Topic: BatzG - Anzac

The Battle of Anzac Cove

Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

Bean's Account, Part 1

The following is an extract from Bean, CEW, The Story of Anzac: the first phase, (11th edition, 1941), pp. 245 - 280.

CHAPTER XII

THE LANDING AT GABA TEPE

By 8 pm on Saturday, April 24th, the four transports of the 3rd Brigade were close under the island of Imbros. Night had fallen an hour before. All the afternoon they had been sailing through a perfect sea. As they neared Imbros the first preparations were made on board. Thus in the Devanha, carrying a company and the headquarters of the 12th Battalion, the men had a meal at 5 o’clock, and immediately afterwards, before dark, everyone was brought on deck and put in his proper place. As the transports moved easily through the evening sea and neared the rugged slopes of Im bros, the junior officers inspected their platoons. Their duty was to see that each man had two empty sandbags rolled round his entrenching tool; that the pouches of his equipment were filled with 200 rounds of ammunition; that the heavy packs, crammed with the soldier’s simple wardrobe, were fastened over the shoulders with two loops in such a way that they could be thrown off immediately if a boat were sunk; that the magazines of rifles were empty - no shots were to be fired before daylight; that water bottles were filled; and that each man carried, tied behind him, the two little white bags which contained two extra days’ rations (a tin of bully beef, a small tin of tea and sugar, and a number of very hard coarse biscuits in each bag). They had tried to stain these white bags by boiling them in tea, coffee, and cocoa, but though the tea was black, the bags came out nearly white. As each man was inspected, he was ordered to put his kit down where he could find it in the dark.

By 6 p.m. the inspection was over. The men were told that they could rest till eleven, and the old Colonel (Clarke) suggested to his officers: “You fellows had better go and have a sleep.”

The Colonel himself lay down in a cabin put at his disposal by the ship’s captain. Presently Lieutenant Margetts, a young master of the Hutchins School, Hobart, crept in to see if the “old man” needed any service. The cabin was dark, and he thought his chief was sleeping. But, as he looked in, the Colonel said: “Margetts, are the men all right?”

Margetts climbed on deck and walked round among the dark forms. The transports were now anchored off Kephalos harbour, at the eastern end of Imbros. At 11 p.m. the order was given to get the troops into the destroyers, which crept up on either side of their respective transports.

The two companies of the 9th Battalion in the Malda clambered into the Beagle and Colne; the two of the 10th from the Ionian into the Scourge and Foxhound; the two of the 11th from the Suffolk into the Chelmer and Usk. As the Devanha carried only one company of the 12th and some medical officers, stretcher-bearers and others of the 3rd Field Ambulance, only one destroyer. the Ribble, came alongside her. The night was so still that the Devanha’s captain ordered: “Lower gangway.” Down this the troops filed on to the destroyer’s deck in half the time that had been required with the rope ladders on which they had practised for nearly two months. Five minutes before midnight the Ribble, with her decks crowded, and towing behind her the Devanha’s empty rowing-boats, left the transport. The dark shape of the ship faded slowly behind. The destroyer came up with the six others, all similarly loaded, motionless on the water.

Not a glimmer showed on deck: only the moonlight shone faintly through the clouds on the crowded men and on the silken sea. Lieutenant-Commander Wilkinson of the Ribble leant over the bridge and said to the men below: “You fellows can smoke and talk quietly. But I expect all lights to be put out and absolute silence to be kept when I give the order.” In the interior of the destroyer, on the mess-deck, where the men who were to land in the second tow were waiting, two old sailors were carrying cocoa to the troops. Down in the tiny wardroom, where shone a solitary light, Colonel Clarke, who commanded the 12th. Lieutenant-Colonel Hawley, his second- in-command, Major Elliott, Lieutenant Margetts, and the adjutant sat over a cup of cocoa.

The seven destroyers had begun to move slowly, barely making headway. After two or three miles they stopped again, waiting for the moon to sink. Unseen, but not far ahead of them, were the three battleships carrying the first half of the 9th, 10th, and 11th Battalions, which would be first landed. These men, sleeping on the battleships’ mess-decks, from which the crews had turned out in order to give them the chance of a rest, were called at midnight. A cup of hot cocoa provided by the ship was given to them. At 1 a.m. the ships were stopped on the sea between Imbros and the Peninsula. The moon was still high, and the shape of land was at times visible to the east. The hulls of the battleships lying near one another on the water, motionless, were difficult to pick out except through glasses. They had all swung out their boats, and those of the three “covering” ships, which carried no troops, the Triumph, Majestic, and Bacchante, were sent alongside the Queen, Prince of Wales, and London, which were the troop-carriers. Twelve rowing-boats were brought alongside each of these three vessels. These were made up into four tows of three boats, each three being towed by one of the warships’ small steamboats. Thus two tows lay on either side of each transporting battleship, and into these the troops climbed quietly down rope ladders. The only sound was the shuffle of the men’s heavy equipment or the occasional grounding of a rifle butt. Many a naval officer noticed how silent and orderly, now that it had come to business, were these troops whose name had terrified Cairo. By 2.35 a.m. the rowing-boats were full, and dropped back in long strings behind the battleships. At 2.53, the moon being now very low, the ships moved slowly ahead, towing the boats behind them. Some of the destroyers, closing a few minutes later, passed the shapes of big ships with strings of boats behind. At 3 o’clock the moon sank and the night became intensely dark.

At 3.30 the battleships stopped, and the order was given to the tows to go ahead and land. The small steamboats behind the battleships cast off, each with its tow of three ships’ boats behind. As the hawsers took the strain, the boats began to leap and race. The tows were to form all twelve in line and then make for the beach: the direction was to be given by the naval officer in charge of the starboard or southernmost tow; the other tows were to keep abreast of him, with about 150 yards’ interval between each one and the next.

There was some difficulty in getting into line. The night was so black that it was often impossible to see the next tow on either side, much more the whole line of them. Some of the tows appear to have sandwiched themselves into a wrong place in the line. But there could be no waiting or indecision. The battleships were coming on slowly behind. The small steamboats raced due east, the rowing-boats behind them. In each boat were from thirty to forty soldiers, four seamen, and a coxswain. In the steamboat ahead of each tow, which carried no troops, was a naval officer, with a senior officer to every four steamboats; in the last rowing-boat of each tow was a midshipman. The men, with their heavy packs and their kit hanging loosely on their shoulders, were crowded in the boats, the seamen among them ready to cast loose the tow rope and get out the oars. The senior company officers in some cases sat beside the midshipman at the tiller of the last boat. There was no sound, save the swift plunge and wash of the boats and the throbbing of the small engines. Suddenly, on the horizon ahead of the boats, a faint hazy band of white light shot into the sky, moved restlessly for half a minute, and vanished. It was a searchlight. For one instant the hearts of the few officers who noticed it flew to their throats. Could it be on Gaba Tepe? The anxiety passed. Low on the horizon in front of the light there showed a dark irregular shape which could only be a line of intervening land. The searchlight was in the straits beyond the Peninsula. A second ray shot out lower down the straits, flickered for a moment, and faded.

Half an hour after the ships had been left, the first faint signs of dawn began to show ahead of the boats.

About that moment orders were received by the seven destroyers, waiting in the dark behind the battleships, to follow the tows towards the land. In the Ribble Commander Wilkinson leaned over the bridge and said: “Lights out, men, and stop talking. We’re going in now.” The speed increased; the destroyer began to throb. Immediately afterwards she passed close by the dark shape of a large warship. The men in the Ribble could see all seven destroyers, now in line, moving swiftly in.

