CHAPTER VIII

THE TURKISH EXPEDITION AGAINST EGYPT

ON a day in January, 1915, two horsemen rode down to the eastern edge of the Suez Canal. The few sentries or other troops who happened to be doing the work of the day on the western bank cast an idle glance at them. There was nothing unusual in a couple of officers riding along the high desert banks of the Canal. The horsemen presently turned away to the east. They were not British officers. They were reconnoitring for a Turkish army which was being launched across a hundred and seventy-four miles of desert against the Suez Canal.

Although the desert of Sinai, which stretches for 130 miles east of the Canal, was Egyptian territory, it was not occupied by the British, and very little news reached Egypt of any- thing that happened in it. But ever since the outbreak of war with Turkey it had been known that an expedition to Egypt was in preparation. The origins of this expedition went far back into the beginnings of that war.

While England and Turkey were still at peace a number of the forts of the Dardanelles, immediately ordered British troops at some of the wells. During those days the Turks, despite the secret treaty of August 2nd engineered by Enver Pasha, were divided in mind as to openly supporting Germany, and the Germans were striving to commit them. On September 26th the British fleet, always waiting for the Goeben and Breslau at the mouth of the Dardanelles, stopped a Turkish destroyer coming out of the straits. In retaliation Weber Pasha, the German officer then in charge of the forts of the Dardanelles, immediately ordered - apparently without the knowledge of the Turkish Government - the closing of the straits. Whether the Bedouin raid into Sinai was the result of German intrigue is not known. If so, it was not Germany’s last card; she held by then a trump ready to play when needed The battle-cruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau, which rushed into the shelter of the Dardanelles on August 11th after outwitting the British fleet in the Mediterranean, had been “sold” to Turkey in place of the two Turkish battleships which Great Britain had commandeered while they were building in England. Admiral Souchon and the German crews of the Goeben and Breslau remained in those “Turkish” ships, and through them Germany controlled the Turkish Navy. German officers were put into certain Turkish torpedo-boats, and on October zgth, while the Turkish Government still hesitated to enter the war, three of these boats raided the Russian harbour of Odessa before dawn, sank the Russian gunboat Donetz, damaged several Russian steamers and the French ship Portugal, and bombarded the town, while Admiral Souchon himself, with the Goebert and two destroyers, laid mines off Sevastopol. This purely German outrage committed Turkey to war. The allied ambassadors gave her the opportunity of avoiding that situation, the condition being that she should dismiss every German from her fleet. This the most powerful section of the Young Turk leaders, who constituted the Government, refused to do. In the meantime Russia declared war upon Turkey.

German diplomacy had completely won the Young Turks. As happens in many revolutions, the Young Turk leaders. who in 1908 had started at Salonica with the high ideal of regenerating Turkey into a civilised democratic nation, had found it necessary to employ methods of tyranny, and had long since begun to figure as ambitious and unscrupulous dictators. The three strongest men among them were Talaat Bey, Enver Pasha, and Djemal Pasha. Talaat Bey, a Mohammedan probably of Bulgarian descent, was a man of crude powerful character who had started life as a telegraph operator and was now Minister for the Interior; Enver Pasha, Minister of War, was riot yet forty, handsome, brave, able, quick in decision, intensely vain, an ardent advocate of “Turkey for the Turks,” but an imitator of Western manners and a passionate admirer of all things German; Djemal Pasha, formerly a major on the Turkish staff, was an able, ruthless, vain, and ambitious man, also devoted to the idea of “Turkey for the Turks,” but far less under German influence than his two colleagues. He had been Military Governor of Constantinople at the time when Enver and Talaat were getting rid of all their opponents in the capital and in the army. He was now Minister of Marine.

On October 31st Turkey entered the war.

To strike a blow against Britain in Egypt, where her rule was believed to be insecure and where her line of communications with India and Australia was exposed, was one of the first objectives of both Germans and Turks. Early in November, Djemal Pasha started from Haidar Pasha railway station, opposite Constantinople, to take command of the 4th Turkish Army in Syria, which was to invade Egypt.

The news which reached Egypt of this army was very indefinite. The Turkish Army had been reorganised since the Balkan War. In 1913 Enver and Talaat had arranged with Baron von Wangenheim, the German Ambassador at Constantinople, for a German Mission to carry out this work. There had been foreign missions to reorganise the Turkish forces before this the mission of von der Goltz Pasha to instruct the army, and that of Admiral Limpus, from England, to train the navy. But General Liman von Sanders, who was sent in 1913, came as the personal representative of the Kaiser. He was made Inspector-General of the Turkish Army, while General Broussart von Schnellendorf became Chief of the General Staff. German officers, scattered through the army in important commands, worked with immense vigour.

“In six months,” says the United States Ambassador of that period, “the Turkish Army had been completely Prussianised. What in January had been an undisciplined ragged rabble, was now parading with the goose-step; the men were clad in German field-grey, and they even wore a casque-shaped head- covering which slightly suggested the German pickelhaube.”

The 4th or Syrian Army had been organised to consist, as did the army in each main area of the Turkish Empire, of the divisions raised in that area. But the Turks had no trust in the Syrians and Arabs composing it. The Syrian standard of education is high, and many Syrians had more sympathy with the French and British than with the Turks. The Arab, who is a light-hearted southerner, a fickle larrikin compared with the slow, stolid, dependable Turk, was not greatly valued by the Turks as a soldier. Information came through to Egypt early in the war that the Turks were moving troops from their great agricultural and pastoral province of Anatolia down into Syria, and were transferring Syrian officers and men to other parts of the Turkish Empire.

