Topic: BatzG - Anzac

>

The Battle of Anzac Cove

Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

Aspinall-Oglander's Account, Part 2

The following is an extract from CF Aspinall-Oglander, Military Operations, Gallipoli, Volume 1, 1929, pp. 181 - 200.

CHAPTER X

THE LANDING AT ANZAC - THE MAIN BODY

Colonel JW M'CAY, commanding the 2nd Australian Brigade, landed about 6 o'clock. On learning from Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan, whom he joined on First Ridge, that the right was in imminent danger and might be turned at any moment, whereas the left was comparatively secure, he agreed to place his brigade on the right flank. The two brigade commanders then proceeded independently to 400 Plateau, Sinclair-Maclagan going to its northern end, and M'Cay to the spur afterwards known as M'Cay's Hill, where he decided to establish his headquarters. From this point he examined the ground over which his brigade was to be employed, and, impressed by the importance of Bolton's Ridge as a position for guarding the right flank of the landing places, he issued orders for the few men already in that locality to be strongly reinforced as soon as troops became available. It was decided that the dividing line between the 2nd and 3rd Brigades should be a line running east and west across the centre of 400 Plateau, through Owen's Gully.

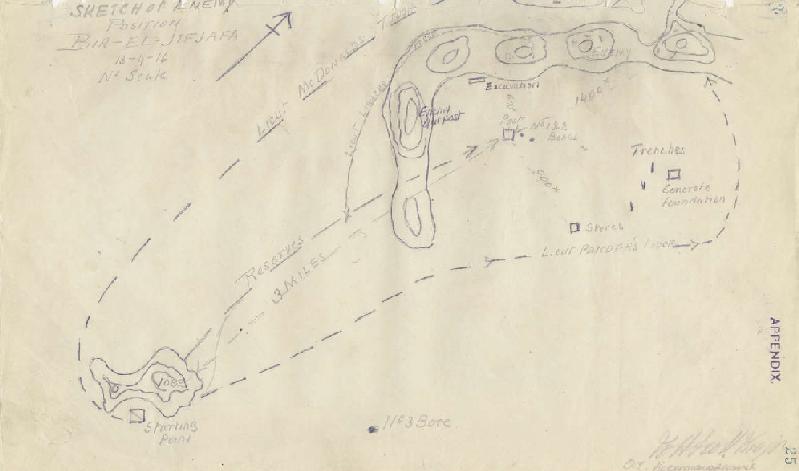

By this time-about 7 o'clock-the sun was high in the heavens, and it was a perfect spring day. With the exception of a few snipers all opposition on Second Ridge had ceased, and scattered groins of Australians were in undisputed possession of the crest, including the eastern slopes of 400 Plateau, and the long pine-covered spur-Pine Ridge-at its south eastern extremity. A few small parties, led by very gallant officers, had even succeeded in reaching various points on the western slopes of (Jun Ridge, the final objective of the covering force. In particular, Lieut. Loutit, of the 10th Battalion, had actually penetrated with a couple of scouts as far as Scrubby Knoll, whence he could see, only 3½ miles away, the gleaming waters of the Narrows – [This was the nearest point to the Narrows reached by any Allied soldier during the campaign.] the goal of the whole campaign.

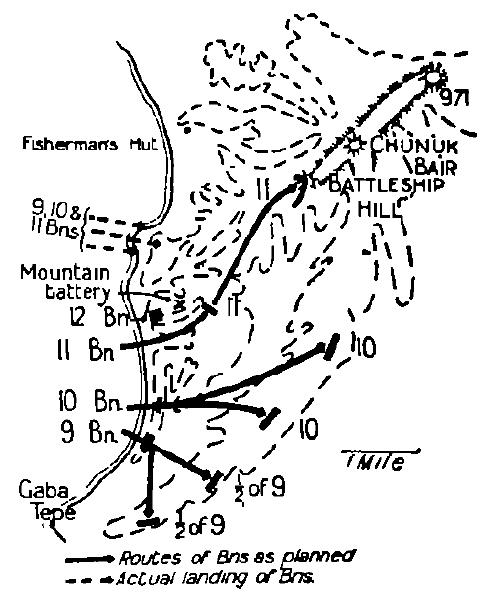

But these gallant advanced parties could progress no further till reinforced, and owing to the intricate country this urgently required support was not forthcoming for the moment. The disastrous swing of the tows had upset every carefully laid plan for the battle. Much time had already been lost, and the precious hours during which Gun Ridge was almost undefended were remorselessly ebbing away.

