Topic: AIF - DMC - Scouts

The Australian Light Horse,

Light Horse Duties in the Field, Part 4

A Criticism of the Article

The following essay called Light Horse Duties in the Field was written in 1912 by Major P. H. Priestley, who at that time was on the C.M.F. Unattached List. The article appeared in the Military Journal, March 1912.

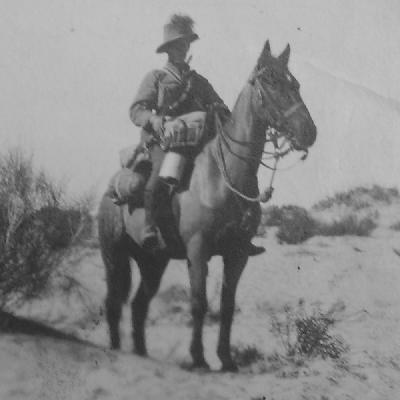

Prior to that Priestley served in South Africa 1901-2 with the 5th South Australian Imperial Bushmen in Cape Colony and Orange River Colony and was awarded the Queen's South African Medal with four clasps. During the inter war years he served with the South Australian Mounted Rifles 1900 - 1910 when he was placed on the unattached list. At the outbreak of the Great War, he enlisted with the 3rd Light Horse Regiment and embarked with "A" Squadron. He was Killed in Action on 3 May 1918.

The following is a 3 part series of this article. A fourth part was attached as his article was critiqued by Major F. A. Dove, D.S.O., A. and I. Staff, in the Military Journal, May 1912. Both articles give valuable insights in the basic thinking around the use of Light Horse scouts, detailing both theoretical ideas peppered with experience wrung from the recent war in South Africa.Dove, FA, Light Horse Duties in the Field - A Criticism of the Article, Military Journal, May 1912, pp. 430 - 433.

Light Horse Duties in the Field - A Criticism of the Article

Scouting.

In dealing with the above subject, Major Priestley gives first place, rightly, I think, to the subject of scouting. There are already alleged authorities who assert that the rise of the aeroplane has reduced the importance of scouting. Such ideas, if allowed credence, will most seriously affect the efficiency of our Light Horse. Strategical reconnaissance perhaps will soon depend more on the aerial fleet than on the cavalry corps. But as every unit in the field is responsible for its own protection against surprise, it would take an enormous number of aeroplanes to provide every division, brigade, and regiment with flying scouts. Besides, the anti-airship armament will effectually prevent those low, near-the-earth flights which alone would give satisfactory results in tactical reconnaissance anywhere except on an open plain.

Scouting is certainly the first duty of Light Horse in the field, but is often taught last, or not at all.

As it is a pet subject of mine, I welcome Major Priestley's article, and, while agreeing with the great bulk of it, must join issue with him on certain of his conclusions which are not in accordance with the lessons of my experience and study.

The following remarks are merely submitted with a view to arouse interest in a very important branch of Military Training.

Throughout the article (which deals with protective scouting only), the author insists that the scouts must never be out of sight of their troop-leader. In my opinion, scouts who cannot be trusted out of sight of their leader are not scouts at all, but mere useless appendages to the troop, pushed out as a matter of form. It follows, if they arc' to remain in view of the troop that in almost every case the enemy sees scouts and troop at the one time.

Major Priestley contemplates (apparently) using single scouts only for screening work. I found this in practice weak and wasteful of men. Two scouts acting in co-operation did better work than four acting independently. It was found in South Africa better for all purposes to send out scouts in small groups (patrols) of two, three, or four men. As long as the troop-leader can see one of the group, or a connecting file between him and them, he is "in touch" with his scouts, and the latter are not tied down to limited frontages or definite lines of advance. Scouts more than any other soldiers must have free play for initiative. If many restrictions are placed upon them, they will be constantly occupied in considering what they ought not to do instead of what is best to he done.

The necessity of working scouts in groups rather than singly is the greater in proportion as the men are less trained. In protective scouting practically every trooper has to take his turn, so that high individual efficiency in scouting is not to he expected, even in the very best squadrons. Men who are specially adapted for the work and who have studied and practised assiduously sometimes prefer to go out alone, but such men are not employed in the business we are discussing.

The author treats of the capture of his scouts (in full view of the troop leader, of course) in a matter-of-fact sort of way. Now, it is not permissible for a scout to be captured without his making a clash for liberty and a fight if cornered.

I have frequently seen determined scouts get away scatheless after riding up to almost the muzzles of the Boer rifles. Though the business of the scouts is not to fight little battles on their own, it would be a fatal mistake to let the enemy know that they have no sting. On the contrary, war is “a game for keeps," as the schoolboys say, and our scouts should be essentially combative and aggressive in dealing with the enemy's scouts and patrols in order to establish a moral superiority as soon as possible. In the early part of the war in South Africa the British scouts appeared paralysed, and really were demoralized on account of the frequency with which they were cut tip by the Boers. It will be better for us to constantly instruct our Light Horse that they should never let a chance pass of killing, capturing, or frightening the enemy's scouts, unless some very important purpose is served by permitting them to escape. Once our scouts have demoralized those of the enemy we have taken the best of all steps to protect our own farm and to facilitate the acquisition of information about the enemy.