The crossing of the Sinai desert is a vast undertaking. Many Englishmen in Egypt would not believe that the Turks seriously intended to attempt it, but were convinced that the threat was made in order to detain British troops in Egypt. There was no continuous railway connection between Turkey and Palestine; German and Swiss constructing companies were still working on the tremendous difficulties of the tunnels through the Taurus and Amanus mountains. From the south- eastern end of these mountains a continuous railway led through Palestine, but it ended short of Nablus, north of Jerusalem. The famous “pilgrims’ railway,” which ran through the desert on the far side of the Dead Sea and of the Sinai desert to Medina, could not safely be made the sole line of communications of an army. It is true that the Egyptian pilgrims regularly passed by a desert road 170 miles in length across the south of Sinai to join this railway at Ma’an near the head of the Gulf of Akaba, and the Turks at an early stage of the war thought of pushing a railway towards Egypt by this route. But the steepness of the desert gorges, and the fact that the British cruiser Minerva was daily visiting the head of the Gulf of Akaba, made the route unsuitable for a large force.

About Christmas rumour after rumour arrived in Egypt of vast preparations in progress on the other side of the Sinai desert. The staff of the 4th Turkish Army was requisitioning camels, fodder, and utensils of every sort. At least 80,000 troops were in Palestine, and a large proportion of them was gradually being concentrated in the south, not close to the sea where they would be within range of French hydroplanes or British naval raids, but thirty miles inland at Hebron and further south at Beersheba, forty miles by road from the Egyptian frontier. The railway towards Nablus and Jerusalem was being hurriedly built with rails pulled up from other lines. Early in January advanced parties from the troops at Beersheba were heard of at El Auja, a police post on the Turkish side of the Egyptian border, and at Kossaima, a few miles on the Egyptian side. Others had appeared on the coast of the Mediterranean at El Arish, the main town on the coast road, thirty miles within the Egyptian border.

Even at this date there was much doubt in Egypt as to whether the expedition was seriously meant. The Turks could not hope for much success without heavy guns. They were known to have sent some of these guns to the south of Palestine, but most British officers, from General Maxwell down, doubted whether the Turks could possibly bring them across the desert. The rainy season, during which any expedition would have to be made, would end within two months. The only practicable road, as the southern route by Akaba had not been adopted, would presumably be the caravan route near the Mediterranean, where the wells were plentiful, But where the Turks would be easily observed. It was a gigantic undertaking, and many held that it was far too difficult for a Turkish staff to attempt.

The troops defending Egypt were entirely new arrivals, who had taken the place of the British garrison. One of the first steps adopted by the British was to establish a series of posts along the Suez Canal. The Canal, which runs 99 miles from Suez at the head of the Red Sea to Port Said on the Mediterranean, was nowhere less than seventy yards in width. At the northern end, where the desert had been intentionally flooded, it was unapproachable, and the same was the case where it ran through the Bitter Lakes. The posts, consisting of Indian troops, had been placed along the rest of the Canal. and these remained as the system of defence. The desert of Sinai had been entirely given up, the Egyptian border becoming, in actual fact, the water of the Canal itself.

Indeed, only at a few points were troops maintained on the eastern bank of the Canal. The theory was to make the water of the Canal the main obstacle, and to hold the eastern bank only at a few ferry-heads, so that troops could be thrown across, if necessary, during battle. The most important of these were at Kantara in the northern sector, where the caravan route to Palestine crosses the Canal; at El Ferdan and Ismailia, about half-way down the Canal, where it enters Lake Tinisah; at Tussum and Serapeum, two stations of the Suez Canal Company on the eight miles reach between Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lakes; and at Shallufa, Kubri, and Shatt (where the road from Ma'an comes in) between the Bitter Lakes and Suez. Small entrenched posts were dug on the eastern bank at these places. The bulk of the garrison of the Canal was kept in scattered posts on the western bank. The trenches of the posts were on the top of the Canal bank, which was often fairly high by reason of the embankment thrown up in digging the channel. In front, like a moat, ran the Canal, and up and down it moved the world’s traffic. Often the garrisons of the posts were camped behind the slope of this bank, their tents being hidden from the desert of Sinai and sometimes from the ships.

The Indian infantry on the Canal consisted of the 10th and 11th Divisions of the Indian Army. They were organised less in divisions than in three sections to defend the three main land reaches through which the Canal ran Suez, Ismailia, and Rantara. There were strong posts about every five miles on the eastern side and small posts every half-mile on the western side. A brigade was in reserve at Suez, another at Kantara, and two at Ismailia. Major-General Alex. Wilson, who from being the senior brigadier among the troops from India had become the Officer Commanding the Canal Defences, had his headquarters at Ismailia. They had no artillery except a few small Egyptian guns, but, as a great reserve behind them, in Cairo were the Lancashire Division (42nd), the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, and the British Yeomanry, all of which possessed artillery. Positions had been prepared for field guns, in case they had to be brought to the Canal For heavy artillery certain warships were stationed at either end of the Canal, ready to be moved where required. They had ranges marked in the desert, but along certain reaches, where the Canal ran through a cutting in the sand like that of a railway, their guns could not fire over the banks. A number of tugs had been armed with small guns. Searchlights were mounted on lighters or on the banks.

Early in January the 3rd Field Company of Australian Engineers, under Major Clogstoun, had been sent down to construct trenches and floating bridges on the Canals The British authorities at once began to discover in this company men experienced in almost any work which was needed. Within a week some were detached to manipulate searchlights, others had taken over the power-house at Ismailia, others were surveying for artillery ranges or for maps, while the main body was making bridgeheads at Serapeum, Ismailia, and Kantara, and also a floating bridge for Ismailia ferry-post.