When Sinclair-Maclagan reached 400 Plateau he found a number of his troops on its western side in disconnected detachments and a few posts on its eastern edge; but the thick scrub and precipitous slopes had completely disrupted the organization of his battalions. In these circumstances, unaware that any troops had already penetrated to Gun Ridge, he decided that, with his brigade so dislocated, it would be unsafe at present to make any attempt to occupy the wide frontage allotted to him on that ridge, and that the line of Second Ridge must for the moment be held as a covering position. He accordingly issued orders for the western edge of 400 Plateau to be entrenched, and also the positions occupied by detachments further north, on the crest of MacLaurin's Hill. [At Steele's and Courtney's. The important post at Quinn's had not yet been occupied, and a wide gap existed between Courtney's and the troops on Baby 700. The approach to both these posts, which were situated at the head of narrow indentations in the western side of Monash Gully, was exceedingly steep-that to Steele's being a mere landslide up which men could barely scramble on hands and knees.] The detachments on the eastern edge of the plateau were meanwhile to remain out in observation till the trenches behind them were complete.

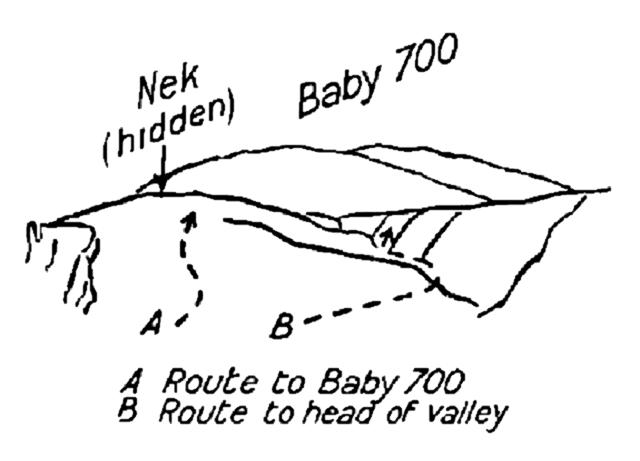

On the extreme left at the same hour - 7 am - though, owing to the difficult nature of the ground, Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan was not aware of it, the situation was no less confused, and the consequent delay in reinforcing the advanced troops no less disastrous. The troops on Russell's Top and at the Nek still consisted only of scattered fragments of all four battalions of the 3rd Brigade. Casualties amongst their officers had been heavy, and though by this time a small party under Captain Tulloch had crossed the Nek and reached the lower slopes of Baby 700, so much confusion and uncertainty had been caused by the complete shipwreck of all the elaborate plans for each unit on reaching the shore, that supports were long in reaching him. Here, too, precious hours were slipping away, and the attack was being held up by a small number of well-concealed marksmen.

The transports of the 2nd and 1st Brigades had arrived off the coast with clock-like precision, but the disembarkation of their troops was proving a troublesome matter. The shelling of the anchorage was increasing, and though the Bacchante stood close in to Gaba Tepe and raked the Turkish position with her broadsides, she was unable to silence its fire.

On the extreme left, the landing from the Galeka began disastrously. This transport, carrying the 6th and 7th Battalions, had been directed in its original orders to disembark on the left of the 3rd Brigade. Arriving off the shore at 4.45 am, the commander of the vessel steered to the north of Ari Burnu, and stood in to an anchorage some six hundred yards from the shore. Here for some time he awaited in vain the arrival of tows to disembark the troops. But none arrived, and as it was obviously impossible to remain for long in that exposed position, with shrapnel bursting above the crowded decks, it was decided to make a start by landing some troops in the ship's own boats. Six boats were filled with a company of the 7th Battalion, and the first four of these, steering for what appeared to be the left flank of the troops already ashore, headed straight for the Turkish post at Fisherman's Hut. For some time the Turks withheld their fire, but when the boats came within two hundred yards of the shore, so heavy a fusillade was poured into them that over a hundred of the 140 men they contained were killed or wounded before they reached the land. The survivors captured the post without difficulty, for the Turks bolted eastwards as soon as they jumped ashore. But these few men were eventually forced to retire on Ari Burnu, and only 18 out of the 140 succeeded in rejoining their battalion during the day.