It must be clearly understood that I am dealing only with the ordinary routine scouting in connexion with advanced, flank, or rear guards or the protection of any formed body of troops when moving.

The scouting solely for information will, I take it, is undertaken by selected and specially trained men whose work is carried on wholly or mostly far away from support, and is of a secret, stealthy nature, concealment from the enemy being almost essential to success. The writer's suggestion (page 179) for dealing with a hill difficult of ascent rather beyond the scope of a flank troop of the vanguard, and yet within long range rifle fire of the column, does not appear to me to be sound. In fact, it would cheerfully be the means of cashiering the troop-leader who would pass such a feature unsearched.

The troop-leader must take a large view of the country within his sphere of operations. Such a feature as mentioned would be observed from afar and duly considered; the troop-leader would know whether his scouts should or should not venture so wide, and if not, he would send a non-com and two or more men as a patrol to search the dangerous ground, climb to the; top if found unoccupied, and stay there until the near approach of the flank guard assured its safety.

I am not quite clear as to how Major Priestley proposes to form his screen, but the impression is of a number of troops moving abreast each with its own frontage to watch and providing for its own safety.

Personally I would have the screen composed as a rule of small patrols furnished by one or two whole troops, maintaining touch and direction from a common centre, and the remainder of the squadron in support. With a little training and practice the squadron leader can manoeuvre his whole command in a flexible formation and be in “touch" with every part, though many of his men will be constantly out of view. I have seen the type of squadron leader and even regimental commander who could not bear to have any of his men out of his own sight. Whenever a patrol was hidden by an intervening feature, he got on “pins and needles" and generally sent off another patrol to look for the first. Such a man lacks the equanimity essential in one who aspires to be a successful leader.

Coming now to part 3 of the article, dealing with the flank guard, here again I am not sure as to the methods he favours, but apparently (vide pages 181, 182) he proposes, to establish a complete chain of men 50 yards or so apart, some singly, some in troops, from the outer edge of the advanced guard to the corresponding portion of the rear guard. I do not know where he is going to get sufficient men for such a formation, which, even if completed, is absolutely weak in defensive power and fearfully wasteful of numbers. The plan was tried by both regular cavalry and yeomanry in South Africa in easy country (being clear and undulating), but always with bad results. The flank guard finally resolved itself into a procession of single troopers or groups sternly intent on following exactly behind the unit next in front and at the prescribed number of paces; scouting was out of the question, and fighting the real business of a flank guard was impossible. Further, if one man lost connexion with the scout he was following, all the hundreds coming behind might be led in a false direction. With anything more than a single regiment on the march such a system, requires too many men to be effective. A mixed brigade with guards out to front and rear would cover a length of at least 6 miles from the advanced to the rear patrols in average country. With a screen 6 miles wide in front and a similar one to the rear there would be a perimeter of 24 miles. It is easy to calculate the number of single scouts required in this case at 100 yards intervals or distance as the case may be-say 400, add the necessary supports and then the main guards, and you basically run to 2,000 men - too many to detach from a force of 4;000 to 5,000 all told.

The work of a flank guard can ordinarily be done best by the seizing and holding with just a sufficient force of a succession of defensible points on the flanks of the column. The O.C. flank guard requires to study the map before he marches out, and then both the map and the ground as his troops move along. He is only concerned with the protection of the main body; he has no direct concern with the advanced or the rear guard, and he need not keep touch with them, though if he can do so by use of signalling all the better. As all the detachments are (or should be) in constant communication with the main body, the O.C. flank guard will be informed of such happenings to front or rear that necessitate action or preparation on his part.

I hope the second paragraph on page 185 is not meant to imply that our protective troops should be content to merely watch hostile scouts who ride along parallel to and observing us. If so, it is not war. These prying gentlemen should be sent off with a “flea in their ear" in double time. I would again repeat that protective scouts should be aggressive, and not hesitate to tackle scouts or patrols not superior in numbers that attempt to bar their way or whom they can surprise. When there is time the senior scout of the patrol should inform the troop-leader of the situation before opening fire; but no hostile scout should be allowed to escape because the officer is not present to order the men to shoot. It is a mistake to think that protective troops are only intended to act defensively. The best defence always is attack.

F. S. Regulations, page 101, say

"Tactical reconnaissance is one of the most important duties of the protective cavalry, who when touch with the enemy is gained will assume a vigorous offensive, drive in the enemy's advanced troops and discover his dispositions and intentions."

Previous: Part 3, Scouts, Pointers, and Connecting Files of the Flank Guard

Next: Brigade Scouts

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Light Horse Duties in the Field, Part 4, A Criticism of the Article