Although very little was seen or heard of the Turks, they undoubtedly visited the Canal during this period. Small patrols of the Indian infantry, four or five men and a non-commissioned officer, used to move along the eastern bank daily between the “bridgehead” posts on that side of the Canal. Larger patrols of the Bikaner Camel Corps or of the Imperial Service Cavalry (from the native States of India) rode daily some miles out through the desert. The seaplanes at Port Said and Suez were heavy, and found it difficult to go far inland. Even some of the aeroplanes at that period could not make enough height to fly over the plateau in southern Sinai. It was only at the beginning of 1915 that an aerodrome was constructed at Ismailia, and the aeroplanes were machines of old pattern. The men who flew them realised that aeroplanes were seriously needed on the Western front, and that the Suez Canal Defences would have to make the best of such old material as could be spared. For this reason the range of air reconnaissances into the Sinai peninsula was at most sixty miles. On one occasion the cavalry went out and deposited a store of petrol in the desert, and by this means a prolonged flight was made in two stages to the desert village of Nekhl, eighty miles out in the centre of Sinai on the road to Ma’an. Three hundred troops with horses were observed at that place. Ordinarily, however, the reconnaissance went no more than forty miles over a desert which showed not the least sign of life. On rare occasions a Bedouin patrol was sighted.

But on January 15th came news that Turkish troops had entered Sinai in considerable numbers. On January 18th a French seaplane flew from the sea to Beersheba, where it found a force of 8,000 to 10,000 troops. As a matter of fact the main part of Djemal Pasha’s army was already far within Egyptian territory, hurrying by long night-marches to the Canal. The 73rd Turkish Regiment, for example, had left Jerusalem as long ago as January gth, and Beersheba on January 12th; by January 17th it was crossing the upper reaches of the Wadi el Arish, twenty miles inside the Egyptian border.

Djemal Pasha or his staff had made a move which was completely unexpected. Instead of marching along the route constantly used by the generals of history from the times of the Pharaohs to Napoleon, namely, the caravan road near the sea, where an army would have been observed by seaplanes and possibly shelled by cruisers, the Turks followed a line through the centre of the Sinai Desert which had never been attempted by any army before.

The main strength of Djemal’s army of invasion was the VIII Turkish Army Corps-the Damascus corps of the Syrian army. The Turks had pledged themselves to the Arabs in 1914 that it should be recruited locally. Whey war broke out, however, the Turks, not trusting the Arabs and Syrians, sent many of them to other armies, and in exchange brought many Kurds and Turks into the VIII Corps. Djemal took for the “Army of Egypt” the following units, composing nearly the whole of this corps:

VIII TURKISHARMYCORPS:

Mounted troops:

29th Cavalry Regiment and a Camel Squadron.

Engineers:

4th and 8th Engineer Battalions.

Infantry:

23rd Division (Homs)-

68th Regiment.

69th Regiment.

25th Division (Damascus), with part of 25th

Artillery Regiment-

73rd Regiment.

74th Regiment.

75th Regiment.

27th Division (Haifa), with part of 27th Artillery Regiment-

80th Regiment.

81st Regiment.

The Syrian army was reinforced, after the outbreak of war by some divisions of purely Turkish troops from Anatolia. The railway tunnels through the wild steeps of the Taurus and Amanus mountains were not yet finished. The Taurus gap was easily crossed by road, but the Amanus gap was much more difficult. The troops were sent by rail to Alexandretta, the Turkish port in the angle of the Mediterranean between Asia Minor and Syria; from Alexandretta they marched straight over the Amanus mountains to rejoin the railway beyond the break. The railway to Alexandretta and the road up the mountains were completely open to the guns of any warship, and on December 17th and 18th the British cruiser Doris shelled this stretch of railway and destroyed certain bridges and a train loaded with camels. On December 21st she forced the Turks at Alexandretta to blow up two of their own railway engines. But the 10th Turkish Division, complete with its guns and pontoons under the German Colonel von Trommer, had disappeared over the Amanus road a week before. Two other Turkish regular divisions, the 8th and 9th, had also passed into Syria, but did not move down to Palestine for Djemal’s expedition. The troops with the 10th Division seem to have included the following :

4th Battalion of Engineers (from IV Army Corps to which the 10th Division belonged).

10th Division, with part of 10th Regiment of Artillery-

28th Regiment.

29th Regiment.

30th Regiment.

A battery of heavy guns (5.9-in. howitzers).

Besides these troops Djemal had the assistance of part of the independent division which the Turks maintained in Arabia :

22nd (Hedjaz Independent) Division

Part of 128th Regiment.

Part of 129th Regiment.

A few attached troops, including some irregular cavalry, completed the Army of Invasion. Its total strength was about 25,000.

