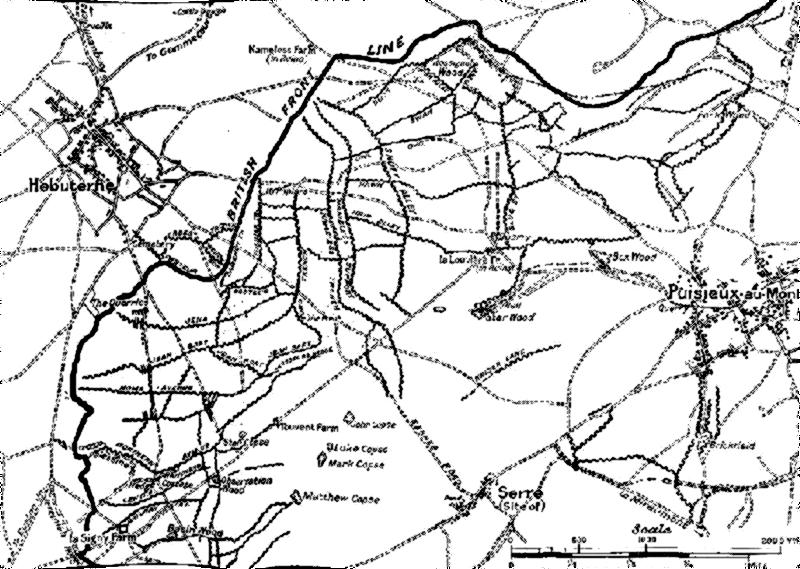

Chapter XXXIII The Raid to Amman

THE capture of the Jordan valley gave Allenby a sound right flank. At the same time it denied to the Turks the use of the Dead Sea and the Wilderness country, and so relieved Jerusalem of any menace from the east. Moreover, it cleared the way for active cooperation with the Arabs. In January, Sherifian troops from the Akaba base had appeared within a few miles of the important Turkish garrison at Maan, where in a number of small engagements they killed several Turks, took many prisoners, and destroyed parts of the railway. These raids compelled the enemy to send down substantial reinforcements from the north, including a battalion of Germans; the Arabs were driven from El Taffel and from other positions which they had occupied, and their offensive was arrested.

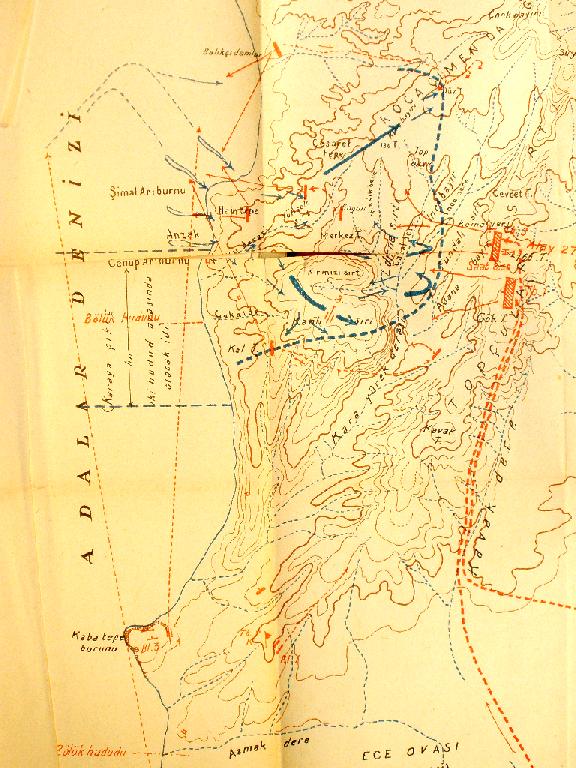

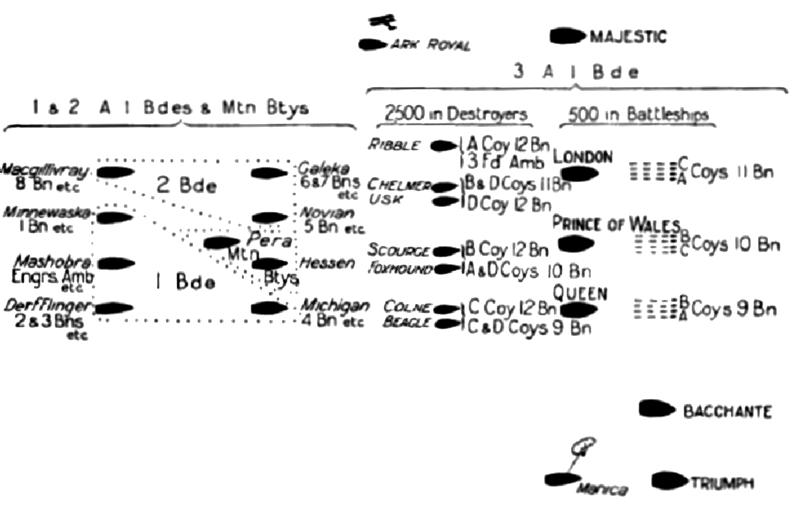

In his struggle against the Arabs, the dependence of the Turk upon the long railway track from Damascus to Medina was absolute. The country, especially to the south, was incapable of supporting considerable forces; and the mounted Arabs, although reluctant to fight at close quarters except when in overwhelming numbers, excelled in raids against isolated Turkish parties away from the railway line. It was, therefore, impossible for the enemy to roam over the land in search of supplies, and all rations, munitions, and equipment had to make the long, slow journey by rail from the north. The Arab aim was to throw the line out of use; again and again they destroyed sections of the track, but the Turks quickly made repairs on the easy, level country, and suffered no permanent disablement; meanwhile they were careful to guard tunnels and viaducts, which would have taken longer to renew, with forces sufficient to keep the Arabs at a distance. At Amman - the Rabbath Ammon of the Old Testament and the Philadelphia of Ptolemy II and the Greeks-the Hejaz railway passed over a long viaduct and through a tunnel, the destruction of which would have held up transport for several weeks. The modern village lies thirty miles east-north east of Jericho in a direct line; although much further by the existing tracks, it was still within raiding distance of Chauvel's mounted troops. During February Allenby decided to make a dash at the position, as soon as the weather cleared, with Anzac Mounted Division and the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Battalions of the Camel Brigade, the Goth Division of infantry being in close support. If successful, the raid would for a time isolate and seriously embarrass the Turks to the south; at worst it would tend to draw the enemy north from Maan, and so ease the task of the Arabs; while in a general way it would unsettle the enemy along the whole British front, and make his High Command uncertain as to where the next heavy blow would fall.

In these and subsequent operations east of the Jordan, Allenby was looking ahead. At this time he had already decided that when he next advanced with his whole army, he would strike with his main strength up the plain of Sharon on the west. It was therefore good policy to show all possible activity on the Jordan side, and this consideration gives a high strategic importance to the fighting in Gilead in March, April, and May. Success at Amman and Es Salt was desirable, but something less than success would serve the Commander-in-Chief's far-sighted purpose.

The enterprise was placed under the command of General Shea, the spirited leader of the 60th Division. "Shea's Group," as the force was called, was supported by a mountain artillery brigade, a heavy battery, and a brigade of armoured cars. His task was stiff and complex. First the infantry had to force the Jordan, in the face of considerable enemy troops concentrated at all the possible crossings. Then, after building bridges (for the Turks had blown LIP the stone bridge at Ghoraniye), it was necessary for the British to climb through steep and narrow passes up the side of Gilead on to the plateau, and after a long march attack what was practically an unknown objective at Amman. With summer conditions and a swift surprise advance, the raid might have been completely successful. But with faulty intelligence, heavy rains in March, the Jordan in high flood and its approaches wet and boggy, every wadi on Gilead running a banker, and the ground on the tableland and around Amman so sodden that mounted work was almost impossible and foot marching very slow-in view of all these obstacles the operation was from the outset unpromising. Worst of all was the compulsory cooperation with the Arabs, which necessitated disclosing to them the British intentions.

As Sherifian activities extended to the north, most of the local tribes gave the Hejaz leaders more or less support. But no tribe could be looked upon as a sure ally. The Arabs throughout played the safe game of waiting for decisive fighting by the British before becoming pronounced in their sympathies and assistance. Round Amman they were in March still friendly to the Turks, and there was no clearly defined line between those who were disposed to join the Hejaz movement and those who were not. News travels rapidly among these nomads, and the British designs, once communicated to the Sherifian leaders, were undoubtedly soon fully known to the Turks. The crossing of the Jordan was delayed for some days by floods; during that time the enemy concentrated around Amman 4,000 troops with fifteen guns and a large number of machine-guns. Trenches were dug, and the approaches to the tunnel and viaduct safeguarded against anything but a sustained assault by a strong force. At the same time the enemy marched 2,000 reinforcements towards Es Salt from the north. A raid which fails to take the enemy by surprise has but a slender chance of success, especially when, as at Amman, the raiding party is operating far away from its base.