In the twelve small tows ahead it was still too dark to make out any but the nearest abreast. Under the sky could be seen, definitely for the first time since the set of the moon, the dark shape of land. Every brain in the boats was throbbing with the intense anxiety of the moment: “Will the landing be a surprise, or have we been seen?” As the dull line of the land rose higher and higher above the nose of the boats, the suspense was almost unbearable. The panting of each steamboat seemed to those behind it a noise to rouse the dead. Surely, if there were men on the shore, they must presently hear it! Yet the land gave no sign of life.

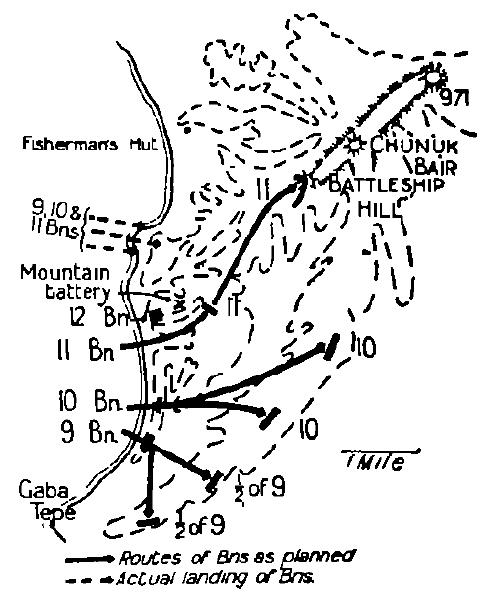

The naval officer in charge of the right-hand tow was to have given the direction, but it was too dark to see at times even the string of boats next abeam. His own seems to have gone straight enough, but the second or third to the north of it took a course diverging gradually to the left. Commander Dix, who was in charge of the flotilla, was in the northernmost, with part of the 11th Battalion. Several times after leaving the London he appeared to find the steam- boat on his right too close, for he called out to keep more to starboard. The naval officer in the southernmost found that the whole line, except the tow next to him, was heading for a different part of the shore. The course he was taking would land himself and his next neighbour isolated on the beach north of Gaba Tepe. Accordingly he swung his steam- boat to the left, which would bring it across the bows of the others. The naval men appeared to see far better in the dark than did the troops, for, as the land drew closer, one after another picked up this movement, swung several hundred yards northward, and then straightened again.

There was still no sign of any sort from the shore. The water was as smooth as satin - a gloriously cool, peaceful night. In one of the central tows, carrying the 10th Battalion, the steamboat had already cast off the rowing-boats. Only the soft dip of the muffled oars in the water broke the silence. They were forty or fifty yards from the shore. “There’s no sound,” whispered Colonel Weir to the officer beside him.

The eleven other tows must have been very close, hut they could not be seen by one another. The northernmost had swung to the left and then back again, nearly colliding.

About this moment from the funnel of one of the northern most steamboats there flared out a trail of flame. Special instructions had been given to the crews to prevent this occurrence, but it is not easily avoided. Three full feet of sparks and flame continued to trail for twenty or thirty seconds. A high plateau of land was above the boats at this moment, with a round jutting knoll, 200 feet high, at the foot of it. It was Ari Burnu point.

The voice of Commander Dix broke the silence. “Tell the colonel.” he shouted, “that the dam’ fools have taken us a mile too far north.”

Just then - at 4.29 a.m. - on the summit of another and rather lower knoll a thousand yards south there flashed a bright yellow light. It was seen by almost everyone in the boats: some took it for a signal lamp; others for a bright flare of shavings or a small bonfire. It glowed for half a minute and then went out.

There was deathlike silence for a moment. Then suddenly: “Look at that!” said Captain Leane in one of the northernmost boats. The figure of a man was on the skyline of the plateau above them. A voice called on the land. From the top of Ari Burnu a rifle flashed. A bullet whizzed overhead and plunged into the sea. A second or two of silence …. four or five shots as if from a sentry group. Another pause-then a scattered, irregular fire growing very fast. They were discovered. After the tension of the last half-hour the discovery brought a blessed relief.

At this moment the twelve tows were very close together, running in to the foot of the Ari Burnu knoll. The knoll juts out in a small cape, and the boats of the 9th and 10th Battalions, striking the point of this, were the first to reach the land. The 11th Battalion ran past the north of it a little further before arriving at the beach. The naval steamboats had now cast off all the tows. Each steamboat carried a machine-gun in her bows, not to be used except by order of the senior officer of the troops in the tow. The picket-boat, with Major Salisbury’s tow of the 9th Battalion, immediately backed out and began to fire, her small gun pointing up towards the flashes on the edge of the plateau above. The rowing-boats with the troops were paddling the last short space to the land. The smaller life-boats and cutters ran in till the water shoaled to two or three feet. The larger “launches” and “pinnaces” grounded in deeper water, whereupon the men tumbled over the bows or the sides, often falling on the slippery stones, so that it was hard to say who was hit and who was not. Most were up to their thighs in water; some, who dropped off near the stern of the larger boats, were immersed to their chests. Others, barely noticed in the rush, slipped into water too deep for them. The heavy kit which a man carried would sink him like a stone. Some were grabbed by a comrade who happened to observe them; one was hung up by his kit on a rowlock until someone noticed him; a few were almost certainly drowned.

It was at 4.30 a.m. on Sunday, April 25th, half an hour before the opening of the British bombardment of Cape Helles, that the Australians landed at Ari Burnu. The first bullets were striking sparks out of the shingle as the first boatloads reached the shore. Three boats near the point had become so locked that only those on the outside could use their oars. One of these, containing men of the 9th Battalion and Captain Graham Butler, their medical officer, and a boat of the 10th Battalion, with Lieutenant Talbot Smith and the scouts of the battalion, were among the first on the point. In many cases the men had been told that they would have to run across ten or fifteen yards of sand, line a low cliff four or five feet high, drop their packs and form up, and then rush across 200 yards of open to the first hill. They raced across the sand, the bullets striking sparks at their feet, and flung themselves down, as instructed, in the shelter of the sandy bank - which in some places amounted to a low cliff - where the hillside ended and the beach began.

The fire was increasing fast. A machine-gun was barking from some fold in the dark steeps north of the knoll; another was on the knoll itself or on the edge of the plateau above and behind it. The seaman who, as if he had been landing a pleasure party, was handing Captain Butler his satchel out of the boat, fell back shot through the head. In the tows of the 11th Battalion, which were to the north of the point and had still 200 yards of water to cross before they touched the beach, bullet after bullet was splintering the boats or thudding into their crowded freight. Every now and then a man slid to the bottom of the boat with a sharp moan or low gurgling cry. The troops and the seamen crouched as close and as low as they could, with their backs hunched. Occasionally some heavier missile, as from a small Hotchkiss gun, splashed heavily into the surface of the sea. In one boat an oar was splintered, and a corporal tried to sound the depth with it. The water, by its colour, was shoaling fast. A “tag” was current in the 11th Battalion, based on the statement of a sergeant, that bullets made a noise like small birds passing overhead. At this crisis Private “Combo” Smith, of the 11th Battalion, set one whole boat laughing by looking at the sky and remarking to “Snowy” Howe: “Just like little birds, ain’t they, Snow?” The last rowing-boat in each tow had been placed in charge of a midshipman. To the naval folk these youngsters were officers, but to the Australian soldier they were children. Amidst all this heavy firing, when boatload after boatload moved in huddled and helpless, unable to reply, officers and men saw these boys sitting, sometimes standing. high in the stem beside the tiller. In more than one case the Australian officer in the boat bore the brave figure of that child in his mind to help him in the wild hours which followed. The midshipman beside Major Drake Brockman, of the 11th Battalion, in the second tow from the left, was a small red-headed slip of a boy. As the boat's nose grated on the shore, he pulled out a heavy revolver and clambered over the backs of the men, waving the pistol and shouting in his young treble: "Come on, my lads! Come on, my lads!" After running across the beach he mournfully pulled himself up, as he realised that his duty was to go back with his launch.