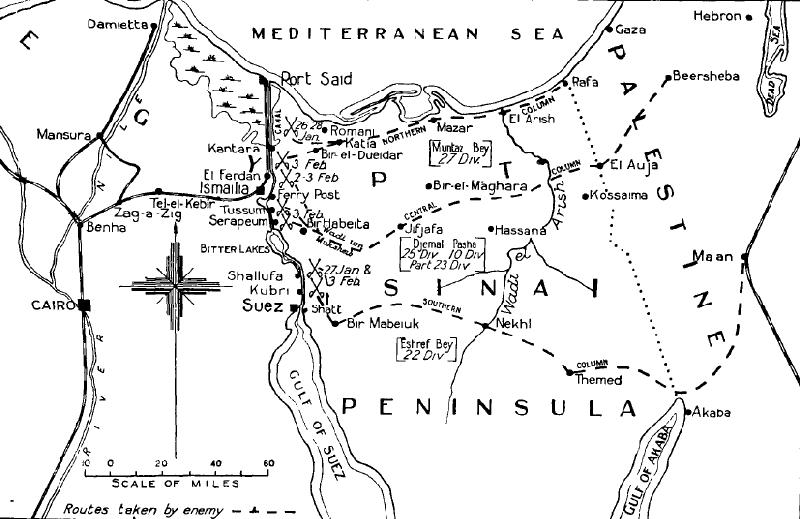

This force marched along three routes towards the Suez Canal. The 27th Division coming from Haifa, on the coast of Palestine, was sent under Muntaz Bey, with part of its artillery, along the northern coastal route through El Arish. By January 26th this force was at the wells of El Dueidar. close to the Indian outposts at Kantara, who could see the heads of the Turkish soldiers as the latter entrenched them- selves behind the distant sandhills. A few shells came singing over from the Turkish guns, but after a small reconnaissance the enemy appeared content to dig himself in on the horizon. Some troops of the Hedjaz Independent Division, with the 69th Regiment (23 Div.) and African Irregulars, marched, under Eshref Bey, from Ma’an past the head of the Gulf of Akaba and by the southern route across the Sinai Peninsula. The British cruiser Minerva and two destroyers had been constantly watching the head of the gulf. But the weakness of warships in attacking land defences was again impressed on every sailor in those waters by the fact that two small Turkish 12-pounder field guns, hidden somewhere in the hills, made it necessary for the Minerva to shift her position. Eventually she used to visit the place by night and employ her searchlights. About 3,000 troops, Turks and wild irregulars, traversed the southern route. They were found, on January 22nd, about thirty miles from Suez.

The main body marched with Djemal by the central route. It consisted of the VIII Corps, but with the 10th Division included instead of the 27th, which had moved by the coast. The 25th Division was leading, with part of the 23rd, the guns, and the pontoons. The 10th Division for some reason was several days in rear. The march of this central Turkish column of at least two divisions with their guns and pontoons across the centre of Sinai, by a route which the British authorities till then believed impossible for large bodies of men - without a railway or even a pipeline for water - was, according to Djemal Pasha, accomplished without any loss at all. On January 22nd, when the 73rd Regiment of the 25th Division, after helping to pull the guns through the desert, was thoroughly exhausted and was allowed a day of rest, Djemal visited them at their desert halt and addressed them. He told them that the route of their march had never been used by an army before. Sultan Selim and the great Egyptian general Ibrahim, when they crossed Sinai, had taken their troops by the coastal route through El Arish and lost half of them.

“But we have lost not a single animal,” he said. He asked the infantry to help the artillery drag the guns, since these were most important for the crossing of the Canal.

The organisation for this expedition must have been something entirely new to the Turkish Army. But it was not altogether the work of Germans. The Chief of Staff was a Bavarian colonel, Kress von Kressenstein, and many German officers accompanied the expedition. The transport was in charge of Roshan Bey, an Albanian. But without a fine spirit in the Turkish regular troops, under their own officers, such an achievement as this march would have been impossible. The diary left by an Egyptian boy, who had enlisted from a military school in Constantinople and marched with the 73rd Turkish Regiment, and who was afterwards killed on the Canal, tells of this journey from day to day. He had joined with an enthusiastic desire to relieve his country from the domination of the British, and he left a letter to his parents saying that he knew he was going to die. The trials began on the first day out of Jerusalem, when, after passing Bethlehem, they had to sleep in mud and water in “hardship (he wrote) undreamt of by the most miserable of men” Even before Beersheba they met with heavy going over stones, and the youngster had to remain behind with swollen feet. On January 18th, the day after crossing the Wadi el Arish at a point thirty miles inland, the 73rd Regiment was so worn that, when the march stopped, the watering-place which it was intended to reach was still four hours away. The troops were suffering from thirst. They reached water on the morning of the 18th, having during that stage helped to drag the guns. The water on this march, being pumped from desert pools or wells, was always brackish.

The diary says that on their next stage the troops were almost fainting from thirst, until at noon, after a march which began at midnight, they reached purer water than they had vet tasted. It had been pumped for them from a well or pool into the pontoons of their engineers. The next day the guns had to be dragged through the desert. On January 20th some of the troops enjoyed a day’s rest. On the night of the 23rd the head of the column started shortly after sunset, and marched through the night and until noon next day. The following night, almost immediately after the start, it entered a difficult gorge leading down from the highlands of Sinai, and after sunrise the troops camped at a waterhole at the bottom. The column had worked down the gorge of the Wadi um Muksheib from the plateau to the plain. Thirty miles across the sandhills lay the Suez Canal. The troops were within range of the Ismailia aeroplanes, and they were ordered to cut the desert scrub and make shelters, under which they could sleep without being observed. Two days later, on January 26th, a British aero- plane found them there.