After this unfortunate episode all the infantry of the 2nd and 1st Brigades were taken to Anzac Cove, which now became the main landing place for the whole corps. But the majority of the transports anchored a long way out to avoid the shelling from Gaba Tepe, and the consequent delay was considerable. It had been hoped that both brigades would be landed by 9 am, but, though most of the troops were ashore soon after that hour and some of them a great deal earlier, it was one o'clock before the last battalion' of the 1st Brigade had completed its disembarkation. A contributory cause of this delay was a disregard of the orders for the evacuation of the wounded. The naval beach personnel had been instructed that the evacuation of wounded was to be carried out only in medical boats specially detailed for this purpose, and that the tows engaged in landing the fighting troops were on no account to be used for wounded men. In the event, however, not only were men who were killed or wounded on their way to the shore not unnaturally left in the tows, but, owing to lack of organization on the beach during the early hours of the morning, [In accordance with naval and military orders, the naval and military beach personnel did not land till 10 am. This scheme differed from the procedure adopted at Helles where they landed with the second trip of tows.] the return of the boats was in many cases delayed while other wounded were embarked. As a result, still further delay occurred when the tows returned to the transports, for the troops for the next trip could not be transferred to the boats till the wounded had been lifted on board and the dead disposed of; and facilities for this work were in many cases non-existent. [A cause of delay in the return of the boats for their second consignment of troops was, in some cases, the enthusiasm of the boats’ crews. There were many instances of bluejackets rushing forward with the troops in the excitement of the moment when the boats first landed, and Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan reports that he himself sent several back to the shore.]

As each company of the 2nd Brigade and the leading companies of the 1st Brigade reached the shore, they were guided to a rendezvous at the southern end of Shrapnel Gully, but even here there was further cause for confusion. Owing to the change of plan there were at first no definite orders for any unit; many officers indeed were for some time unaware that the plans had been changed at all. Added to this, there were throughout the morning constant and often unauthorized calls for reinforcing companies to fill a gap in the line, which individual groups of high-spirited men would answer on their own initiative. As a result, and contrary to expectation, the leading battalions of both reinforcing brigades became scattered as soon as they arrived, and General Bridges' plan for keeping the 1st Brigade intact as divisional reserve was from the outset to prove impossible. To make matters worse, companies and platoons advancing independently up the main ravine frequently lost their way in one of its many branches, or found themselves called into an entirely different part of the line from that to which they had been despatched. Thus the units of the main body were soon almost as much intermixed as those of the covering force. The serious results of landing at so difficult a portion of the coast, and of the consequent unexpected delay in getting up formed bodies of reinforcements to the points where they were most urgently required, can best be gauged by a study of the Turkish movements during the morning of the 25th. According to the information available from Turkish sources the first news of the Australian landing did not reach Colonel Sami Bey's headquarters at Maidos till 5.30 am, or an hour after the landing had begun. For the moment, believing that the main landing would be at Bulair, Sami Bey was inclined to think that nothing but a minor enterprise was intended at Ari Burnu, but he ordered his two reserve battalions of the 27th Regiment and the machine-gun company to march at once towards Gaba Tepe to drive the invaders into the sea. It was 7.3o A.M., however, before these troops were ready to march, and 9 A.M. before they were seen by the advanced posts of the Australians, slowly filing up Gun Ridge from the south. Meanwhile the news of the Ari Burnu landing had been carried to Marshal Liman von Sanders about 6 am. But that officer, firm in his belief that the main attack would be made against the isthmus, had decided to remain at Bulair, and to allow, for the present, no weakening of his strength in that locality. Between 7 and 8 am, however, hearing of the further landings at Helles and Kum Kale, the Turkish Commander-in-Chief decided to send Essad Pasha, commanding the III. Corps, to take command in the south; and the commanders of the 9th and 19th Divisions were informed accordingly.

