every man assumed that death was certain, and each in the secret places of his mind debated how he should go to it. Many seem to have silently determined that they would run forward as swiftly as possible, since that course was the simplest and most honourable besides offering a far-off chance that, if everyone did the same, some might at least reach and create some effect upon the enemy. Mate having said good-bye to mate, the third line took up its position on the fire-step.

The apparent uselessness of continuing the effort did not engender a second's hesitation in the light horsemen. They knew that their operation was a small part of the crucial struggle in the campaign, and, whatever their doubts, they could not feel sure that the whole structure of the plan might not depend upon their role in it. That they should falter, and "let down" their mates in the other columns at a critical moment, was unthinkable. Certain efforts, however, were made by the regimental leaders to discover whether the sacrifice was necessary. Major who commanded the third line, reported to the regimental commander, Colonel Brazier, that success would be impossible. Brazier, who during a slight relaxation in the Turkish fire had been able to raise a periscope, had himself seen the 8th Regiment lying prone in front of the trenches, either waiting for a lull in the fire or killed. About this time a staff officer from brigade headquarters came to him and asked why the third line had not gone forward. But Brazier, doubting whether the annihilation of additional troops could serve any interest except that of the enemy, determined to raise the question, as he had full right to do, before allowing that line to start. He accordingly at 4.40 went to brigade headquarters, which was slightly in rear, and finding there only the brigade-major, Colonel Antill, told him what he had seen, and informed him that, in view of the strength of the enemy's fire, the task laid upon his regiment was beyond achievement. But Antill, who was the main influence in the command of the brigade; had already received the news that one of the red and yellow flags had been seen in the enemy's trench. It seemed an urgent matter to support any troops who might have seized part of the Turkish line. He replied, therefore, that the 10th Regiment must push on at once.

It was then about 4.45. The roar of small-arms which had been called forth by the lines of the 8th had subsided to almost complete silence before the third line, formed by the 10th, went out. But as the men rose above the parapet it instantly swelled until its volume was tremendous. The 10th went forward to meet death instantly, as the 8th had done, the men running as swiftly and as straight as they could at the Turkish rifles. With that regiment went the flower of the youth of Western Australia, sons of the old pioneering families, youngsters - in some cases two and three from the same home - who had flocked to Perth at the outbreak of war with their own horses and saddlery in order to secure enlistment in a mounted regiment of the A.I.F. Men known and popular, the best loved leaders in sport and work in the West, then rushed straight to their death. Gresley Harpers and Wilfred, his younger brother, the latter of whom was last seen running forward like a schoolboy in a foot-race, with all the speed he could compass; the gallant Piesse, who had struggled ashore from the hospital ship; two others, who had just received their commissions, Roskams and Turnbull - the latter a Rhodes scholar. Sergeant Gollan, who had begged the doctor's leave to take part, was mortally wounded. Captain Hore of the 8th, still crouched far out on the summit, waiting to go on with any supporting line, did not realise that any such lines started. But as he lay he saw two brave men, first one and later another, run swiftly past him each quite alone, making straight for the Turkish rifles. Each, after continuing past him for a dozen yards, seemed to trip and fall headlong. They were undoubtedly the remnant of the two lines of the 10th Light Horse.

After the third line had gone, Colonel Brazier had again determined to prevent, if possible, further sacrifice of men. Major Scott, commanding the fourth line, had reported as Todd had done - that the task could not be achieved - and Brazier had therefore again referred to Colonel Antill, but was ordered to advance. "As the fire was murderous," wrote Brazier afterwards, "I again referred the matter personally to the brigadier (General Hughes), who said to get what men I could and go round by Bully Beef Sap and Monash Gully." While the question of stopping further charges over The Nek and attacking instead from a new direction was thus being debated, the fourth line had assembled on the fire-step The roar of musketry had again died down; but, as commands could not safely be given by word of mouth, the leaders had arranged that the sign to advance should be a wave of the hand. Major Scott was to give the signal to his troop leaders, and they would pass it to their subordinates. It was known to the troop leaders, but not to the men, that the stoppage of the assault was under discussion, when about 5.15 a.m. there appears to have come to the right of the line some officer who had possibly heard of the first decision of brigade head- quarters, and who asked the men why they had not gone forward. The incident is obscure, but the impression was somehow created that the charge had been ordered. The troops on the right at once leapt out. Instantly there burst forth the same tempest of machine-gun fire. As this uproar started, Major Scott, waiting near the centre, exclaimed: "By God, I believe the right has gone!" The nearest N.C.O's looked at Captain Rowan, their troop leader, who signed to them to go, at the same time rising himself and waving his hand, only to fall back dead from the parapet. His troop sergeant, Sanderson," repeated the signal, and the men in the centre sprang out. Sanderson's experience in this fourth rush has been recorded.