The trained Turkish soldiers, although they were slow of thought and movement and generally very ignorant, were by no means the dumb driven cattle which the public was led by the optimism of official reports to picture. The Sultan had declared what amounted to a Holy War against the Allies. The sacred standard had been brought from Medina and shown to the troops at Jerusalem. The Young Turk doctrine of “Turkey for the Turks” had probably aroused some response even in the most ignorant. Those officers and men who had received any education bitterly resented the way in which Turkey had been shorn of some of her islands by the Greeks, and of others by the Italians. Although the Treaty of London allotted some of the Turkish islands to Greece, the Young Turks refused to recognise the arrangement. They had raised by public subscription the funds for building two super- Dreadnought battleships in Great Britain. with the openly avowed intention of taking back their islands from the Greeks. The Greeks had hurriedly bought two cruisers from the American Navy. And now, when the Turkish battleships - which had been built at the cost of such sacrifices and upon which so much depended - were ready for their trials, the British Government had exercised its right of pre-emption and bought them. Unquestionably Britain was justified; she could not hand the battleships to a probable enemy to be used against herself. The only other course open would have been to send them to Turkey with British crews.

But the bitterness among the Young Turks at the taking over of these ships was intense. Captured Turkish officers almost always referred to it. The idea of ridding Egypt of British rule was also a popular one with the Turks. They had never been reconciled to the loss of their old province, and Djemal in particular was bitterly resentful. On account of the intrigues of the Khedive, Abbas Hilmi, in Constantinople and Switzerland, the British, on December 18th, had deposed him and proclaimed his uncle, Hussein Kamil, as Sultan of Egypt, independent of the Turks, under British protection.

Britain had thus officially annexed what in reality she already held. Djemal and his army looked upon themselves as the “liberators of Egypt.” They expected that, the moment news arrived in Egypt that a Turkish Army had crossed the Canal, The Egyptians would rise against the British and welcome the Turks.

Nor is there any doubt that, although Egypt under British rule was as prosperous as she had been miserable under Turkey, the feeling in Egypt-among those classes in which any feeling existed - was entirely for the Turks. Britain could not trust the Egyptian Army, though a few units were still employed and kept their arms. The effect of the Turkish approach to the Canal and, later, of any supposed Turkish victory during the Gallipoli campaign, was always immediately noticeable in the demeanour of the Egyptians. In January, 1915, an educated Syrian was urging upon an Egyptian the benefits of British rule after the oppression by the Turk: at that moment the Turks were preparing for war by robbing Palestine, and the British were preparing for war by flooding Egypt with the money of their purchases. The Egyptian admitted everything, and at the end - “I would rather live in a Turkish hell than in an English paradise,” he said. The Turkish troops therefore came to the Canal with a certain enthusiasm. Their officers knew why they were fighting; it had been preached to the men; and though they were dull and stupid, they were convinced. Unlike the changeable Arab, the Turk, when convinced, clings stubbornly to his conviction.

When the head of the Turkish column began to appear, most unexpectedly, opposite a point half-way down the Canal, it was at first thought that this was probably a small force diverted from the northern road by which the army was expected. Only two comparatively small bodies of 2,000 or 3,000 men each were sighted opposite Ismailia. The authorities in Egypt were expecting a force of at least 30,000 men. and possibly an army far more numerous. The force which now began to appear at the mouth of the Wadi uni Muksheib was therefore judged to be either the advance guard of a much greater army or else a smaller force intended for a demonstration. In any case the time had clearly arrived to man the Canal defences. Most of the field artillery of the East Lancashire (Territorial) Division had already been brought up and distributed behind the western bank of the Canal, and the trenches along that side, which had not before been manned, were now lightly garrisoned by detachments of Indians from the reserve brigades.

On the 26th the warships were moved to their stations in the Canal. Further Indian troops were placed upon the western bank, and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade arrived from Cairo. The Wellington and Otago Battalions were sent to Kubri, above Suez; the rest remained in reserve at Ismailia. A few New Zealanders were posted in the trenches at El Ferdan and Ismailia Ferry. Two platoons (a hundred men) of the Nelson Company, Canterbury Battalion, were detached to reinforce the garrison of Serapeum, on the reach between Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lake. These eventually formed two small posts on the western bank. About a mile south of them was the Serapeum ferry ; about two miles north was the Tussum ferry. At each of these there was an Indian post on the Turkish side of the Canal. Between Tussurn Post and Serapeum Post the high sandy eastern bank was empty. The small posts of New Zealanders, like the 62nd Punjabis and other Indian troops garrisoning the western bank, looked down over the water of the Canal at the bare bank opposite and the small wave-like tussocks and hillocks surrounding it. Here and there, where the bank was low, they could see past some dip in the desert to the high sandhills five or ten miles away on the horizon.

It was clear that the advanced parties of Turks appearing at Kantara and Kubri and in the foothills opposite Ismailia covered the approach of a Turkish army. The general opinion was that they were an advance guard reconnoitring the British positions and making preparations on the ground for the reception of a great army which was to follow them. Life went on as usual in the camps behind the Canal. The transports of the second Australian and New Zealand contingents passed up the waterway amid the usual cheers, which were especially loud when the troops on the banks recognised the Australian submarine AE 2 moving awash up the Canal. On February 1st the Indian outposts at the ferry-post beyond the Canal at Ismailia noticed troops moving among the distant sandhills, and the next day a desultory action was begun between these and a body of Indian troops which advanced into the hummocks opposite Serapeum and Tussum. An one of the fierce parching winds known as the “khamsin,” bringing a mist of dust, in which the fighting was broken off. That night, which should have been bright with a big moon, was densely dark. Clouds, intensified by the flying sand, shut out the sky. Within the last few days an odd sniper or two from the enemy’s camps in the desert had pushed forward into the hummocks opposite Serapeum and Tussum. An occasional shot had been fired at ships moving through the Canal.

But this night was perfectly quiet.