About the middle of March the Anzac Mounted Division and the Camel Brigade were gathered about Jerusalem and Bethlehem, as a preliminary to concentration in the neighbourhood of Talat ed Dumm, whence they were to move towards the Jordan. Shea hoped to force the river crossings on the r8th. This adventure proved the greatest of all the many raids carried out by the light horsemen, the New Zealanders, and the Camels; and the story of the march from the Mediterranean seaboard across the maritime plain, over the western and eastern ranges of Palestine, passing on the way Jerusalem. Bethlehem, and the Jordan valley, and ending with hard fighting on the fringe of the Arabian Desert, touches upon every phase of the campaigning life of Allenby's mounted forces.

The progress of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade in the early stages may be taken as typical of the whole. For some time before the Amman exploit Ryrie's regiments had been in camp at their favourite village of Wadi Wanem, down on the Philistine plain. Many of the officers were billeted in Jewish houses. and the horsemen were scattered over the surrounding sand-hills. The closest possible secrecy was observed concerning the operations; but, as usual, every man knew days before the move that some big game was afoot, and intelligent speculation round the camp-fires led to a general belief that the new objective lay across the Jordan. The light horsemen had now in spirit become true soldiers of fortune. They had no longer any expectation of an early end to the war. They had 110 pleasant places in which to spend their occasional periods of leave, for they had tired of Cairo and Port Said. They therefore followed their soldier's life with great heartiness, fighting like devils when they had to fight, and missing none of the little pleasures along the many strange tracks they rode. About the villages they wooed the Jewish girls with great industry but little success, and dabbled heavily, but with much entertainment to the Jews, in many foreign languages. Despite the barriers of blood and speech and faith, the Jews grew fond of these big Australians on their big horses, discovering that beneath their terrible aspect they were gentle and chivalrous young men with a clean, brave outlook and an unfailing respect for all that was good and just in life. On the morning of the 13th. when the three regiments saddled up in the dawn, their lines were thronged with Jewish families, who, aware that fighting was ahead, and exaggerating in their timid minds the horrors of war, shed tears as they bade farewell to their favourite troopers, pressed upon them little parting gifts, and wished them God-speed. Deeply and severely religious as many of these people were, there was something very moving in the blessings they invoked.

Riding past the olive-groves to Ramleh, the light horsemen followed the main road to Latron, a very gay and eager column; for, although heavy fighting might be ahead, they would before that be seeing Jerusalem, and perhaps Bethlehem, and every mind anticipated the crossing of Jordan on the way to the land of Moab. They rode with the strong purpose of old soldiers, but still with the sharp expectancy of happy travellers venturing into a famous land touched with mystery and hallowed by religion, history, and tradition, all more or less familiar to them since their childhood. On either side: of them was the glory of a spring day on the rolling maritime plain, with its thousand crazily-shaped little patches of crops illumined with wild flowers. Overhead was a blue sky flecked with occasional white clouds. Larks sang their sustained song, and in the long column of horsemen there was a note of joy and youth rare in that exhausted old land of suffering and ruins. On the bare slopes behind Latron the brigade halted during a day of strong wind, and parties rambled with enthusiasm over the ruins of the Crusaders' stronghold. At night came heavy rains which, falling for days over all Palestine, delayed the plan of operations, and each hour diminished the prospect of success. The camping-ground became a bog, and every little “bivvy" cunningly built of waterproof sheets was awash. The horses shivered on the swampy lines; the heavily-laden camels, urged on by their wretched, ill-clad, barefooted Egyptian drivers, fumbling and slipping and mutely protesting, were one of the thousand minor tragedies which follow in the wake of war.

In an incessant downpour of rain the brigade rode from Latron to Jerusalem. Every wadi was in flood, the ranges sounded with the noise of rushing waters, and a heavy mist enshrouded the hilltops; but from every sheltered corner in the dripping rocks shone out the wild flowers, the same that had rejoiced the eyes of the Crusaders, and the one touch of softness on the cheerless mountain-side. The three brigades of Anzac Mounted Division were now concentrated about Jerusalem, and the Camel Brigade was at Bethlehem. The 60th Infantry Division was waiting in the Jordan valley and on the hills overlooking Jericho; the mounted Men were within a night's march of Talat ed Dumm all was ready for the attempt to force the crossing. But the Jordan was in high flood (during one night at this time the waters rose seven feet); the swollen current added greatly to the task of building the pontoon bridges; the approaches to the river were sodden and difficult. General Shea was therefore forced to postpone all movement for three days.

This delay, of so much concern to Chaytor-whose Anzac command now included the Camel Brigade, and who was to conduct the mounted operations at Amman-was not unwelcome to the troopers. The men of the and Light Horse Brigade at Jerusalem, and of the Camel Brigade at Bethlehem, were for the first time in the Holy Places; careless of what awaited then1 east of Jordan, they explored the cities with the zest of pilgrims. In all the war the army chaplains out of the firing line were never worked so hard as they were in Palestine, and especially in Jerusalem. The curiosity of the men was boundless; and their diligent reading of the Old and New Testaments, combined with a true reverence, strangely broken by sceptical challenges and even lapses into daring, good-humoured blasphemy, imposed a heavy strain on the physical endurance, the biblical knowledge, and the temper of the regimental padres. From daylight to dark these good men walked the many ways of Christ at the head of successive parties of troopers, who enjoyed nothing so much as "to take a fall" out of their guides. Full of significant suggestion was this spectacle of young Australian light horsemen, led by churchmen in military dress and emu feathers, heavy boots, and clinking spurs, proceeding along the Via Dolorosa or gathered around the traditional Stations of the Cross.

Some of the church services held at this time were deeply moving. The Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem preached a special sermon to the Anzacs at St. George's Cathedral, and all thoughtful men in that congregation reflected upon the strength and glory and endurance of the teaching and life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. Very impressive, too, was a Mass celebrated by Chaplain T. Mullins, of the 5th Light Horse Regiment, one morning in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Sectarianism, that unfortunate intrusion of old-world prejudices into the national life of Australia, did not follow the light horsemen to Palestine. If a padre was a man's man and a soldier of Christian character, few troopers troubled about his particular denomination. Padre Mullins was such to the full, and consequently some 200 officers and men of various churches marched with him to his service at the Holy Sepulchre. The light horseman made no parade of his faith; he rather aimed at concealing it. The senior Australian chaplain in Palestine, the brilliant and witty Chaplain Maitland Woods, once very shrewdly said in a thanksgiving service after victory; " I would describe the light horseman as a man who, while denying he is a Christian, practises all the Christian virtues."

On the night of the 20th the mounted force moved down the Jericho road to camping sites on the rough wilderness about Talat ed Dumm. The Jordan was still in flood, but the rain had passed and the waters were falling. Pains were taken to conceal the horses and camels in the folds between the hills, and special care was exercised in the lighting of fires and in all movement. But these precautions were thrown away; already the Turks were aware of the British plans, not only for the crossing of the river, but for the destruction of the tunnel and viaduct at Amman.

During the 21st, when the Londoners of the 60th Division were concentrated in the Wadi Nueiameh north of Jericho, the enemy reinforced his defences opposite the Ghoraniye crossing with about 600 infantry, and also sent two squadrons of cavalry to the support of his force at the Makhadet Hajla ford further south. With all the fords impassable because of the floods, the Turks might have been expected to deny a passage to the British force. But a river has always been a doubtful barrier in warfare, especially when, as at the Jordan, the attacking army has a choice of bridging sites, and so can deceive the enemy by misleading feints. After careful reconnaissance, Shea had decided to force crossings and throw bridges over the stream at both Ghoraniye and Makhadet Hajla, while strong holding demonstrations were made by minor infantry forces at five summer fords to the north and south.

After nightfall on the 21st, the Londoners stealthily approached the river at the selected points, and about midnight selected swimmers entered the swift current at Ghoraniye and attempted to carry a line to the other side. The stream at the old bridge, even in flood, did not exceed some thirty paces in width. But the waters swept along at nearly seven miles an hour; the banks were fringed with scrub and overhanging trees; and the task was complicated by the frequent bends in the river, which made it very difficult for the swimmers to keep direction. Punts and rafts were also launched, but without success. Many gallant essays were defeated by the current and the darkness; and the Turks, becoming alarmed, opened brisk fire upon the Londoners with rifles and machine-guns. News was then received of a successful crossing at Hajla, and it was decided to abandon for the time the attempt at Ghoraniye.