The rhododendron bushes had been cut off with machine-gun fire and were all spiky. The Turks were two-deep in the trench ahead. There was at least one machine-gun on the left and any number in the various trenches on the Chessboard. The men who were going out were absolutely certain that they were going to be killed, and they expected to be killed right away. The thing that struck a man most was if he wasn't knocked in the first three yards. Tpr. Weston, on Sanderson's right, fell beside him as they got out of the trench, knocked hack into the trench. Tpr. Biggs also fell next to him. Sanderson went all he could for the Turkish trench. Tpr. H. G. Hill, running beside him was shot through the stomach, spun round and fell. Sanderson saw the Turks (close) in front and looked over his shoulder. Four men were running about ten yards behind, and they all dropped at the same moment. He tripped over a rhododendron bush and fell over a dead Turk right on the Turkish parapet. The Turks were then throwing round cricket-ball bombs - you could see the brown arms coming up over the trenches. The bombs were going well over - only one blew back and hit him slightly in the leg. There were two dead men to the right towards the top of the hill, lying on the Turkish parapet - they looked like the Harper brothers. Sanderson knew how badly the show had gone. ... He managed to get his rifle beside him and clean it, and got the first cartridge from the full magazine into the barrel. He expected the Turks to counter-attack, and decided to get in a few shots if they did. After about half-an-hour, looking back, he saw Capt. Fry (of his regiment) kneeling up outside the " secret sap." Sanderson waved to him, and Fry saw him. ... The Turks were not up (i.e., lining their parapet) at this moment, because the navy had begun to bombard, and lyddite shells were whizzing low over the parapet and exploding on the back of the trench, so close that they seemed to lift Sanderson off the ground every time - he was sure the first short would finish him. Major Todd (who had survived from the third line) came along beside Fry and presently shouted something which seemed to be: "Retire the fourth line first." Sanderson looked round. There was none beside him except the dead. He crawled towards the secret sap ... about half-way there was an 8th L.H. man lying on his back, smoking. ... He said: “Have a cigarette; it's too _ hot.” Sanderson told him to get back and keep low, as machine-guns were firing from across the Chessboard and cutting the bushes pretty low. There was a lieutenant of the 8th L.H. there who had had some bombs in his haversack. These had been set off and the whole of his hip blown away. He was alive and they tried to take him in. He begged them to let him stay. I can't bloody well stand it," he said. They got him into the secret sap, and he died there as they got him in. In front of the secret sap were any number of the 8th L.H. The sap itself was full of dead. There were very few wounded - the ground in front of the trenches was simply covered. Sanderson went along the secret sap into the front line and there saw (dead) Cpt. Rowan, Weston, and another Hill and Lieut. Turnbull just dying then. ... About fifty yards of the line had not a man in it except the dead and wounded - no one was manning it.

It was at this stage that there were recovered a certain number of those who had gone out on the left and fallen wounded into ground which was partly sheltered. Lance-Corporal Hampshire, making five journeys, brought in Lieutenant Craig and others, the neighbouring Turks (according to one account) apparently refraining from firing at him. Most of the stricken, however, were on the exposed summit where no man could venture and live.