About 3.20 a.m. an Indian sentry on the western bank of the Canal some half a mile south of Tussum, looking out towards the dark empty bank opposite, heard an order given in a gruff voice on the other side of the water. Peering in the direction of the sound, he made out dark figures busily engaged upon some work - probably digging - on the near side of the opposite bank. He fired. A short splutter of rifle shots broke the silence of the night. Then there was peace for ten minutes. “Firing at nothing, I suppose, as usual,” said a staff officer, hurrying towards the sound.

Possibly ten minutes later another sentry, half a mile further north, noticed movements at the foot of the Canal bank opposite him. Men were launching a boat. The sentry fired, and a vigorous fusillade followed. The western bank at this point was held by half a company of the 62nd Punjabis. The officer commanding the post, Captain M. H. L. Morgan, was sleeping in his tent close behind the embankment. A roar of rifle fire awoke him, and he ran to the top of the bank. Below, on the water of the Canal, a boat with a number of dark figures was just arriving at the bank on which he stood. Morgan charged with his half company down the slope and met the Turks as they were in the act of landing. Morgan was hit through the shoulder, but the twenty-five Turks in that boat were shot down. One other boat struggled across at this point under a terrible fire. It reached the Egyptian bank; the survivors were seen to scramble ashore; they began to scrape the hard sand with their fingers in an effort to get cover. Six were killed, four captured on the spot. Lying close under the bank, the remainder were difficult to see, but they surrendered in the morning to a party of Indians from further south.

Three-quarters of a mile southward another boat reached the British bank, but a British officer and a party of the 62nd Punjabis charged this also and killed or wounded all its occupants. A native Egyptian battery, firing shrapnel with zero fuse from the top of the bank, was said to have sunk another.

The two platoons of New Zealanders were further south again, in two posts rather nearer to Serapeum than to Tussum, with some distance between them. Behind them, along the whole length of this portion of the Canal, was a narrow plantation of pine trees, and in the rear of this was the 19th Battery of Lancashire Field Artillery. At 3.20 the New Zealand sentries had heard a sound like the rumble of waggons in the desert beyond the Canal. They knew it must come from the enemy, and imagined that he was moving his artillery. A messenger was on his way up the bank to report it to Major C. B. Brereton, who commanded the New Zealand posts, when heavy rifle fire broke the silence. It was to the north of them. Presently above the rifle shots the bark of three Turkish machine-guns could be distinguished. Major Brereton rail to his northern post, in which there were about thirty men. From there could be seen the stab of flame from a machine-gun on the far side of the Canal, about 300 yards further north. As no certain enemy was visible, Brereton ordered the officer in charge to hold his fire, and returned to his southern post.

Shortly afterwards a message came from the left asking the northern post to move up thither. The New Zealanders hurried towards the flashes Presently they made out in the water ahead of them several boats. Men could be seen trying to get them under way. The water's edge here spread out into a narrow beach, along which were some thirty or forty large tree-stumps, which seemed to have been pulled from the Canal during its construction and left there. The New Zealanders ran to these stumps and opened a heavy fire upon the boats. The crews appeared to be staggered by it. and the boats, after muddling or drifting with the slow current for about fifty yards northwards, put back to the eastern shore Until daylight there were forms round them busy upon some work or another.

Meanwhile other Turks were moving among the tussocks above the opposite bank. A line of them stood against the skyline digging, and this line was always extending south- wards, until it reached a point opposite the southern post of the New Zealanders. The northern post could see at 150 yards the digging Turks with their backs bent and their spades shovelling, and. although the New Zealanders fired at them continuously, the figures worked on until daylight. There came no sound except the fire of the rifles. Only once in the night the New Zealanders heard a human cry.

With daylight Brereton, now with the northern party, withdrew his men to the top of the bank in order not to have them overlooked. The Turkish rifle-pits crowning the opposite slope were completed, and the only sign of the Turks was a row of Turkish rifles stuck up against the sky like the hairs of an eye- lash. The New Zealanders had the trees behind them whereas the Turks were on the sky-line. This, and the spirit of the men, gave them a complete mastery of fire over the enemy. They were able to keep their heads up, literally enjoying the game, while the Turk kept his down. The Turkish method of firing was pathetically simple. A rifle in the line opposite would be slowly lowered until it pointed at the British bank. Every Indian or New Zealand rifle in sight would instantly be aimed at it. A Turkish skullcap would cautiously appear behind the lowered rifle and a Turk would attempt a hurried shot. At once a score of New Zealanders or Indians would let fly at him. Below, by the Canal's edge, the boats floated idly with a cargo of dead and dying. The Turks had mostly retired up the bank before daylight. But a few remained, trying to hide behind their boats. During the day, as these bolted up the bank, they were riddled with bullets. Nevertheless four Turks, who had dug themselves into four small rifle-pits at the water's edge, kept up all day an annoying fire.

Dawn found a fairly strong force of the enemy lining the eastern summit of the Canal bank, but pinned down by heavy rifle fire. On the Canal floated ten or eleven of their iron pontoons, the dead still in and about them. The Turks had planned to bring their boats through certain openings in the bank which afforded a gentle path to the water's edge. One of these was seventy yards from the sentries in Tussum post. The Turks for their part did not know of this post, and a detachment of them actually carried a pontoon down this channel without being seen or heard. When met by fire from the far bank, they retired into the gutter and thence into one of the outer trenches of the post only occupied by day. From that position they kept up a rifle fire during the night. In the morning they found themselves iii a trap, Indian machine-guns, under Captain W H Hastings of the 92nd Punjabis, looking into them from both sides. Of some 200 Turks here huddled together 10 were killed and 60 wounded. Two small parties of Indians were sent out during the day. and the survivors surrendered to them.