The boats of the 11th Battalion hit the shore 200 or 300 yards north of the point of Ari Burnu. Those of the 9th struck the point itself or its southern shoulder, and some of the 10th landed just south of it. From every boat the men doubled across the sand and took breath under the bank, whither also the wounded from the boats were hauled. Many were fixing their bayonets as they ran across the shingle. In other cases the officers or sergeants, as they and their men lay under the bank, gave the orders to strip packs - load the magazines with five or ten rounds - close the cut-off - pull back safety catches. No shots were to be fired till daylight

[From: Bean, p. 255.]

The men were ashore and mostly alive, but the place was clearly the wrong one. Anyone who depended upon a set plan for the next move was completely bewildered. It had been hoped that the halt under the sandy bank would be long enough to allow all the companies to land, form, and carry out an organised attack across the open against the first ridge.

But there was no open. Some officers thought that the knoll of Ari Burnu was Gaba Tepe itself. A high rugged slope pressed down on to the beach. A fierce rifle-fire swept over the men. They had been landed in the dark on an utterly different coast, and were lying in little parties of boatloads and platoons out of sight of most of their comrades, their clothes heavy with water, and their rifles choked with sand. In consequence of the swing of the southernmost tows, those who should have formed the right of the 9th were mixed up with the right of the 10th. Above some of the 9th, immediately south of the point, the bank was so high and steep that those who tried to clamber up it slipped back.

Something was clearly wrong. Everything seemed wrong. The 9th and 10th, on the point itself and on its southern bend were fairly protected from rifle-fire. Many of the Turks were shooting at the destroyers further out; but north of the point where the 11th landed, a machine-gun in the foothills 500 yards to their left was shooting into the men behind the bank, and the grassy tussocks on the sand slope above it gave no better protection. As Lieutenant-Colonel Johnston and Corporal Louch lay there side by side, a bullet thudded into the sand between them. The country was unrecognisable. They had not the least idea as to whether the other tows had yet landed.

“What are we to do next, sir?” somebody asked of a senior officer. “I don’t know, I’m sure,” was the reply. “Everything is in a terrible muddle.”

But every authority, from Sir Ian Hamilton and General Birdwood down, had dinned into the troops: “You must go forward - you are the covering force. You must get on, whatever the opposition.” There was a proportion of men and officers who barely waited to throw off their packs. Captain Leane and the men with him did not even charge their magazines. There was no time for that. They dropped their packs, and went straight into the scrub and up the steepening slopes. On the tip of Ari Burnu Point Lieutenant Talbot Smith with the scouts of the 10th Battalion, thirty-two in number, had struck the shore just after the first shot was fired. “Come on, boys,” he cried, “they can’t hit you!” He had told them to leave their packs in the boat.

Smith had lectured his small flock in one of the gun casemates of the Prince of Wales at 10 o’clock the night before drawing sketches for them on the breech of the 6-in. gun. Their task was to hurry on and catch the Turkish battery near the objective ridge, and he had requested one of the ship’s gunners to show them how to damage a gun by burring the screw in the breech. He now ran across the beach, climbed a short way up the slope, and turned: “10th Battalion scouts,” he shouted, “are you ready?” He then led them straight up the height, while the Turks above were firing over their heads. From the left-hand edge of the plateau above could be seen the flash of a machine-gun. They made up the hill towards it. There was no opportunity for subtle co-ordination such as had been planned. The scouts or the more adventurous spirits started first. A certain proportion of the 9th and 10th, who were dropping their packs under the bank on the southern bend of the point, clambered uphill on the word being given by Colonel Weir. Others saw the forms of these men moving in the dark, and set off with them. The result was that a few minutes after the landing, a rough line about six companies strong began the difficult ascent. Any idea of keeping touch or formation during this climb was out of the question. At the very start, on the southern bend of the point where Major J. C. Robertson and part of the 9th landed, they were faced by a steep bank as high as the wall of a room. They endeavoured to climb it, but slipped back. Then someone found a rough foot-track leading round it, and up this they clambered on to the scrubby knoll. The scrub was mostly composed of small stout bushes of prickly oak, waist high, leaved like a diminutive holly, or else of a taller “arbutus” with naked orange stems and leaves like those of a laurel. Later, when the light increased, every hillside in this part of the Peninsula had the appearance of being covered with gorse. The growth was stubborn, and, in the steep gravelly waterways with which the hillside was scored, it was as much as a strong man could do to fight his way through it, to say nothing of carrying his heavy kit and rifle. Men grasped the arbutus roots and hauled themselves up by them, sometimes digging their bayonets into the ground and pushing themselves up to a foothold. As they climbed higher towards the plateau, the sides became steeper, until they were nearly precipitous. The men of the Navy, watching the troops flinging themselves like cats up the hillside, carried back the story of it glowing to the ships.

Ari Burnu Knoll, jutting from the foot of the plateau, was less steep than the sides of the plateau itself. Within 1 minute or two the men were reaching the top, where a small square machine-gun post had been sunk, with beams as if to support a roof. From this post a trench ran back along the neck, connecting the knoll with the side of the plateau. The Turks had not erected any obstruction of barbed wire in front of this trench, or of any other met with by the Australians that day, and they were bolting from the top of the knoll before the Australians reached it. In the trench lay a wounded Turk. Captain Graham Butler, medical officer of the 9th Battalion, stopped to attend to him; the line was scrambling up the hill ahead.

Those of the 11th Battalion who were lying under the bank north of Ari Burnu, under a heavy fire from the left, were out of sight and touch with the men whom Colonel Weir and others had started on their rush. But presently they perceived the figures of men climbing up the knoll above the point. They took these to be the 9th and 10th Battalions, landed to the south of them, and they too started inland up the slopes north of the point, which led to the same plateau. The hill grew steeper. Far above on the skyline they could see the forms of Turks moving. The men had been constantly warned, on the authority of officers with experience of the Kurds and less disciplined Turkish troops, that the Turks mutilated men whom they captured or found wounded, and in these early days the Australians nursed a strong suspicion and hatred of the enemy. Whenever a Turk was “put up” during these early hours of the fight, he was chased with shouts of “Imshi-yalla, you bastard !” “Igri,” “Saida,” and other tags of “Arabic” which were now part of the Australian speech. Half-way up this first hill two Western Australians stumbled on a Turkish trench. A single Turk jumped up like a rabbit, threw away his rifle, and tried to escape. The nearest man could not fire, as his rifle was full of sand. He bayoneted the Turk through his haversack and captured him. “Prisoner here!” they shouted. “Shoot the bastard!” was all the notice they received from others passing up the hill. But, as in every battle he fought, the Australian soldier was more humane in his deeds than in his words. The Turk was sent down to the beach in charge of a wounded man.