It appears that the left of the fourth line, although the brigadier's final decision did not reach it in time to prevent its movement, went forward more cautiously than the rest, the men keeping low and not running. They were partly in shelter, and, after advancing a short distance, flung themselves down among officers and men of other lines who were lying there. Among these was Major Todd, who, on discussing the position with other senior officers, decided, as has been related, to withdraw the survivors. Upon this being done, Todd received the brigadier's new order to proceed down Bully Beef Sap and Monash Valley, in order to support the detachment of British troops who were to assault from that direction. This step, however, was eventually abandoned, the impossibility of the plan being sufficiently demonstrated in the attempt made by the British to carry it out.

The plan of the attack had provided that, when once the enemy's trenches on the actual Nek had been captured by the first line of light horse, two companies of the Royal Welch Fusiliers should move up Monash Valley between Pope's and Russell's, and, when nearing its head, should climb the slope on the right and commence a flank assault upon the Chessboard, while a hundred yards farther east the 1st Light Horse from Pope's would also be frontally attacking. This assault would be impossible unless the trenches at The Nek were first taken, since their garrison would shoot into the back of the attacking British at seventy yards range. When, however, the red and yellow flag was sighted in the front trench on The Nek, the staff of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade considered the conditions sufficiently fulfilled to allow the British attack to proceed.

The two companies, together with some engineers of the New Army, had before dawn filed down Bully Beef Sap into the valley, up which they turned. Passing through the barbed-wire at the farthest Anzac post, they moved, one company up a steep washaway or indentation to the right, the other straight ahead along the main gully. At the limit of safety they waited for word of the capture of The Nek trenches. "At 5.10 a.m.," records their colonel, "a message was received that the Australian Light Horse were holding the 'A' line of trenches, and I was instructed to move forward at once."

In consequence of the dense undergrowth, Lieutenant- Colonel Hay had directed that the troops should be sent forward in parties of only ten at a time. Such a party accordingly began at once to climb the washaway; but no sooner had it moved than bombs were thrown at it from the enemy's trench, the parapet of which could be seen fringing the summit. The 1st Light Horse, watching from Pope's, observed the Turks running forward from their trench, rolling bombs down the cliff-face. The leading men of the Fusiliers were blown back and, in falling, swept away those on the uncertain foothold below. The enemy, who seemed inclined to follow, were instantly stopped by the light horse snipers, who quickly picked off a score of them. But the task of climbing the washaway seemed hopeless, especially as the muzzles of two machine-guns could be seen protruding over the parapet. Colonel Hay therefore decided to abandon the attempt. Meanwhile the other company had come, almost at its starting-point, into heavy machine-gun fire, its leader, Captain Walter Lloyd, had been killed, the subaltern next to him wounded, and every man in the first party hit. The company had thus been checked, and, as Colonel Hay found that the advance could only be made in single file and that any attempt to renew it was at once met by the fire of a machine-gun and by bomb-throwing, he reported to brigade headquarters that he was held up. The brigadier had diverted two companies of the Cheshire Regiment into Monash Valley, but, as the Fusiliers had failed, the attack there also was abandoned.

Thus by six o'clock the attack both on The Nek and by way of Monash Valley had been brought to a standstill. On' no other occasion during the war did Australians have to face fire approaching in volume that which concentrated on The Nek. From the whole face of Baby 700 and from secure positions far on both its flanks machine-guns swept that narrow space with a devastating cross-fire. In the 8th Light Horse half of those who started had been actually killed and nearly half the remainder wounded; that is to say, out of a total of 300, 12 officers and 142 men had been killed and 4 officers and 76 men wounded. The 10th Regiment had lost g officers and 129 men (of whom 7 officers and 73 men had been killed).

The Fusiliers had lost 4 officers and 61 men (1 officer and 15 men killed). The Turkish soldier before mentioned, who was in the enemy's trenches during this attack, stated that on The Nek during the actual assault the Turks suffered no loss." The 18th Regiment, which itself had been cut to pieces in endeavouring to cross the same narrow space on June 30th, felt that it had "got its own back." Complimentary orders were issued by the Turkish commanders contrasting that regiment with the 14th and others, which had lost their posts in the hills; some medals were granted and promotions were made for bravery.

Further Reading:

The Nek, Gallipoli, 7 August 1915

Roll of Honour, Australian, British and Turkish

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1919

Citation: The Nek, Gallipoli, 7 August 1915, Bean's Account