Shortly after the receipt of this message, and after the two battalions of the 27th had marched towards Gaba Tepe, a second report reached Sami Bey to the effect that the invaders at Ari Burnu, strength about one battalion, [The landing beaches were invisible to the Turks, and the fact that they placed the Australian strength so low seems to indicate that few men had yet succeeded in reaching the high ground on the left.] were advancing left-handed up the main ridge in the direction of Chunuk Bair. As the Helles area was by this time claiming his attention, he now asked the 19th Division, which formed the general reserve for the whole Dardanelles area, to detach one battalion to the Chunuk Bair ridge to guard the right flank.

Fortunately for the Turks, the commander of the 19th Division was none other than Mustafa Kemal Bey, the future President of the Republic; and that Man of Destiny was at once to show an outstanding genius for command. As soon as he heard that the enemy was making for Chunuk Bair he realized that this could be no feint, but was a serious attack in strength. Appreciating at once that it constituted a threat against the heart of the Turkish defence, he determined to examine the situation for himself, and to throw not a battalion but a whole regiment into the fight. Accompanied by an advanced party of one company, he set off in the direction of Chunuk Bair, ordering the remainder of the 57th Regiment to follow as quickly as possible. As already mentioned, the approaches to the main ridge were many times less abrupt on the inland than on the seaward side, and shortly after 10 A.M. this advanced party was in collision with Tulloch's small detachment in the neighbourhood of Battleship Hill. Mustafa Kemal remained on the spot long enough to issue orders for an attack by two battalions and a mountain battery as soon as they arrived. Then, having satisfied himself that the situation was temporarily in hand, he hurried back to Maidos to report to Essad Pasha. [Essad Pasha arrived at Maidos about noon. When Mustafa Kemal returned Essad approved his dispositions and gave him permission to use the whole of the 19th Division in the Anzac area. Hie then followed Sami Bey southward, to learn the situation in the Helles sector, leaving Mustafa Kemal in temporary command opposite the Australians.]

The time of the arrival of the main body of the 57th Regiment has never been fully established, but their mountain battery, which took up a position near Chunuk Bair, did not open fire till 1 pm, and the counter-attack down both sides of Battleship Hill did not develop till half-past four. It is probable, however, that, in addition to the detachment which arrived with Mustafa Kemal about 10 am, reinforcing companies began to trickle in to the Turkish position in that neighbourhood from midday onwards. A study of these figures will show that for several hours the Turkish troops available to oppose the Australian advance to Gun Ridge consisted only of the outpost company in and around Ari Burnu at the time of the landing, supported by such portions of the remainder of the outpost battalion, spread out over a five-mile front, as were withdrawn from their own posts to meet the attack. The delaying power of well armed and well-concealed marksmen, favoured by a perfect knowledge of the ground, is undoubtedly very great. Nevertheless there can be little doubt that the extreme difficulties of the country played an even greater part than the opposition of the enemy in frustrating the Australian plan, and that but for the unfortunate mistake in the landing place the 4,000 Australians who disembarked before 5 am and the 4,000 who followed them between 6 and 8 am could have pushed hack the Turkish outposts and established themselves on Gun Ridge and Chunuk Bair before the arrival of enemy reinforcements.

It was about half-past nine when the leading troops of the Turkish 27th Regiment began to advance westwards from the centre of Gun Ridge. The scattered detachments of Australians on the western slopes of the ridge were now forced to retire, and shortly afterwards a heavy and sustained rifle fire was poured by the Turks on to the summit of 400 Plateau and the crest of MacLaurin's Hill.

Fearing an immediate counter-attack on the eastern slopes of Lone Pine, Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan ordered the companies of the 9th Battalion, who were digging themselves in to the west of that locality, where the dense scrub prevented any field of fire, to hurry forward to meet it. Section by section the men were led forward through the scrub, but the volume of fire now being directed on the summit was much heavier than Sinclair-Maclagan had realized, and only a remnant of those who started succeeded in passing through it. Thus a gap was formed in the Australian front which throughout the rest of the day was a constant source of anxiety.

Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan had early decided to establish his headquarters on MacLaurin's Hill, and the brigade signallers had already chosen a position and connected it by telephone to the beach. When the brigade commander arrived there about 10 o'clock the Turks seemed to be threatening an immediate attack, and it was obvious that a break-through at this point would make 400 Plateau untenable. The decision not to advance beyond Second Ridge had had the effect of placing brigade headquarters in the firing line. But it was vitally important to hold MacLaurin's Hill, and the brigadier determined to stay in this exposed and in many ways unsuitable position in order to encourage his men.

Meanwhile on the extreme left flank, Captain Tulloch with about sixty men had reached the south-eastern slopes of Battleship Hill between 9 and z o o'clock, and had sent a small party under Lieut. SH Jackson to the seaward side of the hill to protect his left flank. Progress had been slow since passing the Nek, for though the Turks were few in numbers their shooting was deadly. In places it was nearly impossible to crawl through the prickly scrub; yet to show oneself above it for an instant was to attract a hot fire. Further in rear, on Baby 700, were other small parties under Captain JP Lalor and Lieut. IS Margetts of the 12th Battalion.

Shortly after 10 am the leading troops of the 57th Regiment, brought up by Mustafa, began to trickle into action on the seaward slopes of Battleship Hill, and first Jackson, and then the parties on Baby 700, were forced to give ground. A few minutes later a flanking fire was poured into Tulloch's party, and that officer, finding his left flank uncovered, was in turn compelled to withdraw. The retirement was only momentary, for shortly afterwards a company of the 1st Battalion [This battalion, landed at 7.40 am, had been ordered at 9.30 to reinforce 400 Plateau; but Swannell's company, becoming sandwiched in between companies of the 3rd Battalion, proceeded up Monash Gully to the left flank, lost its way, and at 10.15 found itself at the Nek.] under Major BI Swannell, swept over the Nek and recaptured Baby 700. But, away to the right rear, Sinclair-Maclagan, who had hitherto looked upon his left flank as reasonably secure, had witnessed with alarm the withdrawal from Baby 700 of Margetts, who also had been outflanked. At 10.35 am, expecting the Turks at any moment to appear on Russell's Top behind him, he informed divisional headquarters [General Bridges landed at 7.30 am and was now directing the battle from his headquarters in a gully on the seaward side of Plugge's.] that unless the Nek could be held he would be unable to remain on Second Ridge. He urged that reinforcements should at once be sent to the left.

For Major-General Bridges the situation was an anxious one, for the whole plan of the landing had evidently fallen to pieces. G.H.Q. had expected a semicircular position, including Gun Ridge, to be seized by a covering force of one brigade, preparatory to an eastward advance by the main body of the corps. General Birdwood had modified this order to the extent of authorizing the employment of a second brigade to assist the covering force by extending its left flank. But, despite this increase of strength, nothing but the unexpected had happened. The covering force had landed at the wrong place. The 2nd Brigade had been brought in on the right instead of on the left. Both brigades had become disintegrated. Since General Bridges' arrival on shore, eight of the sixteen companies of the 1st Brigade, which he had hoped to keep intact as divisional reserve, had already been rushed into the fight on Second Ridge. Of the remaining eight companies, six had not yet landed, and only two were available on shore to meet any further urgent calls for reinforcements. And now, at 10.35 am, the divisional commander was to learn that his left flank, which Sinclair-Maclagan had at first thought to be reasonably safe, was after all in imminent peril. Orders were at once issued for the two available companies to reinforce the Nek, and with their departure, except for the 4th Battalion and two companies of the 2nd which were still afloat, all the infantry of the division had been absorbed into the battle. Little progress had been made; only half of the covering force's task had been accomplished; the position was manifestly insecure; and the inevitable counter-attack had hardly yet begun.