On the southern bend of the point, after Weir’s line had started, a certain number of men who had lost touch with their officers were still crouching under the bank, loading their rifles and cleaning them of grit. Bullets from above were whipping in among them, and some of the men were lining the bank and shooting up at the flashes of the Turkish rifles on the skyline. Graham Butler, who had been attending to several wounded men on the beach, saw the futility of this, and the danger to those ahead. He urged these men not to wait to load, but to push on with their bayonets alone; and though he was an older man than most of his comrades, he led them at a swift pace up the hill.

The face of the height was so steep that those who were wounded rolled or slid down it, until caught and supported by some tuft of scrub. Here and there a man hung over a slope so precipitous that Butler, going to his help, had to cut steps in the gravel face with his entrenching tool in order to reach him.

The first men were now reaching the plateau. Talbot Smith and his scouts from the south of the point were climbing neck and neck with the swiftest men of the 11th from its northern side. Ari Burnu Knoll had been left behind and below them, and they had converged on to the sheer side of the plateau. Captains Leane and Annear, and Lieutenants Macdonald and Selby, of the 11th, were beside Talbot Smith and his scouts. Some hint of this line of grim men silently climbing to them in the dim light had reached the Turks, and they were beginning to bolt. The flash of the machine-gun on the top had ceased for some minutes, though a necklace of rifle flashes still fringed the lower crest to the right.

The first Australians clambered out on to the small plateau. A foot or two inwards from its rim was a Turkish trench, from which a few Turks seemed to be running back to the inland verge of the summit 200 yards away. From there a heavy fire still met the Australians appearing over the rim of the plateau, and was sufficient to force the first men to take what cover they could on the seaward edge. They refrained from jumping into the trench, there being a notion among all troops at the beginning of the war that the enemy would leave his trenches mined. But the earth from the Turkish trench had been heaped up, as usual, along its front (or seaward) side, making a parapet a foot high, over which the garrison of the trench could fire. Behind this imperfect cover the leading Australians flung themselves down, while the fire from the other side of the plateau and from the dimly-seen ridge beyond swept fiercely over them. Lieutenant Macdonald of the 9th,lying beside Captain Leane, was wounded in the shoulder. Captain Annear was hit through the head and lay there, the first Australian officer to be killed.

Within a few minutes, as other men reached the plateau, the Turkish fire from its farther side began to slacken. A little to the left of Leane two of the enemy jumped up from the trench and fired down at the approaching men. Batt -batman to Lieutenant Morgan of the 11th - fell wounded. But four or five men who were reaching the summit at that moment made for the Turks, who ran across the small plateau. One was nearly caught, when an Australian stepped from behind a bush and bayoneted him in the shoulder; the other was shot on the farther edge of the summit, where he rolled down a washaway in the steep side and hung, dead, in a crevice of the gravel. Three more Turks sprang up and made for Major Brockman as he reached the top. An Irishman, an old soldier of the Dragoon Guards, killed all three. Major J. C. Robertson, of the 9th, was wounded. The fatal Australian fire from below, which Graham Butler stopped, had been responsible for the loss of at least one brave man. On the very edge of the plateau Sergeant Fowles was grievously wounded by one of the bullets. “I told them,” he said as he lay there dying in the Turkish trench - ‘‘I told them again and again not to open their magazines.”

The plateau, which one small party after another was now reaching at the end of its breathless climb, was a small triangular top with all its sides very steep. From the Turkish trench on its face two communication trenches ran back some 200 yards to the far edge of the hilltop. Later in the day, when these trenches were occupied by New Zealanders and others in reserve, Colonel PIugge of the Auckland Battalion had his headquarters there. The hilltop was accordingly named “Plugge’s” (pronounced Pluggie’s) Plateau.

The troops who followed the bolting Turks across the plateau found themselves suddenly brought up on the verge of a deep valley which ran below them. To the north the valley side was sheer, but further south, where the slope became sufficiently gentle to give a foothold to odd tufts of scrub, a zigzag path led down into it. By the path were three tents, partly screened with dry brushwood. The Turks, scurrying back across the summit, knew this path and dropped down it, while the Australians were checked by the cliff. Below the path and the tents was the gorse-like scrub of the valley, which covered the opposite hills also. The forms of the fugitives could be dimly seen doubling down through the bushes and up a track upon the other side. Several of the men stood on the edge of the plateau firing at them. A constant rifle fire came from the enemy somewhere on the heights across the valley.

A few of the leading men dived straight down the gravel precipice in pursuit. Talbot Smith and his scouts stood for a few moments on the edge. Smith looking at his map. Then they plunged down the path by the three tents to their task of finding the Turkish guns. Lieutenant Fortescue of the 9th, who had lost sight of most of his men in the bushes on the way uphill, “skidded” down the landslide on the farther edge and missed all the rest, except two who happened to slide down the same gutter. But while these first parties were starting to follow the Turks inland, the men of the battleship tows of the 9th, 10th, and part of the 11th, now reaching the plateau, were accompanied by certain active senior officers who were able to give direction even in the complete confusion of the plans. Many belonging to the first six companies, when they reached the first height, had a notion that their work as a covering force was done. After the acute tension in the boats, they arrived on the plateau in bursting spirits. The excitement and surprise at being there and alive, having more than half completed the formidable task which had hung over them for six weeks, drowned all other feelings at the moment. The dim forms of Turks were still running across the lower ridge which formed the southern continuation of the plateau (MacLagan’s Ridge). With a laugh and a shout the men blazed at them. To many the battle was more than half finished, and they naturally waited for directions.

The first ridge inshore was to have been the place for a swift reorganisation. It had been hoped that there would be time for the companies from the destroyers to join those from the battleships at that point. On the northern arid highest corner of the plateau, Brockman, being a senior major of the 11th, was sorting men of the three battalions, sending the 9th to the right, the 10th to the centre, and keeping the 11th on the left. He forbade the men with him to fire at the Turks who were fleeing over the same ridge only a hundred yards or so to their right. The 9th and 10th, clambering over the ridge further south, would deal with them.

Only a portion of the battleship tows of the 11th had reached Plugge’s Plateau. Others, as will presently be told, had made their way into the valley further north. But almost the whole of the battleship parties of the 9th and 10th were now on the plateau. Colonel Weir, with Oldham's and Jacob’s companies of the 10th, reached the plateau more or less together on the right of the 11th. After firing for a few minutes from the summit at the Turks running below, these companies led on into the valley, heading for the path up which the enemy were making.

The two companies of the 9th, which should have been on the right of the 10th, had been mixed up with the 10th and with each other by the swing of the tows. The rush up the hill had disorganised them, though not beyond the possibility of restoring order. But they were without senior officers. Major J. C. Robertson had been hit on reaching the plateau. Major S. B. one of the 9th’s company commanders, found his way with a few of his men to the far left and was killed later in the day on Baby 700. The colonel was not on the plateau.

But the medical officer of the battalion, Graham Butler, had led some of its men up the hill, and its junior major, Alfred George Salisbury, managed to keep his own company and part of Major S. B. Robertson’s fairly well together on the top. Salisbury took charge of the right, and gave Captain Ryde the left. No senior officer was present to order the advance; but when, almost immediately after the main portion of the 10th had plunged into the valley, Salisbury saw the Turks doubling down the same valley to his right, he gave the word to move into the gully after them. For the rest of that day, until the 9th Battalion ceased to exist as a fighting unit, it was this young officer who commanded it.