At Hajla the actual bridging party was made up of "D'' Troop of the 1st Field Squadron Australian Engineers, who were attached to Desert Mounted Corps Headquarters, under the capable leadership of Captain E. J. Howells. A squadron of the 3rd Light Horse Regiment, under Major Dick, acted as a working party to assist in the bridge building, but the driving force of the enterprise was the 23rd Battalion of Londoners, led by Major Craddock, a broker on the London Stock Exchange. Just before midnight a party made up of Sergeant E. S. Claydon, Lance-Corporal R. Strang: Sappers S. Dawson and H. R. Y. McGuigan, and a few Londoners approached the river bearing a raft about 300 lbs. in weight. Dawson volunteered to swim across the rapid, swollen stream with a light line. He was followed into the water by Lieutenant J. W. R. Jones and half-a-dozen others, both British and Australians. The infantrymen swam naked, but carried their rifles. Dawson was first across, and assisted the others to land. At 1.20 am. on the 22nd the first raft, with twenty-seven Londoners, reached the eastern bank. Considerable forces of infantry were at once concentrated on ground covering Howells' engineers and the light horsemen; the material for a pontoon bridge was steadily assembled; at 6 o'clock the construction was begun, and at 7.15 the river was spanned. Meanwhile, the raft was busily employed carrying across small parties of infantry, and at dawn a company was in position on the east bank. Daylight enabled the Turks to open effective fire with machine-guns, and the load on the raft had then to be reduced to eight, the men lying flat on the bottom. Casualties were numerous; of one load of eight Londoners seven were hit. But additional rafts were employed, and before 8 a.m. the 2/19th Battalion of the Londoners had been ferried over; by noon the 2/18th had followed. As the men landed they endeavoured to clear a bridgehead but were strongly resisted by enemy machine gunners on the mud-hills immediately beyond. The work of the bridge builders and the supporting parties was marked by coolness and efficiency, and was distinguished by individual acts of gallantry. Lance-Corporal F. Bell: of the engineers, repeatedly swam down stream under heavy fire, bearing the cables which were to hold the bridge in position. Meanwhile, further attempts to cross at Ghoraniye were beaten off by the enemy fire.

During that night the Auckland Mounted Rifles, who had since the occupation of Jericho been patrolling the west side of the valley, marched to Hajla, and at 4 a.m. on the 23rd the New Zealanders led their horses over the bridge. Riding through the little ring of Londoners they proceeded vigorously to enlarge the bridgehead, and then, moving north, took the Turks in rear at Ghoraniye. The enemy had already decided to yield the river, and were falling back towards the foot-hills about Shunet Nimrin, where the main road from the plain follows the Wadi Shaib in its steep climb to Es Salt. The Aucklands made the most of the position, and, shooting at the gallop from their saddles, killed many Turks; before noon they had captured sixty-eight prisoners and four machine-guns, and cleared the country opposite Ghoraniye. Here the Londoners, renewing their efforts at dawn under cover of heavy machine-gun fire, had succeeded in swimming the river, and bridge building was already in progress. Before nightfall on the 23rd four bridges were completed at the two crossings, and motor-boats, launched on the Dead Sea, were also carrying troops to the eastern side.

Shea's plan was to advance with the infantry by the main road to Es Salt, first seizing the foot-hills on the line Tel el Musta-El Haud on either side of the track above Shunet Nimrin. A mounted force, moving by a rough track to the north, was to endeavour to surprise and capture Es Salt while the infantry pushed up the road. At the same time the other mounted brigades, with the exception of a body which was to hold the Jordan valley to the north, were to climb by various tracks up the mountain side, concentrate on the tableland, and strike swiftly at Amman. The infantry, having gained Es Salt, was to remain there to prevent the enemy from driving in a wedge between Amman and Es Salt on the plateau, and was, if necessary, to send reinforcements to help the horsemen and the Camel Brigade at Amman.

At this stage in the narrative the quality and attitude of the Arabs in the sphere of operations should be considered. As we have seen, the natives north of Maan - where the Hejaz leaders were now operating-had not yet declared definitely for Hussein of Mecca and his fighting sons. It was confidently anticipated, however, that as the Hejaz force moved north these tribesmen - if certain that the British and Arabs were the winning side, and if paid their price in gold, rifles, and munitions - would declare against the Turks. They were therefore to be looked upon by Shea as very friendly neutrals, from whom, with careful handling, much was to be expected. All the British and Dominion troops were ordered to treat them with the utmost respect and consideration. With the exception of Newcombe's party at Asluj, neither General Allenby nor his men had yet had any actual contact with the tribesmen east of the Jordan. They knew the wretched quality of the natives of western Palestine; but, influenced perhaps by tradition rather than Army Intelligence report, they were loath to believe that the bold, proud, fighting Arab of romance was in truth scarcely superior to the lazy, cowardly, and squalid people among whom they had lived and fought during the past two years. It was therefore laid down in orders that "as the general goodwill and assistance to them: east of Jordan is of first importance, all ranks must be warned to treat them with the greatest consideration; all payments are to be made in cash, and all friction is to be strictly avoided. It must be remembered that these natives are of a very different class to those hitherto met with." Troops were also reminded that east of Jordan Arabs were men strong in race-pride, very jealous of their women, quick to take offence, and instant and strong in revenge. This picture of the people served greatly to quicken the interest of the invaders in their enterprise. They felt that they were not only venturing into a strange country rich in historical and religious associations, but about to meet in his home the austere and splendid Arab of the books of their childhood. Unfortunately, still another Holy Land illusion was to he dissipated.

With the bridges complete and free from enemy fire, the way was clear for the advance. On the night of the 23rd Chaytor marched his mounted troops, including the Camel Brigade, down from their bivouacs about Talat ed Dumm and Nebi Musa, and towards the morning all four bridges were clattering under the shod horses. The night in the valley was fine and warm, with bright moonlight, and the force was in perfect physical condition and keen for the adventure. As the regiments waited their turn to cross, hundreds of troopers threw themselves on the ground, and almost instantly were sleeping soundly; others, with a fine disregard for what the future might bring, gathered into groups, boiled their "quarts" in the shelter of the broken ground, and made an extra meal of little luxuries carried down on the saddles from the army canteens at Jerusalem. Among these old campaigners there was no evidence of high tension.

The first light horsemen to cross the river were the troops of the 6th Regiment at Hajla, under Lieutenant-Colonel Fuller, who had rejoined his regiment a few hours earlier, after a brief spell of leave in Australia. The rest of the 2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade followed, and Fuller's Regiment was sent forward at dawn to seize the foot-hills about Teleil Muslim as speedily as possible. The three brigades of the 60th Division were already across, and the Canterbury and Wellington Regiments, with the headquarters of the New Zealand Brigade, the Camel Brigade, and Cox's 1st Light Horse Brigade, made the east side during the morning. While Ryrie followed the 6th Regiment due east, Cox was pushed up the valley to the north, his mission being to locate the track leading to Es Salt from the Umm esh Shert crossing of the Jordan, and to occupy a line which would cover it from the north. One squadron of the 3rd Regiment was opposed by about 150 enemy cavalry, who after a brief encounter retired over the river to the west by the Umm esh Shert crossing. On the right, Cox made touch with the Londoners, who were advancing on the high hill El Haud north of the Es Salt road.