For two miles south of this point, however, the Turks were holding a position along the bank from which no British force could drive them except by crossing the Canal. The enemy had lost very heavily, the Indians and British scarcely at all. But there were certainly other Turks in the desert behind, and eleven Turkish pontoons lay along the water's edge. Accordingly Brigadier-General S. Geoghegan, commanding the 22nd Indian Infantry Brigade, and senior officer in this part of the line, decided to fling what troops he could spare across to the Turkish side at Serapeum ferry, cut off the Turks lining the bank to the north of the post, and clear at least the Suez Canal bank of them. At the same time he asked Lieutenant- Commander Palmes, who commanded torpedo-boat No. 043, to blow up those pontoons which were still undestroyed.

It is probable that at this time the Turkish commander him- self knew very little of what had happened. His troops had gone forward. delayed, it is true, by the sand-storm, but other- wise without a hitch. It was the 25th Turkish Division which attacked. Its three regiments, the 73rd, 74th, and 75th, were to be formed up for the start at 6 o’clock the night before, and were to move to a rendezvous 5,000 yards from the Canal. Here the waggons were to be left behind and the pontoons carried by squads of eighteen men, with engineers attached, straight to the Canal. Half the companies were to advance with the pontoons and attack; the other half were to follow some distance in rear to act as supports.

The enemy had not expected to find any posts on the eastern side of the Canal, their patrols having visited its bank without noticing anyone except perhaps a sentry. On approaching the Canal the advancing troops took off their boots and threw away pannikins or anything likely to clatter. There were to be no cigarettes and no talking. Officers were personally to see that no rifle was loaded. Entrenching tools were tied so as not to flap. The Turkish machine-guns took positions on the eastern bank in order to open-as they did- the moment the crossing was opposed. The supports came up closely and lay hidden behind the eastern bank. The plan was that, when the foremost troops had crossed and seized the Egyptian bank, the rest of the 75th Regiment on the right was to turn northward and take Tussum. The 74th was to advance towards Lake Timsah and seize the railway; the 73rd was that, when the foremost troops had crossed and seized same time, and just north of the main attack, one regiment of the 23rd Turkish Division-the 68th-was to assault Ismailia and El Ferdan; and, in rear, the greater part of the 10th Division was to move up as reserve. The heavy battery, escorted by one battalion of the 10th Division, was to take position during the night at Bir el Murra, opposite the southern end of Lake Timsah, and, if possible, to sink one of the war- ships where the Canal enters the lake. Subsidiary attacks were to be made at Kantara, Suez, and other points.

Apparently twenty-four pontoons were to be carried, besides a number of rafts made from kerosene tins. Of the pontoons, at least sixteen reached the water’s edge; one remained with its nose visible on top of the bank; another was a little further back. Palmes in his torpedo-boat moved up the Canal under the eyes of the Turks, but they could not raise themselves to fire at him. He blew up with gun-cotton or with his small bow-gun the boats on the water’s edge. Seeing the bows of a pontoon on top of the eastern bank, he landed in a dinghy with two or three seamen. On reaching the summit of the bank he found himself almost stepping upon five Turks lying in rifle-pits. He raised his rifle, when, under his elbow, he saw another prostrate Turk with fifty or more behind him. The nearest men were looking up at him in surprise and clumsily shifting their rifles. With a whoop, amid the laughter of the New Zealanders, he dashed back down the bank and reached his boat.

Meanwhile about 500 Indian troops had been sent out from Serapeum. They worked forward a short distance, some going through the sand hummocks and others under shelter of the Canal bank, the latter receiving some fire from their rear, apparently from the few Turks who had crossed the Canal and were still under the British bank. Their advance was presently held up by the enemy in the hummocks. The Indians and the Turkish supports lay facing one another firing.

With daybreak the Territorial battery from behind the New Zealanders had opened upon the Turkish supports in the hummocks, and. later, upon bodies of Turks whom their observers could see in the desert behind. Considerable numbers were moving into the hollow some miles east of the Canal. The Turkish commander, not having news from his front line nor being able to obtain any, except that a few boats had crossed, was pushing up part of the 10th Division, which was his reserve. Part of the 28th Regiment was apparently put in. But the Territorial artillery quickly found the range. Many New Zealanders stood up cheering at the shots, until the enemy's field artillery opened upon the plantation where they stood. The Turkish column flinched under the fire of the Lancashire battery. A large shell from the old French battle-ship Requin, moored in Lake Timsah, fell into the mass of men. The reserves drew off. The attack of the 68th Regiment towards the ferry post at Ismailia had also been checked by the artillery. The Turkish rushes stopped 700 yards from the post, and the men dug in.

With this retirement of the reserves the attack really ceased. The assault which was planned near Suez did not develop at all. At Kantara the enemy pushed up to the wire entanglements of the posts north-east of the town, where some of them were captured after dawn, the rest having retired. The Swiffsure shelled this attack across the desert; and so interested was the garrison in watching the shelling, that a force of Turks advanced south-east of the village and was making towards the Canal before attention was called to it. It was then easily stopped on the edge of the low desert scrub. To return to the main attack between Tussum and Serapeum. The enemy remained all day in occupation of the eastern bank. although pinned down by the fire from the western. The Turkish heavy battery opened upon the war ships in Lake Timsah, and two 5.9-in. shells hit the converted merchant-steamer Hardinge of the Indian marine, wrecking one of her funnels. Pilot George Carew, a Cornishman, who was navigating her, had one leg shattered by a shell, but he insisted on remaining on the bridge to advise as to the navigation of the ship to Ismailia. The Turkish battery, before it ceased fire, straddled the Requin with two shells, which fell in the lake on either side of her. At dusk the Turkish field artillery put its last four shells over the Lancashire battery.