At this critical juncture, about 10.45 am, General Birdwood signalled that he was landing one and a half battalions [The Auckland Battalion and two companies of the Canterbury Battalion. In the original plan no arrangements had been made to land this brigade till the disembarkation of the Australian infantry, with a proportion of artillery and ancillary services, had been completed. It is possible that the change of programme was to some extent responsible for the delay in landing the 1st Brigade already referred to.] of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, which had arrived with divisional headquarters in the transport Lutzow, and that Br.-General H. B. Walker, B.G.G.S. Anzac corps, would take command of the brigade vice Colonel F. E. Johnston on the sick list. General Bridges at once decided to throw these troops in on his left flank, with orders to reinforce the line on Baby 700 by way of Walker's Ridge. A start was made by the Auckland Battalion (Lieut.-Colonel A. Plugge) in this direction, but after proceeding some distance the rugged slopes of the ridge appeared so difficult and so exposed that General Walker-unaware of the existence of the Razor Edge-passed the word for the troops to retire, and to proceed to Russell's Top by way of Plugge's Plateau. The change of plan was unfortunate. Many of the men could not be recalled; the remainder, like the earlier arrivals, lost their way. Companies and platoons became scattered and intermixed. Some of the men found themselves on 400 Plateau; others on MacLaurin's Hill; others again at the head of Monash Gully; and not more than one company appears to have reached the Nek [ Lieut.-Colonel D. McB. Stewart, Canterbury Battalion, was killed in the fighting near the Nek during the afternoon, and Lieut.-Colonel Plugge was wounded.] before 1.30 pm

Thus it was that throughout the day the Anzac fortunes on Baby 700 were jeopardized and eventually ruined by the extraordinary difficulties of the ground. Thanks to the gallantry and devotion of officers and men, the Turks were kept at bay on that dangerous left flank, but the invading reinforcements were invariably so disorganized by the time they reached the Nek, that it was never possible to develop their full power. By 3 pm the Australians and New Zealanders on the spot consisted of fragments of no less than seven battalions, all very intermixed, and all more or less worn out by a succession of spasmodic and disjointed attacks. There was no one in chief command of this section of the battlefield; the scattered companies had no knowledge of what was required of them; and unity of effort was impossible. For several hours the line had swayed backwards and forwards over Baby 700, each reinforcing detachment in turn succeeding in making a little headway, only to be driven back by Turkish rifle fire when it showed above the crest. The Turkish fire had sensibly increased since the morning; losses amongst officers had been heavy; [I The extraordinary difficulty of maintaining direction and keeping touch with the flanks in this tortuous scrub-covered country was mainly responsible for the heavy losses amongst officers. All leaders had to expose themselves very considerably to get their bearings, and thus formed an easy and conspicuous target for Turkish snipers.] since 1 pm the troops had been subjected to considerable shelling from the direction of Chunuk Bair, to which there was no reply. To lie out in the thick scrub under this shrapnel fire, separated from and out of sight of their comrades, unsupported by friendly artillery, ignorant of the situation, and imagining that they were the sole survivors of their units, was a severe strain to young troops in their first day of battle. For many the breaking point had already been passed.

This was the situation when, about 4 o'clock, the long expected counter-attack developed on both sides of Baby 700. Shortly afterwards the hill was in the hands of the Turks, and the sorely tried Australians and New Zealanders were falling back, some to the beach, some to Pope's Hill and MacLaurin's Hill, where they formed the first garrison of Quinn's Post, and a few to a small trench at the southern end of the Nek. Except for these few men, commanded by a corporal, [Afterwards Lieut. H. V. Howe, 11th Battalion.] and for two companies of the 2nd Battalion under Lieut.-Colonel G. F. Braund at the head of Walker's Ridge, [a The last two companies of the 2nd Battalion, under Colonel Braund, landed about noon and were sent to the left flank. The 4th Battalion landed at I2.45 pm and was kept in divisional reserve till 5 pm.] a clear road now lay open to the Turks across the Nek to the heart of the Anzac position. But the Turks, too, were scattered and disorganized, and for some hours they made no further progress.

Even now it was not too late for the situation to be restored. "If reinforced," wrote Braund to his brigadier at 5 pm, "I can advance." But General Bridges had just sent his last reserve to the right; the remainder of the New Zealand Brigade, and the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade, had not yet landed. Until these could arrive not another man was available. [The Otago Battalion began to land about s P.M. and was told to dig in on Plugge's Plateau.]