This left only the 11th, organising under Brockman, at the northern end of Plugge’s. But the second instalment of the covering force was already ashore and making inland. Some of the Turks whom Salisbury saw running away on his right, and those whom Brockman had observed bolting back over Machlagan’s Ridge when he prevented his men from firing at them, were fleeing before the second portion of the landing force-that which was being brought in by the destroyers.

The destroyers, as soon as they received the word to go in and land their troops, had moved swiftly to their work. They were towing the boats of the transports, empty except for the few seamen and soldiers who were to work them as crews. One of the boats beside the Foxhound, containing two seamen and seven men of the 10th Battalion, began to steer wildly. The seaman at the tiller could not control her. She slewed in, then out, and began to tip. Someone shouted: “Pace too fast for Number Two boat!” But it could not slacken. The seaman put the tiller over, and the boat slewed in again close below the destroyer’s side. The ship’s rail was crowded by men of the 10th looking down upon their comrades. The boat tipped inwards, the water washed through it and swept every man clear over the stern except the helmsman, who caught the stern rope and began to crawl back along it into his boat. He had his leg over her side when she swung in again and crushed him against the destroyer. The next instant six or eight seamen had cut clear the overturned boat and hauled in the helmsman, hurt beyond all hope. It was no time to save men; the pace could not even slacken. Lifebelts were thrown over. Some of the men may have been picked up. Those in the transports, already gliding in, looked down curiously at an overturned boat two miles out on the glassy surface.

The destroyers held close in to land, then slowed, and edged about for a moment, 500 yards from the shore. The commander of the Colne shouted to his neighbour through a megaphone to shift southwards, as they were too far north. A flat coast-the point of Suvla Bay-could just be seen to the north, when a bright light appeared ahead; then came a shot and a succession of shots. Far astern, in a fleet of transports moving up four by four unseen through the grey veil of dawn, thousands of watchers also saw that light. “They must be signalling from the shore,” they thought A minute later the faint knocking, as of a wagon’s axlebox heard ever so far through the bush, came to their ears; at first single knocks, then a continuous sound like the boiling of water in a cauldron.

It was some minutes before they realised that it was the sound of desperate fighting in the dark. They could only wait, powerless to help or to discover how their comrades fared.

With the destroyers, as the first shots were fired, the rowing-boats were being hauled alongside for the men to disembark into them. Bullets had begun to fly over, but the high forecastles of the small warships against which they pattered partly shielded the decks. In the Ribble Commander Wilkinson, quiet as ever, gave the order: “Man the boats, men!” A low improvised wooden staging, like the step of a tram, had been fixed round the ship’s side. The men stepped down from this into the boats. A steamboat, returning from the battle ship tows, said: “Can we give you a tow?” and picked up some of the Ribble’s boats. At the first attempt only one boat got away with her. She turned round to pick up some others, and this time the last boat caught in the destroyer’s anchor and the tow-rope carried away. Finally the steamboat made off with the first tow. The destroyers were obliged to wait for the boats to return before they could clear all their troops. The delay seemed ages long. Four men in the Ribble had been hit while they waited; one of these fell forward into the water and his heavy equipment drowned him, despite all the efforts of one of the seamen. Finally the boats began to return one by one. “Here you are; you can get into that,” said Wilkinson to some of the 12th, as a steamboat came alongside with a big barge. “Good-bye and good luck!” cried a naval sub-lieutenant leaning over the side. As he spoke, he fell shot through the head.

The destroyers, like the battleship tows, landed their men north of the intended spot. They did, however, set them ashore in the proper order: 9th on the south, 10th in the middle, 11th to the north, and a portion of the 12th with each. These landing parties were far more widely distributed than the battleship tows. The southernmost destroyer was three-quarters of a mile south of Ari Burnu, the point where the earlier flotilla had landed; the northernmost was 300 yards north of that point. The first tows from each destroyer reached the land while it was still too dark to see a man at fifty yards. The majority came in at points which the battleship tows had not touched. A party of the 10th Battalion, under Lieutenant Loutit, who had three men killed in their boat coming in, and several other boats of the 10th, struck the beach half-way between the two knolls. Flashes of the Turkish rifles were still visible on the edge of the plateau above; there were also, at this part of the shore, Turks on the beach and in the scrub immediately above it who fired at point-blank range as the men landed. The landing effected, these Turks ran up through the scrub, but the Australians could not prevent their escape; their own bayonets were not yet fixed, nor their rifles loaded. As soon as that had been done, this second instalment of the 10th rushed the slope a hundred yards or two south of the first rush. The enemy fleeing before this charge were the same that had been seen by the Australians when reforming on the plateau.

The destroyers carrying the 9th Battalion were the Colne and Beagle. The Colne, with Captain Jackson’s company, after some manoeuvring landed her tows a quarter of a mile south of the 10th, immediately beyond the smaller knoll (Little Ari Burnu, above Hell Spit), close to where the valley behind Plugge’s bent round to the sea. The tows of the Beagle, with Captain Milne’s company, came in a thousand yards to the south of this again, near the big hill which forms the southern side of the same valley - part of the “400

Plateau.” On the first alarm the Turks on Gaba Tepe at once sighted the Beagle, and opened upon her with every rifle and machine-gun. The range was long, but one machine-gun had it accurately. Its shots pattered on the high bows of the destroyer like hail on an iron roof, and the water through which the boats had to move was whipped to spray by bullets. Where Milne’s company landed, the seaward slope of the 400 Plateau ended in a low cliff. There were Turks in cover within sixty yards of the beach, some in the low scrub and some in trenches, firing on the boats. The Australians dumped their packs on the beach, and then rushed the nearest of the enemy. The Queenslanders were strong and fit, and they went swiftly up through the scrub. Half-way to the top, Milne’s company found Jackson’s company already coming across from the north side of the valley to join it.

Jackson’s company, which landed at Little Ari Burnu, had the duty of reaching Gaba Tepe, and on landing it strove to carry out its instructions by charging over Little Ari Burnu and bearing southwards. A desultory rifle fire was coming from the slopes ahead of it. As the company moved down the back of Little Ari Burnu into the valley, it found a small stone hut, in which were half a dozen Turks and a small fire with a pot of coffee upon it. The Turks were bayoneted. The company went on up the slope of the 400 Plateau a few hundred yards away, south of the valley, where it joined Milne’s company. With these were advancing, under Captain Whitham, portions of the 12th Battalion, which had been carried in the southernmost destroyers. From Plugge’s all these troops could be seen, in the growing light, working inland through the scrub along the hill slope.

These companies .from the destroyers had landed twenty minutes after the battleship tows. But the heights above their landing-place were easier than the side of Plugge’s; their path inland was more direct and less precipitous. The result was that Milne’s and Jackson’s companies of the 9th, and some portions of the 10th and 12th, although they were behind Salisbury’s companies in the time of their landing, were slightly ahead of him in making inland.

Leaving these troops beginning their advance on the right, it becomes necessary to turn to the left, or northern, flank of the covering force.

The northernmost of the destroyers, carrying part of the 11th and 12th Battalions and the 3rd Field Ambulance, landed their men on the semicircle of shore north of Ari Burnu, a few hundred yards further north than any of the battleship tows. In front of them a small area of rough ground was shut in by bare yellow precipices rising at 300 yards from the beach. The central cliffs, their gravel worn and fluted by runnels, stood sheer to 400 feet, a few tufts of scrub catching a precarious foothold on their face. The ridge led down to the beach only in two places - at either side of the semicircle - by the steep slopes of Plugge’s on the right, and by a rugged tortuous spur (afterwards known as “Walker’s Ridge”) on the left. Between the two, exactly in the middle of the semicircle of cliffs, there had once been a third spur, but the weather had eaten it away. Its bare gravel face stood out, for all the world like that of a Sphinx, sheer above the middle of the valley. Its feet rested on the scrubby knolls below, and the two semicircles of cliff swept round on either side of it like wings.