Advancing due east across the valley, Ryrie's 2nd Brigade met with no opposition, though a single enemy shell was fired at them, and except at a considerable distance no Turks were seen until Amman was reached three days later. The two sides of the valley present a remarkable contrast in fertility. On the west the plain is a desert waste with no traces of cultivation. But, as the light horsemen cleared the mud-hills on the east, they rode into a wide area of flourishing crops of bearded wheat in full head. Careful not to offend the native owners, the horsemen followed narrow footpaths through the grain, and resisted the temptation to jump off and pull sheaves for their hungry horses. Suddenly a great shouting was heard, and a swarm of men and boys mounted on Arab ponies of many colours came galloping, careless of damage, across the growing wheat. In the distance they were picturesque and imposing and expectation ran high. Here at last, thought the Australians, were the superior men of the east of Jordan, the true Arabs of Arabia. They raced down, shouting, and waving their rifles, and in flowing dress of many hues made a gallant show against the green countryside. Seeking the Australian leader, they reined up their Arab steeds in a clamorous throng round Ryrie and his staff. At close range they were a strange, motley lot of warriors. Physically beautiful men, with an easy, graceful carriage, they rode miserable skinny, little ponies, greys and bays and chestnuts, some with rich saddles and trappings, but most of them with the leather in tatters. Many of the wretched ponies bore two splendid men; or an Arab with the native majesty of a Saladin, clad in robes of silk and with a great sword at his side and a richly jewelled dagger in his belt, would be astride an emaciated pony, his feet in rusted stirrup-irons attached to the saddle with pieces of rope. In the mass they seemed some strange circus caught in all its soiled bravery in the pitiless light of sunrise. They knew no leader, and, when asked questions by the brigade interpreter, all talked in chorus. But if in appearance they were unconvincing as soldiers, they were demonstrative in their welcome, and seemed very anxious to serve the British interest. After a brief parley in the grain, they rode with Ryrie towards the foot-hills. On the way they pointed out two badly wounded Turks, victims of the charge of the Aucklands on the previous day. These wretched, bleeding men, fretting in a long agony, had worn dusty patches in the green grass; but they excited only the derision of the Arabs, who had done nothing to give them relief, and who showed surprise when the brigade-major called up his interpreter and told the one still conscious Turk that stretcher-bearers would be summoned, and they would at once receive treatment. Near Salha a large Arab encampment was reached, where, despite Ryrie's protests against delay, the Arab sheikh insisted upon entertaining him arid some members of his staff to coffee in a huge, black goat-hair tent, decked with barbarous Manchester cottons. A little further on the regiments halted for breakfast in the foot-hills, where the deep, rich grasses were very welcome to the horses. At about 11 a.m. a few hundred enemy cavalry were seen on the hills to the east, and Ryrie rode forward at the gallop with the 6th Regiment in an attempt to cut off and envelop them. But the intervening country was broken into a hundred stony hills and deep narrow wadis, and the Turks made a leisurely escape. During this movement glimpses were seen of a long enemy camel-train, moving across the Australian front towards the north: it seemed as if the Turks were concentrating the forces which had been scattered between Amman and Maan. SO as to prevent their isolation and capture.

Meanwhile, the New Zealanders had been pushing on in the face of desultory shell-fire towards Shunet Nimrin, whence they were to climb the mountains by the track leading up to Ain es Sir. At 3 p.m., Ryrie, having re-assembled his brigade, marched towards Ain el Hekr by the track south of the New Zealand route. The intelligence as to the state of the tracks proved misleading. Ryrie's route was said to be fit for wheels, and the brigade was in consequence accompanied by its Royal Horse battery and a number of limbers, while behind followed another battery with Anzac Divisional Headquarters, and more limbers carrying the explosives for demolishing the railway works. After leaving the foot-hills the track ascended rapidly, winding tortuously round the beds of narrow, rocky wadis. The foot-hills were scarcely cleared before the guns and limbers were in difficulty; after four miles the path narrowed down to passages between rocks impassable for wheels and difficult even for led horses. After a rapid reconnaissance in the gathering darkness, Ryrie was compelled to advise Chaytor that the batteries and other vehicles must be left behind, and Chaytor agreed. This imposed a delay of some hours while the explosives were being taken from the limbers and placed on camels. At 9.30 p.m., when the march was resumed, the pace became very slow, as the horsemen were obliged to ride only two abreast. and often to lead their horses in single file through the rocky defiles. Behind Divisional Headquarters came Smith's Camel Brigade, and the column was by midnight spread out over many miles in enemy country almost totally unknown, and dependent for guidance upon friendly but nervous Arabs, while the steep, broken ranges on either side of the confined track made the employment of flank-guards extremely difficult.

A blow at the column with machine-guns in the night must have led to confusion; but the Turks had apparently gone right back to Amman, and offered no opposition. At 2 a.m. on the 25th. rain began to fall heavily. The hillsides were already soaked with water, soon the wadis were flooded, and the sloping track and patches of flat rock gave but a precarious foothold to the horses. The night turned bitterly cold. Within an hour most of the men were drenched. But the climb, with the 6th Light Horse as advance-guard, was steadily maintained. Working parties with shovels accompanied the leading squadron, and strove hard to improve the worst patches, but still the whole brigade was at times reduced to leading the horses in single file.

The ascent of the light horsemen, however, was an easy task compared with the terrible climb of the Camel Brigade.

Immediately after leaving the foot-hills General Smith was obliged to dismount his force, and all night the men of the three battalions dragged their camels up the mountain-side. The men hauled and urged; the camels slipped and fell, but still fought steadily on. The brigade straggled in single file almost from the valley to the plateau, winding its fantastic course along crooked and flooded wadi beds, and treading narrow ledges round the sides of the hills. Jn peace time such a feat would have been deemed impossible by any Eastern master of caravanning; but under the brutal lash of war the brigade went surely up to the tableland. " The camels were carried up by the men," said Smith next day. No less fine was the performance of the Egyptian drivers with the pack camels which carried supplies and explosives.

Ain el Hekr, on the edge of the plateau, was reached by the head of the 2nd Brigade about 4 a.m., and Ryrie, having established outposts, halted there in a narrow, rocky gorge to wait for daylight. Dawn disclosed the brigade drenched and covered with mud, in a valley leading out on to the treeless tableland. Heavy rain was falling: much of the country was under a few inches of water, and little streams gushed from every rocky outcrop. But the spirits of the men, now twa nights without sleep, were still high. They jested about their sodden clothes and chilled bodies; with a resource almost miraculous they quickly lit hundreds of little fires with wood which, with the foresight of veterans, they had carried up from the plain below.

However stern and exciting the operation, the light horseman never forgot his horse or his fire. While camped at Talat ed Dumm waiting for the advance, men had walked many miles along the steep, narrow wadis gathering occasional plants of wild barley, content if after hours of climbing and searching they returned with a green feed for their horses. One morning, as they rode towards Amman, they came upon two or three old Turkish telegraph poles. In a few minutes, without any halt to the column, the poles had been pulled down, hacked to pieces with bayonets, and tied up into little bundles of firewood on a hundred saddles.

At Ain el Hekr the head of the column was within a few hours' march of Amman, but the Camel Brigade was still far down the mountain-side. Smith joined Ryrie on the morning of the 25th, but the day had almost passed before the last of his three battalions reached the plateau. Heavy wind-driven showers fell frequently, and, coupled with the floods, made rest impossible. A large Bedouin encampment provided a few lucky light horsemen with eggs and camel whey, but most of the men were confined to their rations. They had ridden from the valley with one day's supply on their saddles and two on the pack-camels, which had not yet arrived. Already the "iron" rations were being eaten, and the position was giving concern to Chaytor. The Camels, however, were as usual rich in foodstuffs, having three or four days' supply with them; and it was decided to divide these with the me11 of Ryrie's brigade.

At 7.30 p.m. on the 25th, Chaytor resumed his march with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the Camels. The track was flooded and rocky; heavy showers fell frequently, and the night was piercingly cold. The camels, floundering in the mud, moved very slowly, and the light horsemen had of necessity to conform to their pace. Marching first through Naaur - one of the many Circassian villages planted by the Turks in eastern Palestine as a standing check to the lawlessness of the Arab tribes - the column turned north towards Ain es Sir. The Circassians were, as had been expected, very friendly to the Turks and hostile to the raiders, and at Naaur Captain Suttor, of the 7th Regiment, caught three men signalling with lights. There was, however, still no sign of the Turks. The route was indefinite, and as the force was now close to Amman, the advance-guard of the 7th Regiment, which was leading, moved very cautiously. Halts were frequent; so exhausted were the men that each time, as they dismounted, they would drop exhausted on clumps of wet bushes beside the track, and fall instantly into heavy sleep. And all night, as the brigade crept along, fast-walking horses with men asleep in the saddles would break from the sections and pace up towards the head of the column, until a friendly hand caught their bridles and awakened their stupefied riders.

Just before dawn the head of the column met the New Zealanders encamped at the cross-roads one mile east of Ain es Sir, where without serious fighting they had captured a party of ninety Turks. Meldrum's brigade had found their track easier than that followed by the Australians, but still too rough for guns and limbers. From Ain es Sir the 2nd Brigade moved a few miles north to Birket um Amud. Chaytor's orders were to move on Amman as soon as his concentration was complete on the tableland. But his men had now. been three days and nights without rest, and had passed through a great physical strain. He decided, therefore, to delay the attack for twenty-four hours; and, as the day was fine, the men pitched their "bivvies" and dried their clothes, and, with the exception of those on outpost, were refreshed by sleep.