The Turkish reserves had retired ; the guns were silent ; but the British higher command was for the time being greatly opposed to committing any troops to an engagement in the desert beyond the Canal, and Geoghegan had gone to the limit of his powers in making his counter-attack. Never was a step more justified than that attack. It put an end to all Turklsh movement near the Canal bank, and cleared an uncertain situation.

When the Indians were withdrawn at the end of that counter-attack, little real touch with the enemy existed. The fighting died down to an active sniping, which was looked upon by Indians and New Zealanders as a game. It was thought at dusk that only snipers remained near the Canal, and that the assaulting troops had retired. As a matter of fact many men from the Turkish supports, who had pluckily reached the Canal bank in the morning, were there still, and not all of them were disposed to surrender. When the battleship Swiftsure came along the Canal on the morning of February 4th, her look-out man was hanging dead over the Crow’s nest, having been sniped from the bank. And when half of the 92nd Punjabis were sent out on the same morning from Serapeum, although a few Turks held up their hands, others behind them refused to recognise the surrender and continued to fire. The Indian force had to be doubled and a second attack made before these, greatly outnumbered and half-surrounded, threw down their arms. Some 250 Turks, with three machine-guns, were taken; 59 others had been killed. Among the dead was a German, Major von den Hagen.

The bank near Tussum had been cleared the day before and the Canal was now free of the enemy. The Turkish trenches near Ismailia and Kantara were found deserted. The Turks had at least temporarily drawn off, and the question arose of striking at them or following them. Some Indian cavalry and infantry were sent forward from the ferry post, Ismailia. About seven miles out the cavalry came upon a body of the enemy estimated at three or four brigades, and another party further north.

The cavalry did not attempt a serious attack.

That evening half a brigade of British Yeomanry reached Ismailia fiom Cairo. On the previous night half of the 2nd Australian Infantry Brigade - the 7th and 8th Battalions and the brigade staff - had also arrived from Mena Camp under Colonel M’Cay. and had bivouacked on the desert near Ismailia station. With these reinforcements to hand, a strong sortie by cavalry and infantry was planned by General Wilson for the next day. A large body of Turkish troops was. how- ever, still at its old camp at Habeita, in the sandhills a few miles from Serapeum, and prisoners said that a strong reinforcement was expected. The British staff had from the first believed that the Tussum attack of February 3rd, in which only some 12,000 Turks had been closely engaged, might be merely preliminary to a much heavier attack by a main army still to arrive. The sortie was therefore abandoned, and the troops remained on the defensive.

On February 7th aeroplanes found the camp at Habeita deserted. The Turkish army had withdrawn into the valleys leading up to the plateau. Along each of the three routes it fast disappeared. Until Djemal Pasha had withdrawn, taking with him along the way he had come his troops, his guns, his animals, and most of his stores, the British staff could scarcely believe that the serious attack, so loudly heralded, had actually come and gone. A sufficient number of Turkish troops remained in Sinai, chiefly at El Arish and Nehkl, to make occasional raids upon the Canal. At the end of March several thousand Turks were found on the central route through Sinai, about 1,000 on the northern route near Kantara, and some 800 near Kubri. The Kantara party managed to smuggle a mine through to the Canal, but their tracks were seen, and the mine found. Another mine was dropped in the desert by a party which nearly reached the Canal at the end of May, and a third was struck by the British steamer Teresias in the Little Bitter Lake on June 30th. On this solitary occasion, for a few hours, the great waterway was blocked. It was, however, continually raided. Once the Turks even waded to a pile-driver moored in the Little Bitter Lake and there captured an Italian. On November 23rd Indian cavalry killed the Bedouin Rizkalla Salim, who had led most of the raids, which thereafter entirely ceased.

Such was the attack on the Suez Canal in 1915.

No Australian regiment was actually engaged in it; it was repulsed mainly by Indian troops. The 7th and 8th Australian Infantry Battalions, some of whose troops had temporarily garrisoned the trenches after the fight, returned to Cairo on February 9th, and the New Zealand Infantry and British Yeomanry about the same time. The Indians on the Canal were gradually drawn upon for Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, and France. The remainder were tied down to strictly defensive warfare, generally on the Canal itself and with a range into the desert of twelve or fifteen miles at most. The Turks could only attack in force during the rainy season, and therefore the only possible serious stroke for the year had been delivered. The apparent timidity of the British command, defending itself behind the Canal and allowing Djemal Pasha with his heavy guns, gear, and animals to withdraw in peace with a hundred miles of pitiless desert behind him, caused much comment in Egypt at the time. But the actual day of the battle was the only one on which a counter-stroke could have been profitably made. When once the enemy was ten miles distant and rested, the chance was gone. Seeing how small was General Wilson’s cavalry force, and how great were the preparations necessary to move even twenty miles into the desert and fight there for a day, it is doubtful if, after the day of battle, he could have done more. The Turks had been heavily beaten, and the British loss was trivial. Against British casualties not exceeding 160 in all, the Turks lost, at a low estimate, 1,600. The losses, indeed, suggested those of a small “native war.” There was a heavy fall in the current estimate of the fighting value of the Turkish Army. This was not without its influence on future events.