It was this place which had struck every observer as impossible of attack. The Turks knew its central precipice as Sari Bair (the Yellow Slope); but the War Oflice map transferred that name to the whole ridge of Koja Chemen Tepe. To the Australians from that day it was the “Sphinx”.

It was on the small semicircle of shore enclosed in this partial amphitheatre - Walker’s Ridge - The Sphinx - Plugge’s Plateau - that the tows from the destroyers carrying part of the 11th and 12th Battalions came to land. The Turks on this northern flank had been thoroughly awakened by the arrival of the battleship tows further south on Ari Burnu a quarter of an hour before. The northward Turks had not been embarrassed by any attack, and were fully prepared and in their trenches. Before the boats left the destroyers, bullets were rattling against the high bows of the warships. The rowing- boats were under heavy fire all the way to the shore; and as the foremost of them reached the land, the first Turkish shells came singing over from Gaba Tepe. An unseen Turkish machine-gun was firing from somewhere on the lower slopes of Walker‘s Ridge or of the foothills north of it, under which were marked on the map the Fishermen’s Huts. Rifle fire was coming from that direction, and also from some trench near the edge of the cliffs by the Sphinx.

Bullet after bullet went home amongst the men in the crowded boats. Here again the figure of a midshipman standing up in the stern of one of the Devanha’s cutters set an example remembered by all who saw it. In another boat, carrying some of Captain Tulloch’s half-company of the 11th Battalion under Lieutenant Jackson, six were hit before reaching the shore, and two more as they clambered from the boat. These two were hurriedly pulled by a third man into the shelter of the bank which bordered the beach. The men rushed across the beach and lay under this bank or in a small creek running down from the slopes south of the Sphinx.

The tows of the 12th Battalion and of the 3rd Field Ambulance from the Ribble touched the shore almost opposite this gutter, under fire at short range. Shots were striking the water. Here a man scrambled out over the stern of a boat, found the water too deep for him, tried to hang on to the boat, and presently dropped off. There the oars of a boat floated away, and Lieutenant of the 12th Battalion waded about endeavouring to pick them up. Colonel Hawley, second-in-command of the 12th, was getting into the water, when he was hit by a bullet in the spine. In the 3rd Field Ambulance three men had been killed and thirteen wounded before they could reach the bank.

The fire from the left was very heavy, even upon those who, further south, were lining the bank of the beach north of Ari Burnu. At this juncture the general order to the troops after gaining the shelter of the bank was to strip packs, leave them under the bank, open cut-offs, load ten rounds, and pull back safety catches. Bullets were whipping in among the men who were sheltering, and, when Colonel Clarke landed from the destroyer, many of the men of the last battleship tow, who had arrived barely ten minutes before, were still there. With them was Captain Peck, adjutant of the 11th Battalion. Peck’s place was with his Battalion Headquarters, but, being unable to find it, he reported to Colonel Clarke of the 12th. Captain Everett, Lieutenants Jackson, Rockliff, and Macfarlane, of the 11th Battalion, and Lieutenant Rumball, of the 10th, were under the bank, and with them a number of men who had been heavily tried in the landing.

“Come on, boys … By God, I’m frightened!” said Peck, and started off inland through the scrub towards the cliffs above. With Rockliff, Macfarlane, and Jackson, he soon outstripped Colonel Clarke, who climbed a scrubby knoll below the Sphinx, and there waited.

The orders to the 12th were to assemble as reserve to the 3rd Brigade at the foot of the 400 Plateau, and send a platoon to escort the mountain battery which was to take up its position early on the top. But the 400 Plateau was a mile south, behind cliffs apparently impenetrable. Clarke waited on the knoll, with the intention of collecting his northern companies, which were coming ashore in relays.

But the transfer from the destroyers was slow. The light was growing. The machine-gun from the left was harassing the boats. After waiting for the second tows, Clarke decided that there was only one thing to do - to push on up the cliffs in front and leave the rest to follow. Lieutenant Rafferty, whose platoon was to have escorted the Indian Mountain Battery on the 400 Plateau, Clarke ordered to move to the left and silence the machine-gun. Rafferty reminded the Colonel that his orders were different. “I can’t help that.” was the reply. Lieutenant Strickland, with a platoon of the 11th. which had landed with the battleship tows, had been ordered to proceed along the edge of the beach and combat the same fire. Rafferty was to work next to him, inland.

One destroyer landed its tows yet further north, in the same enclosed semicircle, but near to the foot of Walker’s Ridge. These carried half a company of the 11th under Captain Tulloch and some of Captain Lalor’s company of the 12th under Lieutenant EY Butler. A machine-gun on some height beyond Walker’s Ridge was playing on them. They therefore sheltered in a creek bed about eight feet deep and thickly timbered, only to find shots coming down it from their flank. In consequence they moved along a goat track leading through holly scrub knee-deep up the foot of Walker’s Ridge. The ridge narrowed, and became steeper and more bare. Shots whizzed past them from above and from the wild tangle of loftier scrub-covered gullies on their left. The file of climbing men dodged from cine side of the ridge to the other, until, far up the spur, it reached a small steep knob, above which the spur dipped for twenty feet and then rose again. To cross this dip every man had to run fifteen yards, completely exposed to fire from Turkish rifles on the higher spurs close to it on the north. After a fight of some sort, Tulloch’s party rushed to a smaller knob on the right, and thence made its way out on to the plateau (afterwards known as Russell’s Top) above the Sphinx.

A little to the right of them, near the far side of the long narrow Top was a line of men - Australians. A white track led along the further edge. A hundred yards from Tulloch, by the side of this track, someone was bending over the body of a dead Australian. The dead man was Colonel Clarke.

It has already been said that, when the second tow from the Ribble landed-some men in it, including Lieutenant Margetts, going neck and shoulders under in the deep water-Clarke decided that he could not wait for the third tow. Margetts, after getting his men to lie down under the bank, caught sight of the Colonel standing on a knoll some distance inland. Clarke saw him and called: “Bring your men up here.” The men came up in single file; officers had learned that their first duty was to find the enemy. Margetts climbed to the Colonel’s side, and scanned the heights for anything to shoot at. It was dull grey dawn. Margetts pulled out his glasses, but the lenses were wet with sea water. He tried to wipe them, but the clothes of all were drenched to the neck. On the flat below at that moment Lieutenant Rafferty, who had been sent with his platoon to silence the machine-gun, was endeavouring to do exactly the same thing. Rafferty tried his handkerchief, and then the tail of his shirt; but both were soaked. Lieutenant Patterson was beside Clarke and Margetts on the knoll. As they could find nothing, the Colonel sent them to attempt with their men the passage of the bare precipice south of the Sphinx. The earth of the landslides at its foot gave some hope of a foothold.