As the 2nd Brigade was settling down, one of the patrols observed an enemy motor-convoy on the Amman-Es Salt road. Major Bolingbroke, who, in the absence of Cameron on leave in England, was leading the 5th Regiment, was at once ordered to attack with two squadrons. The convoy was quickly enveloped, but not before fifty Turks on a ridge behind had escaped. The Australians took twelve prisoners and found nineteen motor-lorries, three motor-cars, an armoured car, and a number of other vehicles stuck in the mud of the new road. The Germans had damaged the engines of the motors to prevent their removal, and the Bedouins had stripped them of all that was loose. The incident impressed on Chaytor the fact that the enemy was fully aware of the British intentions against Amman; and the ride of Bolingbroke's men over the boggy ground indicated that in the fighting ahead all movement would be desperately slow. Patrols of the 6th Regiment towards the village of Suweile surrounded and captured sixty-one Turks without serious fighting.

Some railway engines and rolling stock were believed to be at Amman; to prevent their escape, Chaytor on the night of the 26th ordered the line to be cut north and south of the station. A party from the New Zealand Brigade succeeded in destroying a section seven miles to the south, but a squadron of the 5th Light Horse Regiment, engaged on a similar mission to the north, were prevented by enemy cavalry from reaching the railroad.

When, on the morning of the 27th, Chaytor ordered the advance on Amman he had in his two mounted brigades and the Camel Brigade a force of some 3,000 rifles for the firing line, supported by the single mountain battery of 18-pounders attached to the Camels. The Turks held Amman with about 4,000 troops in' carefully prepared positions; they had fifteen guns, and were strong in machine-guns. The position was almost ideal for defence. The railway ran roughly north and south, passing about one and a half miles east of the settlement. Immediately between Amman and the line was a group of high, rough ranges culminating in Hill 3039, and at the foot of this knoll, beside the Wadi Amman, was the modern village. The ruins of the ancient Roman city, including the magnificent theatre and the Street of Columns. are the finest to be found east of Jordan. Immediately north of the settlement is the old Roman citadel, made up of three substantial stone terraces and a tower, all still sound and formidable for defence. The wadi, deep and rugged, with many little tributaries joining it close to Amman, flowed eastwards towards the village and then turned north along the railway. Less than two miles south-east of the village, in very rough, mountainous country, lay the stone viaduct and the tunnel which were the British objectives.

Chaytor's three brigades advanced across a number of wide, shallow valleys divided by ridges with stony outcrops. From the last of these ridges they looked down a long slope torn by many water-courses, with intervening patches of boggy, cultivated land, to the foot of the dark hills which rise sharply behind the village. But so rugged was the ground that no glimpse could be had of the village itself. Intelligence was vague, the maps supplied were inexact, and when the attack was launched the whole position was ominously obscure. Outnumbered, sinking deep at every stride in the spongy ground, and unsupported by artillery, the mounted brigades moved steadily towards their invisible foe.

Even before the brigades reached the last crest and dismounted, the Turks from their heights across the wadi had a complete view of the advance. Their guns had been registered on every path by which the British must come, and their machine-guns were placed so as to sweep the whole area. The New Zealanders were directed across the Wadi Amman on the right, where from the south they were to attack the hill frontage between Amman village and the railway station. The 1st (Australian) and 2nd (British) Battalions of Camels, with their superior numbers, were to make a direct frontal blow at the village in the centre. Ryrie's brigade was to attempt an enveloping movement north of the village, on the left of the Camel Brigade. As the brigades rode into range of the enemy's guns they were lightly shelled; but it was clear, as it had been on the ride up the range, that the Turk was well satisfied with his position and disposed to let the raiders come to close quarters. On the right the New Zealanders were hotly opposed with machine-gun fire. They found the deep bed of the Wadi Amman almost impassable, and were forced to lead their horses in single file, so that it was 3 p.m. before they were ready for the assault. While, therefore, the Camels and Australian Light Horse Brigade advanced resolutely in the centre and on the left, the enemy was not on the first day seriously menaced, as Chaytor had hoped, by the New Zealanders' thrust on the right.

Advance on Amman, 27th March, 1918.

Leaving their horses behind the last of the ridges, about a mile and a half from Amman, the 6th and 7th Regiments of Ryrie's brigade advanced down the boggy slope. The 7th moved directly on the village, with a squadron of the 6th on its left, while the remaining two squadrons of the 6th were put in with the machine-gun squadron, which was pushed forward over very broken ground between the 7th and the Camel Brigade. Marching in extended order on a front of about a mile, the light horse squadrons trudged steadily over the heavy ground, a striking picture of serene courage engaged in a desperate and hopeless mission. Not a Turk was visible: except for a little shelling, there was a sinister silence about the dark, broken base of the steep, bare hills ahead. Had the enemy been only a few hundred strong, he could have beaten the attacking forces off with rifle-fire alone; in his thousands, and with guns and machine-guns, he could destroy every Australian, if the attack were pressed home. For a time, however, the Turks held their fire, and the light horsemen covered three-quarters of a mile almost without casualties. Then, as if in instant response to a single order, guns, machine-guns, and rifles opened fire together, with a roar and a rattle which echoed and re-echoed from the hills and wadis that covered them. The Australians, although falling thickly, pressed gamely on until some of them were within six hundred yards of the place where they believed the invisible village to be located. But as the enemy corrected his range the deluge of shells and hail of bullets became annihilating in intensity, and the advancing lines were forced to take to the ground for cover. For a time they held on; but they had no targets, their losses continued heavy, and further advance was impossible; they were therefore withdrawn to positions of relative safety. On the right of the brigade the progress of the machine-gun squadron, under Captain Cain, and the two squadrons of the 6th Regiment had for a time been promising. Cain with his machine-guns was able to reach an old stone house on a patch of high ground looking down on the main wadi near Amman, and covering the front of the light horsemen who were attacking on the left. The gunners found good targets; but the enemy had no difficulty in stopping the march of the men of the 6th, and there, too, the attack failed decisively. Further to the right the 2nd Battalion of the Camels made a gallant and spectacular advance across a number of little bare fields surrounded by stone fences. Marching in successive waves with perfect steadiness under a heavy shrapnel barrage, the men penetrated as far as the main wadi before they were stopped by blinding machine-gun fire at close range from concealed positions. On the right the effort of the Canterbury and Auckland Regiments of the New Zealand Brigade was not made until the attack by the light horsemen and Camels was spent. The country before Meldrum's men was exceedingly rough, and they were soon brought to a standstill. Shortly before dark the Turks stoutly counterattacked the Canterburys and drove them from their line; but the Canterburys, rallying with the bayonet, regained the ground and held it during the night.

The 4th Battalion of the Camel Brigade (Australian and New Zealand), under Lieutenant-Colonel A. J. Mills, had been sent round beyond the New Zealanders on to the railway south-east of Amman, and at once began a systematic destruction of the line. In this work they were assisted by the Wellington Regiment, and several miles of rails were broken up with explosives That night Chaytor ordered the 2nd Light Horse Brigade to make a second attempt to cut the railway to the north. Bolingbroke, of the 911, marching in the darkness with two squadrons over very rough country, reached the railway about 7 miles from Amman There a two-span stone bridge about thirty feet long was reached-a good example of marching on the compass--and completely wrecked by Lieutenant H. A. Lockington, of the New Zealand Engineers. After an absence of seven hours, the party returned to the brigade at 5 a.m. on the 28th. Amman was now temporarily isolated; but the first day's fighting had convinced Chaytor that the position could not be reduced by his slender mounted force alone. Already there had been over 200 casualties, and, although a few Turks had been captured, the enemy position had not been in the least shaken. While the mounted force was climbing up to the plateau by the tracks to the south, Es Salt had been won without fighting by the 3rd Light Horse Regiment under Bell, and the 60th Division quickly followed by the main road. On March 25th Cox had renewed his activity along the eastern side of the Jordan valley. The 3rd Regiment in the foot-hills on the right made touch with the infantry towards El Haud. while the 2nd under Bourne crossed the track leading over the plain from Umm esh Shert to Es Salt, and held it against an enemy advance down the plain from the north. Bell, his left flank thus assured, struck up the range for Es Salt. He was to advance on the town as rapidly as possible; but the track, which, as it left the plain, was only located with difficulty, proved particularly rough and steep. In places it ran over naked, flat rock on a sharp gradient, and for three miles the men were compelled to lead their horses. But Bell, one of the most aggressive and astute leaders produced by the light horse, was a happy selection for the mission. Urging on his advance-guard and, as the enterprise demanded, taking all risks, he rode hard for Es Salt. The Turks, startled at the swiftness of his approach-which menaced the communications of the troops which they had opposed to the infantry on the road from Shunet Nimrin-withdrew without fighting. Es Salt is a dark, crowded, mountain-built old town of 15,000 inhabitants. Of these about 4,000 are Christians, who, living isolated among the fanatical Arabs of eastern Palestine, were during the war even more fearful of massacre than were the Christians of western Palestine. As Bell's men rode into the narrow streets, these hapless people were for a time too surprised and incredulous to be demonstrative. But as the Australians cleared the town of the Turkish stragglers, and pushed out covering patrols, and as the infantry battalions marched in a few hours later, they saw in this dramatic intervention their deliverance from the sinister shadow of Moslem rule and from the desert raiders, and their satisfaction and joy were immeasurable.