Simultaneously with the attack on Baby 700, a small body of Turks advanced against the seaward end of Walker's Ridge. A success at this point might well have had disastrous consequences, but the position was securely held by Captain ACB Critchley-Salmonson, [An officer of the Royal Munster Fusiliers temporarily serving with the Canterbury Battalion.] with a mixed detachment of 33 men belonging to five different battalions. Recognizing the importance of this flank, Critchley-Salmonson impressed upon his men the necessity of holding it at all costs, and the position remained intact till reinforcements arrived.

At 6 p.m. the situation at the Nek was still obscure, but a dangerous gap was known to exist between Second Ridge and Braund's troops on Walker's Ridge. Colonel Sinclair-Maclagan, still apprehensive of the Turks appearing in rear of him at any moment, asked that the 4th Australian Brigade should be sent up to fill this gap as soon as it arrived. At this moment the 16th Battalion, under Lieut.-Colonel H. Pope, was just landing, and Pope was ordered to push on with all available men to the head of Monash Gully. Starting soon afterwards with two companies of his own battalion, one of the 15th, and two platoons of New Zealanders, Pope eventually occupied the wedge-shaped hill afterwards known by his name. But, as in the case of all other parties which had advanced up Monash Gully, the tail of the column got separated from the head, and was finally used to reinforce the garrisons of Steele's and Courtney's Posts. At nightfall there was still a gap between Pope and Braund, and between Pope's right and the troops on Second Ridge. [This latter gap, at the head of the eastern fork of Monash Gully, was never bridged throughout the campaign. It was eventually securely held by cross-fire from either flank, but the ground at the head of this fork, known as the " Chessboard ", remained in Turkish hands, and much of the gully was under constant observation by the enemy.]

The Turks were fortunately too weary to profit by these opportunities or even to discover them; and, though a small party succeeded in pushing forward to Russell's Top, they did little damage, and were successfully accounted for next morning. There was, however, to be no rest for anyone on those rugged hill-sides that night. Worn out with fatigue, scattered and disorganized, it was impossible for either side to make further progress. But the noise of battle continued; and with only the flash of their assailants' rifles to guide them, invaders and invaded alike kept up a continuous fire. [Many times during the confused fighting that day, and especially after dark, men fired on their own friends in front or on the flank; and the story spread that the Turks had shouted out " Don't shoot, we're Australians". But the many assertions that the Turks employed this ruse were in no single instance substantiated.]

On Second Ridge, and particularly on 400 Plateau, where portions of no less than ten out of the twelve battalions of the 1st Australian Division were now engaged, the battle raged all the afternoon with unabated fury. Having been definitely ordered to remain on the defensive, the Australians in that sector were somewhat better placed than those on the left flank to resist a counter-attack, and their position gave many advantages to the defence. On the other hand 400 Plateau was an easy target for the Turkish artillery. A mountain battery was brought into action against it about 11 am, and throughout the afternoon three Turkish batteries covered it with persistent and well directed bursts of shrapnel fire. For the Australians, whose trenches on the 25th provided practically no cover, [1 Most of the heavy entrenching tools brought ashore were left behind on the beach, and the light entrenching implement was of little use against the stubborn roots of the scrub.] and who for most of the day were without artillery support of any kind, this first experience of shrapnel was very trying. Nevertheless the advanced detachments on the eastern side of the plateau held their ground tenaciously, and kept up so steady a fire on the oncoming Turks that throughout the afternoon the enemy never once set foot on the plateau. The value of this plucky stand was enhanced by the fact that, in rear, where the 9th Battalion had made its costly advance in the morning, there was a wide gap in the Australian main line on the western edge of the plateau.

Colonel M'Cay, naturally anxious about this gap, repeatedly asked for reinforcements during the afternoon. But with the exception of the 4th Battalion, not another man would be available till the remainder of the New Zealand Brigade arrived in the evening, and General Bridges had determined to keep this battalion in hand to meet a sudden crisis. About 4.45 pm, however, M'Cay again called for help, urging that the whole safety of the position would be jeopardized if another battalion could not be sent him at once. In face of this opinion General Bridges decided that he could refuse M'Cay's request no longer, and the 4th Battalion was ordered to the right. Scarcely had it started when news was received that the Australians on the left flank were retiring across the Nek, and Colonel Braund sent in the message that if reinforced he could restore the situation. But there was no longer a man to send.