Margetts and Patterson were young and active men - Margetts a schoolmaster, Patterson a Duntroon cadet. Despite their youth and strength, it was all they could do to reach the top, hauling themselves up on hands and knees along a slant south of the Sphinx. Odd parties of the 11th and 12th Battalions were scrambling up these gravelly and almost perpendicular crags by any foothold that offered. Captain Peck had already gone that way with Captain Everett, Lieutenant Rockliff, Lieutenant Jackson, and some of their men, but in the wild country near the Sphinx they became separated. One of this party, Corporal EWD Laing of the 12th Battalion, clambering breathless up the height, came upon an officer almost exhausted half-way up. It was the old Colonel – Clarke - of the 12th Battalion. He was carrying his heavy pack, and could scarcely go further. Laing advised him to throw the pack away, but Clarke was unwilling to lose it, and Laing thereupon carried it himself. The two climbed on together, and Margetts and Patterson, reaching the top, found to their astonishment the Colonel already there.

As the party scrambled to the level of Russell’s Top, they discovered before them a slight rise in the crest, and over the edge of it, to their delight, beheld their first Turk. Near the Sphinx was a trench full of them.

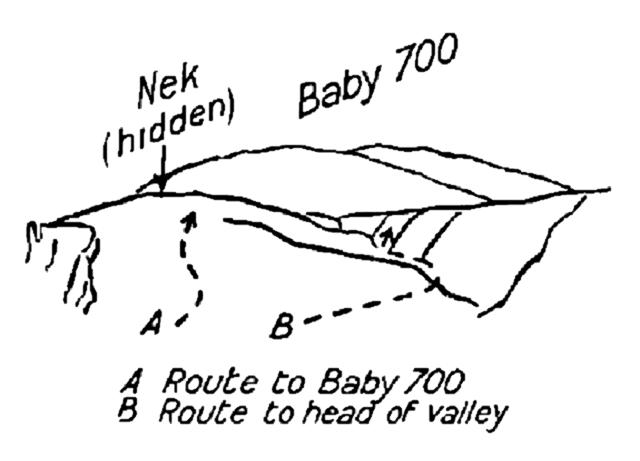

About fifty men had reached the Top. With one leap they all ran forward-Margetts ahead, pulling out his revolver, in the hope of getting there first. The Turks scrambled over the back of their trench and fled. Colonel Clarke shouted from behind: “Steady, you fellows! Get into some sort of formation and clear the bush as you go.” The men did so, forming a rough line with about three paces interval between them. Presently they reached the trench - a straight cut in the ground running across the Top like a neatly-opened drain, with the parapet carefully flattened and covered with dry bushes, which had faded to a shade of pinkish brown. Every trench seen in the hills at this date was constructed in the same manner, and men came gradually to know by bitter experience what was meant by a brown streak through the scrub in front of them. No Turks remained in the trench, and no communication trench led into it. Only a well-worn white track ran off up the narrow Top, winding to the right across a saddle between the valleys on either side, to a long hog-backed slope half a mile away. That slope they soon realised to be the “Baby 700’’ of their objective. The neck between it and the Top has become famous in Australian history as “The Nek.” Over The Nek along this track were bowling the Turks - a string of thirty of them in brown khaki uniforms, their shins muffled in heavy wrappings. Two or three were shot as they ran. The rest presently sank into the scrub about 1,000 raids away on the seaward side of Baby 700 and there made a line. With them was an officer, and every Turk appeared to be jabbering.

Colonel Clarke and his men, making no stop in the trench, moved beyond it to a point near The Nek, where another small track, coming out of the valley on the right, crossed the Top and went steeply down to the valley on the left. The men lay down along this track, Margetts in charge of the left, and Patterson on the right. Across the head of the narrow valley to the right (the same into which the troops looked down from Plugge’s Plateau) there were Turks in the scrub and in trenches firing on them at 350 yards. Colonel Clarke was anxious to send a message to Colonel MacLagan, in command of the covering force, telling him where the 12th Battalion was. He was standing by the track, writing in his message book, when he fell with the pencil in one hand and the book in the other. The Colonel’s batman, who was ready to take the message, fell dead with another bullet. Major Elliott, second-in-command since Hawley had been hit, was called for and came up. He immediately fell shot through the shoulder. Margetts was sent for, but Elliott, lying on the ground, shouted to him: “Don’t come here! It’s too hot !”

Margetts and Patterson had only fifty men. They decided not to advance further at the moment. Presently the fire from the position which the Turks had taken up in the scrub ceased. Possibly Tulloch’s party, seen working up Walker’s Ridge, had scared them. Margetts sent two of his best scouts, Tilley and Vaughan round over the neck to Baby 700 to see if the enemy had gone. The two men could be seen presently signalling back with their arms by “semaphore” that the way was clear. Meantime Lieutenant Burt, of the 12th, had come up with more men, and he decided, according to the rules learnt again and again at Mena. to reorganise those present into platoons and sections under officers or sergeants. They withdrew a little to a hollow on the Top, and there found Tulloch and his men. The two parties reorganized. Officers were told off to take charge of the platoons, and non-commissioned officers to take charge of the sections. The line then went forward at two paces interval.

Russell’s Top narrowed after passing the point where Walker’s Ridge joined it The valley on the left, beyond Walker’s Ridge (later known as Malone’s Gully), came in very rough and steep; the valley on the inland side ran gently to a spoon-shaped head. Between the two, leading to the long back of Baby 700 which rose beyond, the Top narrowed to The Nek. This was about twenty yards wide from slope to slope at the narrowest point. As they approached The Nek, after passing for the second time the cross track on which Colonel Clarke had been killed, Lieutenant Burt told Margetts to stop a little short of The Nek and entrench. At that moment there came up under Captain Lalor another party of the 12th Battalion, which also had climbed the cliffs not far from the Sphinx. They had now about three-quarters of Elliott’s company of the 12th and half of Lalor’s, besides a platoon of Tulloch’s company of the 11th. The 12th was supposed to be in reserve, and Lalor decided that the holding of this marked neck on the left flank of the covering force was too important to justify a further advance by the reserve troops at that moment. Tulloch with his handful of the 11th went on, while Lalor set his men of the 12th to dig a semicircular trench just short of The Nek, with its flanks looking down into the valleys on either side. Far behind them, down the valley on their right, they presently saw men who had crossed from Plugge’s digging furiously along the opposite crest. It was about 7 o’clock. The sun had risen in a clear blue sky. Far out the transports, gliding in four by four, trailing the long threads of their wash over the silky lemon- coloured sea, had long since begun to land their troops.

Colonel MacLagan, the commander of the covering force, and Captain Ross, his staff-captain, had come ashore with the first tow of Jackson’s company of the 9th from the destroyer Colne. Major Brand, the brigade-major, who was in another rowing-boat, saw them land on the beach a little north of him. Brand went to his chief and it was arranged that he should make straight inland towards the right front to take charge of the situation there, while MacLagan and Ross climbed the ridge above the beach - the southern shoulder of Plugge’s. From that time onwards the ridge bore MacLagan’s name. Brand hurried off, taking with him Lieutenant Boase of the 9th, who had landed with him, and his platoon. MacLagan and Ross toiled up an almost perpendicular gully to Plugge’s.

As MacLagan reached the plateau, he realised that the landing had been made in the rough country a mile north of the proper place. The officers of the Colne had known it, but it was then too late to change. Half a mile to the right front, across the valley into which Maclagan looked from Plugge’s, was the lump of the 400 Plateau where should have been his centre. Australians could be seen beginning to make their way through the scrub on the near side of that plateau. The 9th and 10th had already left Plugge’s when MacLagan reached it, and their companies were working towards the right front, apparently trying to carry out the original plan If it was to he achieved, that was the sector in which a commander was needed.