Even before the attack at Amman began, Shea doubted the capacity of Chaytor's three mounted brigades to achieve the objects of the raid. It was inevitable that the delay of nearly a week must have greatly reduced the chance of a surprise and a quick, decisive action. He therefore ordered a battalion of the 181st Brigade to march from Es Salt for Amman at dawn on the morning of the 27th, when Chaytor was to make his first assault. This battalion was unfortunately delayed by a tribal brawl along the road between the Circassians of Suweile and the Christian Arabs of El Fuheis, in which there was much shooting and picturesque demonstration at harmless ranges. The two remaining battalions of the 181st Brigade were then ordered forward to Amman; marching by night, their advance-guards made touch with the Australians early in the morning of the 28th. Chaytor decided to renew the assault early in the afternoon. The 4th Battalion of the Camel Brigade was then on the extreme right, astride the railway, about a mile and a half from Kusr es Seba; the New Zealand Brigade carried the line north-west to within about 1,000 yards of Amman; on the left of the New Zealanders were the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Camel Brigade, with the 2/23rd and 2/21st Londoners on their left; while on the left flank was Ryrie's brigade, covering a front of one and a half miles. The mountain batteries accompanied the infantry from Es Salt, but although they opened fire promptly and did useful shooting on Hill 3039, their metal was too light to have any demoralising effect upon the hidden enemy. Soon after the arrival of the infantry, Chaytor ordered a mounted dash by the two horse brigades for a position north of the town, while the infantry and the Camels made a frontal attack from the south. This, however, was immediately cancelled, and a general dismounted assault was decided upon. The Turks were fully conscious of their strength in numbers and position, and throughout the engagement seized every opportunity to counter-attack. Soon after noon, when the British were deploying for the assault, they fell heavily on the line at the junction between the New Zealanders and the Camels, but after reaching within bombing distance, they were checked with severe losses.

The Londoners had been marching all night over terrible roads; but, when at I p.m. the assault was commenced, they dashed forward with so much spirit, and were so speedily lost to view in the folds of the broken ground, that for the moment it appeared as if their weight on a narrow front might prevail. At the same time the 1st and 2nd Camel Battalions drove in strongly on their right, and the New Zealanders pressed vigorously for the dominating Hill 3039. But the promise of achievement was short-lived. As the half circle converged upon Amman, the troops came under a devastating fire from all arms, and the vigour of their advance was destroyed by sheer casualties. Mills, with the 4th Camel Battalion on the right, and the New Zealanders were arrested by hidden nests of machine-gunners on Hill 3039; the 1st and 2nd Camel Battalions were cut down as they reached the broken ground about the main wadi, and could make no headway until the hill was cleared; while the infantry, who were more exposed, and whose line was shortening and presenting an improving target, were shot to a standstill by the unseen foe.

As the attack developed, two squadrons of the 5th Australian Light Horse Regiment made a mounted dash down a large wadi between the Camel Brigade and the infantry. They rapidly covered half-a-mile; but, after dismounting, their attempt was halted by machine-gun fire, while their horses suffered many casualties from the enemy's shells. '

Meanwhile, out on the extreme left flank the fight had been, going badly with Ryrie's 6th and 7th Regiments. The light horsemen, with the 7th on the right next to the infantry, moved off in two lines down a slope covered with patches of young barley, and bearing on an enemy aerodrome in the direction of the Amman railway station. For nearly a mile the men pressed steadily on in the face of heavy machine-gun and rifle fire and light shrapnel. The 7th under Onslow reached a valley faced by a steep ridge, which was held by Turks in a series of stone sangars. On their left the ground rose sharply to a stony ridge which had been gained by a squadron of the 6th under Major H. S. Ryrie. This squadron was only fifty-eight strong when the advance began, and the others were correspondingly weak. Before reaching the ridge Ryrie, a dashing soldier, was severely wounded in the head, and the command was taken over by Lieutenant H. Dickson. From the ridge gained by Dickson's men the ground fell sharply into a narrow gully, and then rose steeply to the ridge occupied by Turks in sangars. Onslow, who was directing both regiments, ordered an attack on the ridge. Dickson at once reported that, as he was being heavily enfiladed from the open flank on his left, and strongly held in front, the prospect of success was small. The order was repeated; the line of the 7th on his right moved forward, and Dickson dashed over the crest with three troops. Wounded at once, he handed over the command to Lieutenant F. L. Ridgway, who, followed by his men, made an heroic rush down the slope. The three troops were instantly caught in bursts of machine-gun fire from the front and the left flank; many men fell before they cleared the crest, and of those who went down into the valley only one man, wounded in four places, regained the Australian lines.

The 7th, supported by one troop of Major Ryrie's squadron, moving on the low ground on the right, were stopped at once by the intensity of the fire, and Onslow, seeing the position was grave, ordered a general retirement. Then the Turks, always quick to counter-attack, left their sangars and rushed shouting down the XI. The light horse casualties had been heavy; of the fifty-eight men in Ryrie's squadron of the 6th, forty were killed, wounded, or missing, and the 7th had also been severely handled. For a moment the outlook was critical; but with that coolness and straight shooting which always distinguished the light horsemen at the blackest stages of a fight, the retreating line was at once organised, and, with the assistance of a machine-gun and Hotchkiss guns, the enemy was checked and held while the wounded, except those of the 6th who had crossed the ridge, were carried back to safety. The retirement was then continued for a few hundred yards until a sound defensive line was reached. During the two days the 6th and 7th had suffered severely in both officers and men. Of the officers in the 6th Majors Ryrie and Cross, and Lieutenants G. V. Evans:' H. G. Lomax, A. B. Campbell, and H. Dickson were wounded, while Ridgway (who, as was afterwards learned, had been killed) was missing; in the 7th Major Barton, Captain Suttor, and Lieutenant Finlay were wounded.

When night fell, and Shea was able to survey his whole position east of Jordan, the situation was anything but promising. At Amman the only compensation for two days' heavy fighting and severe losses was the demolition of upwards of five miles of railway on the right. The track destroyed, however, was on the level, and though all the rails were broken its repair would not be a serious task for the Turks. Large bodies of fierce-looking Arabs had swarmed about the various British headquarters and had made eager offers of assistance. Their main purpose, however, was to secure gifts of ammunition for their rifles, and, as Chaytor's supplies were already desperately short, there was little to give to these doubtful allies. One party of about 500 were asked to watch the broken railway bridge to the north, and moved off with apparent joy on their mission. Yet the bridge was repaired, and the Turks on the morning of the 29th brought down a train with reinforcements to Amman station. To the south another body about 1,000strong volunteered to keep the enemy away from Mills; but on the approach of the Turks they faded off, and the Australians had at times to fight hard to protect their demolition parties. Of another Arab body, which volunteered to watch General Ryrie's exposed left flank, one or two rushed shouting on to the skyline, fired off their rifles in the air, and then ran for their lives. When they were not begging ammunition, they were preying on scraps of food thrown to them by the scornful but amused Anzacs, and cleaning out discarded jam and bully beef tins with their forefingers. A smiling, childlike host, they seemed to look upon the desperate business as a comedy staged for their entertainment.

Not only at Amman was the situation disquieting.

The enemy had brought substantial reinforcements across the Jordan at Jisr ed Damieh by the road which leads from Nablus to Es Salt. He was pushing strongly down the valley against the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Regiments of Cox's brigade, and at Es Salt was bringing pressure on the infantry and Bell's 3rd Light Horse Regiment. There was a strong possibility that he might penetrate even as far as the Dead Sea, and so cut the British communications and isolate the large force in the hills and on the plateau.

Intelligence, which was bad throughout the operation. indicated that the enemy contemplated the evacuation of Amman, and Shea ordered Chaytor to persist with his attack.

Nor was Chaytor yet disposed to accept failure. On the evening of the 28th two additional battalions of infantry from Es Salt joined the Amman force, and it was decided to renew the assault early on the following morning. The Londoners, however, were exhausted after their long trudge in the mud; as arrangements for the morning attack would have kept them working through the night, Chaytor decided to postpone it, and to make an attempt upon the position in the darkness of the night of the 29th. A battery of Royal Horse Artillery was ordered up from Shunet Nimrin for this assault.

Throughout the night of the 28th and the day of the 29th the enemy freely shelled Chaytor's positions. The British mountain batteries, outranged and throwing only light shells, or at times without ammunition, were of some moral support to the British, but were never able seriously to trouble the 'Turkish garrison. Shea had looked for the British airmen to cooperate by bombing the enemy. The heavy rains and mists on the highlands, however, hampered operations in the air, and two forces of aeroplanes which were sent out missed Amman and bombed villages to the north and south. After the failure on the 28th the Turks made persistent attempts to work round Ryrie's exposed left flank. The light horse regiments were reduced by casualties and the employment of men on patrol and other duties. On the night of the 28th the 7th Regiment was able to put only fifty men in the firing line, and, as the front was repeatedly extended to prevent the enemy's outflanking movement, the brigade became so strung out that it was unable to take any further part in the actual attack.

Shea's order to Chaytor for the operations of the night 29-30th was peremptory. Amman must be taken. In deciding on the night assault Chaytor had the support of all officers on the spot who had engaged the enemy at close quarters. The two daylight attempts had made them familiar with the ground, and they believed that a swift advance in the darkness, when the effective use of artillery and machine-guns would be denied to the enemy, had a fair chance of success. The order of the advance was almost identical with that of the 28th. The New Zealanders, with Mills' Camel battalion on their right, the Camel brigade, and the infantry were to concentrate upon Hill 3039, Amman village, and Amman station; while the 2nd Light Horse Brigade was to distract the Turks by a demonstration on the left.

Rain, driven by strong and biting winds, had fallen at intervals all through the operations, and each morning the water on the bleak countryside had been sheeted with ice. Constantly wet and cold, the men had suffered acutely, while the boggy ground made all movement very exhausting. Happily the supply of rations, although on a slender scale, had been regular. Each night the faithful Egyptian drivers had arrived with their long trains of patient camels; the Australians never perhaps so deeply appreciated the genius and driving force behind the British Army transport service as when, night after night, some sixty miles from railhead at Jerusalem station, they drew their allowance of cheering rum. The night of the 29th was dark, wet, and intensely cold, and despite the desperate nature of the enterprise, all ranks as they shivered in the wind prayed for the order to move. Soon after 2 a.m. on the 30th the advance was begun, and the irregular line, with many gaps caused by wadis and steep ridges, crept forward with bomb and bayonet. For a time they were not discovered; but at 3.10 a.m. heavy rifle and machine-gun fire broke out in front of the infantry, and soon became general along the intricate winding bed of the main wadi and on the dark heights beyond.

It was believed that, if early in the fight the New Zealanders could win Hill 3039, the infantry and Camels could carry the whole position, and Meldrum's men pressed towards their objective with all their customary resolution. Working towards the top of the hill from the rear, they captured the higher trenches first at about 4.30 a.m., and at dawn easily compelled the surrender of the line of earthworks lower down, where they took prisoners and six machine-guns. But they were unable to occupy the whole of the hill, and about 9.30 a.m. were strongly assaulted by successive waves of Turks, who charged to within ten yards of the New Zealand riflemen. Mills, however, was now, after a hard-fighting advance, close up on the right, and the New Zealanders and Camels. rising with the bayonet, dashed at the enemy and swept them from the hillside The New Zealanders suffered sharp losses, among the killed being Lieutenant S. Berryman, while Captain H. B. Hinson and Lieutenant H. Benson were mortally wounded. Shortly before this a detachment of New Zealanders had penetrated the village, but were at once fired upon from the houses, and, being isolated, were forced to withdraw.

Success had been only piecemeal. The two Camel battalions in the centre, attacking with hand-grenades, had quickly rushed the two enemy trenches which were their immediate objective; but they then found themselves in advance of the New Zealanders on their right and the infantry on their left, and came under heavy enfilade fire from both flanks. Lieutenant F. Matthews with a small party of Australians dashed on beyond the trenches and, like the New Zealanders, entered the village, but was almost at once driven out. The captured trenches were consolidated, but further progress was checked by fire from the part of Hill 3039 still held by the enemy, and from the old citadel to the left.

The infantry also had initial successes.

In their first sweep before dawn they overran forward trenches and sangars, and captured 135 prisoners and four machine-guns. But even in the darkness the Turkish machine-gun and rifle fire, registered on the converging front of the British attack, was very effective. Chaytor found at daylight that the assault had nowhere been decisive; hi5 men were everywhere exposed to fearful punishment at a range of only a few hundred yards. The New Zealanders were pinned down to the western end of Hill 3039, and hotly counter-attacked. The Camels were under heavy enfilade fire from both flanks, while the Turks, advancing boldly on the left of the infantry, drove the British back. Rallying finely, the Londoners returned with the bayonet and regained the lost ground. But the Turks were firm on their old positions, while everywhere the British were exhausted by their supreme endeavour over the soft, slimy ground, and were sorely reduced by casualties. By 10 a.m. it was plain that the assault had failed.

On the extreme right a stout advance had been made by Australians of the 4th Camel Battalion under Mills. Striking in between Hill 3039 and the railway, they rushed three ridges in the darkness, but were then soundly held. Daylight found them lying out in an exposed position, with only scattered rocks to protect them from a deluge of high explosive and shrapnel. During the day the Turks launched a determined counter-attack: but this was checked by a party which Mills sent out on the right, whence a cross-fire was brought to bear on the enemy's infantry. On Hill 3039 the New Zealanders were again assailed, but, adding to their own fire that of the captured machine-guns, they maintained their ground. The whole position was now serious, as one break in the erratic

Amman during Turkish counter-attack on Hill 3039 on 30th March, 1918.

British line might have led to disaster. But the chief menace to Chaytor's force was on the left, where the enemy increased his efforts to work round Ryrie's weak flank, and so cut across the communications with Es Salt. As a last throw, a company of Londoners, which had been in reserve, was ordered at 2 p.m. to attack the citadel north of the village; but this little force was caught by machine-gun fire from both flanks, and the effort was abandoned.

Soon afterwards Shea, who was at Es Salt, asked Chaytor if he considered Amman could be taken that day. The New Zealander replied with an emphatic negative. Shea then ordered the abandonment of the attempt on the tunnel and viaduct, and the withdrawal of the force. The decision was inevitable. Shea had sent to Amman every man who could be spared from Es Salt. Chaytor had handled his brigades with fine tactical skill. 'The brigade work had been good, and the regimental and battalion leadership, all in the hands of officers of long experience, had been magnificent. Every man had fought with complete confidence in both Shea and Chaytor, who were looked upon as the first divisional leaders of infantry and mounted troops in the British army in Palestine. The Turks had won, and won decisively, by their superior numbers and their position of extraordinary natural strength.

Had the Turks made a general counter-attack on the day or night of the 30th, Chaytor's withdrawal must have been extremely hazardous; but, except for sporadic advances, they remained on their ground, and soon after dark the British retirement was proceeding smoothly. Chaytor began by clearing the troops on his right flank. The New Zealanders came down in the darkness from the slopes of Hill 3039-a very ticklish movement, carried out with the skill and perfect cooperation which always marked the brigade-and withdrew across the Wadi Amman. At the same time Mills led in his battalion from the extreme flank. The infantry then retired to the line from which they had moved to the assault on the night before, and the New Zealanders and Ryrie's brigade advanced a line of posts covering Amman, while the infantry and the Camels marched across the plateau to the west. By this time the morning of the 31st was well advanced, the removal of the wounded men of the New Zealanders and the Camels on the flank having occupied many hours.

The wet and cold and the marching on the sodden countryside had imposed great hardship upon all troops engaged at Amman; but the sufferings of the wounded were extreme. During the operations a number of motor-ambulances plied between the Jordan valley and Es Salt, but they were unable to traverse the soft road between Es Salt and Amman. Every seriously wounded man had therefore to be carried from Amman to Es Salt on the camel cacolets. It would be scarcely possible to devise a more acute torture for a man with mutilated limbs than this hideous form of ambulance-transport.

Even when the camels travel at a snail's pace on level ground, the wounded are horribly jolted; on country with steep gradients made slippery by rain, where the camels, fearful of falling, move irregularly, constantly sprawl, and often collapse, the agony inflicted is indescribable. "I had a rough spin," said a light horseman who, with a shattered arm, travelled by cacolet from Amman to Es Salt, “but when it seemed unbearable I reminded myself that the chap on the other stretcher on my camel had a badly broken jaw." Mills on the flank had not even sufficient camels for his wounded, and eleven men had to be tied on to horses. Beds of greatcoats, freely offered, were built up on each horse, and the wounded were placed face down with their heads to the horses' tails. Their hands were then tied under the flanks, and their feet secured in nose-bags at the front. In this fashion they were borne for twelve miles.