Brand had already gone in that direction. Before MacLagan himself moved across to grapple with the problem presented there, he gave a few swift orders to the 11th, which was organising close beside him on Plugge’s and below it. The 11th was responsible for the left of his force. On that side was the valley in front of Plugge’s reaching to the foot of Baby 700. There were already some troops in that direction, now under Lalor; but little was known of them. MacLagan decided to hold the far side of the valley and Baby 700 at the end of it. He gave rapid directions to the company commanders who were organising their troops on the plateau, pointing out to them various landmarks on the far side of the valley or at its head, and directing them towards these. In addition to the large portion of the 11th Battalion which was being organised by Major Drake Brockman, MacLagan had beside him Major Hilmer Smith’s company of the 12th, which had just scrambled up the hill on his right. He told Smith to take his company due-east-straight to the opposite side of the valley. Brockman he directed northwards, to occupy with the 11th the head of the valley and Baby 700.

[From: Bean, p. 276.]

The first part of the latter order was fairly easy to carry out. The far side of the valley near its head was indented by four shallow gullies or landslides, like the flutings of a column, up which troops could probably work. MacLagan directed that detachments should occupy the summit of these indentations and so make sure the far side of the valley. But the despatch of other detachments to Baby 700 was far from being so simple as it appeared. The Nek and the branch of the valley which ran into it were not visible from where MacLagan stood, and were not shown on the maps. Russell’s Top, which rose just north of Plugge’s, appeared to be a continuous spur leading up to Baby 700 and the larger hills beyond it. To reach Baby 700 part of the 11th was to move up this spur, while other parts were to mount by the head of the valley.

When the first troops had reached Plugge’s, some of them, hurrying after the Turks a hundred yards across its northern end, found themselves looking down sheer yellow slopes into two spoon-shaped valleys divided, immediately beneath where the men stood, by a yellow sandy ridge with an edge too sharp to allow a man to walk safely. The ridge led like a causeway to Russell’s Top, which rose gradually two hundred yards away. The valley on one side sloped between the Sphinx and Plugge’s to the sea; that on the other side opened into the main valley inland of Plugge’s. A month later, because of their security from shell-fire, these two gullies began to be used by troops in reserve, and were named, the seaward one “Reserve Gully,” the inland one “Rest Gully.”

A part of the 11th which, as has been mentioned, had arrived with a battleship tow rather later than the rest and had made inland with Colonel Clarke and Peck, had climbed straight over this razor-edge into Rest Gully and was collecting there. Peck, being adjutant, had left Rockliff and Macfarlane in charge of these men and had disappeared inland in search of the headquarters of the battalion. Presently Everett, with part of Brockman’s company, of which he was second – in - command, also arrived in Rest Gully. Brockman had been organising the other half of the company on the top of Plugge’s Plateau. As the men were under a scattered rifle-fire, and were separated from Everett’s half, Brockman moved his half-company down into Rest Gully, so that it might reorganise together with the other half in shelter on that side of the gully which led up to Russell’s Top.

Like most of the other troops that day, they descended from Plugge’s by the steep zigzag path beside the three tents. At the bottom, in the sand of the gully, was a fingerpost with a red sign and Turkish lettering in black. Near it was a pick handle, stuck into the sand. The post was almost certainly a direction stating that the path led to a company post of the 27th Turkish Regiment on Ari Burnu. But the suspicion that the enemy would leave his tracks and trenches mined led men to avoid the spot. The red signpost was taken as ail indication of a mine, and a sentry was put near the pick handle to warn men against touching it.

While Brochman’s company was reorganising on the further slope of Rest Gully there was heard a sharp whine through the sky. A pinpoint flash high above the razor-back, from which a small cloud as of white wool unrolled itself; a report like that of a rocket; a scatter of dust on the bare side of the razor-back below-it was the first Turkish shrapnel shell that these men had seen. For the next ten minutes the Australians in the Turkish trenches on the plateau, and the men reorganising in the gully, were fascinated by this new wonder.

The shell was from Gaba Tepe, where the battery had already begun to fire at the boats and at the beach. As guns came up elsewhere during the day, salvoes of shrapnel began to burst continually in the valleys inland of Plugge’s. Several of these consequently became known as “Shrapnel Gully,” but within three days that name had fastened definitely upon the main valley into which the first troops looked from Plugge’s. The first Turkish gun had opened at 4.45 a.m., fifteen minutes after the landing. There was the flash of a gun on the inland neck of Gaba Tepe, and a shrapnel shell burst near the beach. The first destroyer tows had just landed. Two minutes later the guns of the battleships began to reply, but the Turkish battery near Gaba Tepe was not quelled by their fire. As the transports of the 2nd and 1st Brigades moved in, the small guns at Gaba Tepe sought to reach them, but the shrapnel pellets pattered into the water short of the ships. When the destroyers, after landing their original loads, came back to take the troops from the transports, the guns opened both upon the destroyers and upon the rowing-boats about them. The cruiser Bacchante was firing regularly at the flashes. Her shells were high explosive - that is to say, they hit the ground before they burst, and depended for their effect upon the powerful explosive, which scattered abroad deadly fragments of the shell-case and tore great clouds of dust and earth from the neck upon which were the Turkish guns. The Turks were firing shrapnel - a shell which is timed to burst in the air, and which, like a shot-gun, projects a number of ready-made pellets upon the ground below. Though the Bacchante’s broadsides appeared to fall upon the Turkish battery, it continued to fire.

A little before 7 a.m. the Bacchante moved slowly shorewards, until she was poking her nose fairly into the bay opposite the guns, and thence she fired at them broadside after broadside. They became temporarily silent. Yet every time a destroyer ran in to discharge her troops, a salvo from the battery sang over them. It was immediately answered by the Bacchante broadside, and again became silent. When the next destroyer ran in with her troops, it invariably opened again.

The men of the 2nd and 1st Brigades in the transports, which moved in between the battleships before the dawn, had been raised to a high state of excitement by the Bacchante’s shooting. “By gum, that’s pat!’’ shouted a private of the 1st Battalion on the Minnewaska’s well-deck, as he rushed to the side waving his cap. The Turkish battery strove to reach the transports as soon as it sighted them - which was about 5.10 a.m. Several shrapnel shells sang fairly close, and the pellets pattered in the water short of the ships. “Look, mate,” said another man of the 1st Battalion, “they’re carrying this joke too far. They’re using ball ammunition!” From the moment when they neared the first sight and sound of action, a marked change, noticed by every officer, came over these troops: they were straining like puppies on the leash, eager to be in the fight. Meanwhile, in the Minnewaska’s saloon, the officers’ breakfast was proceeding, the flashes of the warships’ guns every now and then showing through the portholes. The oldest steward had swept the carpet as usual, and, napkin on arm, was placing the menu before his passengers and asking if they preferred eggs or fried fish after their porridge.

Until 7 a.m. those in the transports had no idea as to whether the landing had succeeded. The constant burst of shells on Plugge’s, and the small boats far ahead - returning singly and rather aimlessly from the beach, gave the impression that fighting was still heavy near the shore. About 7 o’clock, in the growing light, the anxious watchers along the ships’ rails made out the forms of men digging, walking, and apparently talking together unconcernedly upon the high ridges ahead.

There was no mistaking that casual gait - it was a sure sign throughout the war. They were Australians. Lines of them were digging in on the first and second ridges beyond the beach. The 3rd Brigade had established itself on the land. Between 5.30 and 7.30 the 2nd and 1st Brigades of the 1st Australian Division began to move.

Further Reading:

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, AIF, Roll of Honour

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, Bean's Account, Part 1