All through the engagement the three battalions of the Camel Brigade had fought with their usual recklessness. Their losses were sharp. Captain P. Newsam, Lieutenants Denman and Smith (2nd Battalion), Lieutenants G. E. Sanderson, O V. E. Adolph, and C. F. Thorby (4th Battalion), and forty men of other ranks were killed or mortally wounded; and Lieutenant-Colonel G. F. Langley (1st Battalion), Major J. Day, Captain J. W. Hornby, and Lieutenant Walbank (2nd Battalion), Major L. C. Kessels:' Captain A. J. Watt, Lieutenants J. C. Smith, and A. G. R. Crawford (4th Battalion), and 280 men of other ranks were wounded.

By noon the whole force, with the exception of the mounted rear-guards, was on the march. The 2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade moved by the road to Es Salt, while the infantry and the Camel Brigade, followed and guarded by the New Zealanders, used the track from Ain es Sir to Shunet Nimrin, by which the New Zealanders had gone up. Early in the afternoon small bodies of Turks approached the light horse rear-guards, but were held off without trouble. As the New Zealanders rode slowly through Ain es Sir in the night, they were followed by about 500 Turks. The Circassians of the Ain es Sir village, who had during the fighting been sulky and aloof, were fully alive to the British failure; picking up courage, they joined with a few Turks in the village and opened fire at close range upon the Wellingtons, and about a dozen of Meldrum's men were hit by the first volley. The revenge of the New Zealanders was instant and decisive. The night was wild and dark, with sleet and wind which chilled the men to their bones. Wet, sleepless, and almost worn-out with their prolonged fighting, depressed with the sense of failure and saddened by the thought of dead comrades, they were in no temper to reward treachery with mercy. As their friends fell from the saddles, they rushed the Circassian houses, drove the civilian riflemen out, and in a few minutes had killed thirty six of them. The retreat was not again molested. After a sorry night in the cold, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade at I a.m. on April 1st reached a camping-ground amid a nest of little vineyards surrounded by stone walls in the hills two miles east of Es Salt; a few hours later they continued the march through the town and down the main road to Shunet Nimrin. As each day of the Amman fighting went by, the position at Es Salt had become increasingly disquieting. Although often attacked, the 1st and 2nd Regiments of Cox's brigade had succeeded in blocking the thrust of the Turks down the Jordan valley from the north. But the enemy, steadily drawing reinforcements across the Jordan at Jisr ed Damieh from the direction of Nablus, had pressed in on Es Salt from the west and north. Shea had only two battalions of the 179th Brigade and Bell's light horse regiment to resist this encroachment, and to prevent a march against the rear of Chaytor's force at Amman. On March 2Sth the Londoners covered the position from the north and north-east, while Bell was in touch with the enemy on the north-west. That day 1,000 Turkish infantry with two guns marched towards Es Salt from Damieh, and 500 more were operating against Cox's two regiments on the plain. A rise of nine feet in the Jordan had thrown two or' the four bridges out of action and delayed all transport, and a great supply dump at Shunet Nimrin was disorganised by a raid of thirteen German airmen, whose bombs killed two British artillery officers and caused heavy losses among the Camels.

On the 29th the pressure at Es Salt increased, and on the 30th some 2,000 Turks were concentrated about the commanding hill-feature, Kefr Hudr, to the north. A captured Turkish officer informed the General Officer Commanding 179th Brigade that the enemy intended to attack on the night of the 30th. Bell was then ordered to take up a position on the left of the infantry, from which he could harass the enemy's flank if the assault were made. The information proved unsound, but the precautions led to a daring and successful little exploit by the light horsemen. Moving at 1.30 on the morning of the 31st, Bell led his men for two and a half miles along the track leading to Arseniyet and, dismounting, advanced on foot over rough country to high ground close to the enemy's right. After daylight the Australians crept to within 800 yards of an enemy machinegun post covering the Turkish flank. One troop under Lieutenant C. A. BennettoZ8crawled forward to within about 100 yards of the machine-guns without being observed, and fire from three Hotchkiss guns was opened on the post by the main body. Bennetto's men then rushed the position, supported by a second troop under Lieutenant H. E. McDonald. The Turks, surprised and demoralised, had no time to open fire before the Australians were upon them. The officer in charge and thirteen other ranks were killed, six were made prisoner, and three; machine-guns captured. Prosecuting his success, Bell ordered his squadrons forward along the rear of the Turkish infantrymen, who, caught by Hotchkiss fire, left their positions and fled into the shelter of the ravines. Many Turks were shot down as they ran, and several hundreds, including 300 cavalry on the Damieh track, were driven back in confusion over a distance of four miles. Bell sent an urgent message to the British infantry commander suggesting a general advance; but the position was deemed too obscure, and the force available too weak, for a definite offensive. The light horse casualties were three men slightly wounded.

Bell, a sound soldier of wide vision, did not at that time share in the nervousness of the High Command as to the Es Salt position, and always maintained that the hurried evacuation of the town on April 1st was a serious mistake in tactics. Discussion of the point is purposeless. Evacuation was ordered and carried out hurriedly, and not without some appearance of a break in the British morale. Defeat and dejection were stamped on the procession of fighting men, with all their strange train of paraphernalia, which that day thronged the mountain road between Es Salt and Shunet Nimrin. The sense of failure was also sharply accentuated by the unhappy multitude of terrified Armenians and other Christian peoples who fled from Es Salt down the track with the horsemen and infantry. The rejoicing which had followed the British occupation of the town had been succeeded, as the indecisive days of Amman dragged on, by uneasiness, then by fear, and, when the British withdrawal became known, by panic. The Moslems of the town had watched with sullen disapproval the happy demonstrations of the Christians; and now that the Turks had prevailed, all those who had rejoiced and had shown sympathy with the Londoners and the light horsemen feared for their property, their women, and their lives. Up till then they had during the war been spared outrage. Now they feared that the blow would fall, and on the night of the 31st a great many Christians packed up all that they could carry to the Jordan, and prepared for flight. Before dawn the leaders of this tragic, motley throng of aged men and women, of parents and families-even to babies in arms-of rich and poor, rough and gentle, were far down the road. Some had camels and donkeys of burden, some drove their sheep, but most walked heavily laden. The night was wet and cold; the following day was marked by heavy showers; the road was steep and narrow, flooded and rough.

*They pressed on, at first strong and confident in the thought of the British troops behind, afterwards exhausted and sore footed, and with their terror increasing as battalion after battalion, regiment after regiment, marching swiftly past, left them, as they believed, to the mercy of their fanatical enemies. The light horsemen, moved by their plight, lifted women and children up and placed them in front of their saddles; not a few dismounted, worn as they were, and allowed the wretched fugitives to ride their horses. At every bend in the steep mountain track stood insolent and truculent Arabs, taking a devilish delight in the strange and tragic procession, and firing their rifles into the air-a favourite pastime with these natives when moved by deep excitement. Still more distressing was the condition of the British wounded. A large advanced dressing-station had been established at Es Salt, and when the nervous speed at which the evacuation was undertaken overtaxed the capacity of the motor-ambulances, a large number of victims of the fighting had to make the journey down the mountain-side in the ghastly camel cacolets. The road was very greasy, and on the steep gradients the camels frequently fell. The morning was made hideous with the groans of the wounded.

By the afternoon of April 2nd the whole force had gained the Jordan valley. Leaving the 180th Infantry Brigade to hold a bridgehead at Ghoraniye, Shea withdrew his men, less the 1st Australian Light Horse Brigade, to the west side of the Jordan. Despite the complications caused by the floods, the hastily-thrown bridges had proved equal to the enormous traffic during the week's operations. The magnitude of the transport required for the supply of a few brigades of men engaged a long distance from the railway, was shown by the fact that no less than 30,000 animals recrossed the bridges during the withdrawal.

Defeat is rarely admitted during the progress of a campaign. The British War Office proclaimed to the world that the Amman raid was successful, and emphasis was laid on the destruction of the few miles of railway on the level country south of the position. But General Shea made no attempt to disguise his failure. “The objects of the raid on the Hejaz railway," he said, in his report written a fortnight later, " were the destruction of the tunnel and viaduct, of Amman station itself, and of the railway for some distance north and south of that place. Adverse weather conditions and the opposition encountered prevented these objects from being completely attained." The simple truth was that, with the tunnel and viaduct still sound, the damage done to the line was trifling and of very little embarrassment to the enemy. The failure was expensive. The casualties were;

| Unit | Casualty | Officers | Other Ranks |

| Anzac Mounted Division (including the Camel Brigade) | Killed | 11 | 107 |

| Wounded | 40 | 511 |

| Missing | 2 | 53 |

| AIF | Total | 53 | 671 |

| British Infantry | Killed | 4 | 55 |

| Wounded | 23 | 324 |

| Missing | 2 | 68 |