With the assistance of the 4th Battalion the gap on the right front was filled about 6 o'clock and M'Cay's line then consisted of a succession of irregular lengths of trench from the seaward end of Bolton's Ridge to a point on 400 Plateau north-east of M'Cay's Hill, a total frontage of rather less than 1,200 yards. As darkness fell the gallant but worn-out detachments who had so long withstood the Turkish attacks on the eastern slopes of the plateau at last fell back to the main line. The Turks at this stage were too disorganized to follow, and for the rest of the night the summit of the plateau was occupied only by the dead.

Further south, meanwhile, a small column of the 27th Regiment, detached earlier in the afternoon to make a flank attack on M'Cay's extreme right, debouched from the southern end of Gun Ridge about 3 o'clock. Half an hour later, having overwhelmed a heroic handful of the 6th Battalion occupying an advanced position on the eastern slopes of Pine Ridge, it continued its advance towards Bolton's. To avoid exposure to the fire of Admiral Thursby's ships, a halt was then made in a gully till after dark. Eventually, between 8 and 10 p.m., the advance was resumed, and an attack was launched on the trenches of the 4th and 8th Battalions. But it was only a half-hearted effort, and a gallant sally by men of the 8th Battalion sufficed to drive it back.

This was the enemy's last attempt to penetrate the Australian positions on the 25th April. But throughout the whole length of Second Ridge, as on the extreme left, there was to be no rest for the weary troops, and all through the night thousands of rounds of ammunition were expended in ceaseless firing. The absence of artillery support during the greater part of the day was a very severe handicap to the Australian and New Zealand troops, especially to those who were suffering from unanswered Turkish shrapnel. Before the landing it had been expected that two batteries of mountain guns would be ashore before 9 am and in action immediately afterwards, and that several batteries of field artillery would be landed before noon. It was also expected that the fleet would be able to render considerable assistance with its guns.

The following arrangements had been made for naval support:

i. The O.C. covering force to ask for ships' fire by signal, the objective to be indicated by reference to map squares.

ii. The fleet, on its own initiative, to open fire on any Turkish troops or guns clearly visible from the sea.

On each flank an artillery officer to act as an observer for the ships. Messages from these officers to be transmitted to the beach by telephone and thence by W/T to the flagship.

In the event, however, practically none of this support was forthcoming.

One mountain battery [The 26th Indian Mountain Battery commanded by Captain HA Kirby.] was ashore by 9 am, but it was long before any suitable position could be found for it, and, though it eventually came into action soon after midday on the western slopes of 400 Plateau, its position was quickly enfiladed by a Turkish battery on the main (Chunuk Bair) ridge, and at 2.30 pm, after sustaining heavy casualties, it had to withdraw. This battery, and one 18-pdr. gun which landed at 3.30 pm, were the only guns disembarked before 6 pm. To some extent this delay was due to the lighters being detained to evacuate wounded, and partly to disorganization caused by the shelling of the anchorage.

In addition to the two 2 2-cm. guns at Gaba Tepe, a Turkish battleship in the Narrows shelled the anchorage intermittently during the morning, and compelled the transports to move out to a safer position. At the time, those watching the landing were surprised that the Turkish battleship ceased firing just when her fire was causing most annoyance. From a neutral military attaché, however, who was present at Chanak on 25th April, it has been ascertained that this relief was directly due to the Australian submarine which passed up the Narrows on the 25th. The Turkish battleship caught sight of her periscope just above Chanak, and had to run for safety. Thus the Australian submarine was very appropriately of direct assistance to the Anzac landing.

General Godley had signalled to the flagship at 1.45 pm, begging that his howitzers might be sent in quickly, but was told that no lighters were available. Later in the afternoon, however, definite orders delayed the arrival of the guns. General Bridges had come to the conclusion that the ground was almost impracticable for field artillery, and that in any case the situation was still too critical to admit of guns being landed. He seems to have expressed this view to the corps commander, who visited his headquarters during the afternoon; for at 3.45 pm General Birdwood signalled to Admiral Thursby: "Please stop sending field artillery". The admiral thereupon ordered the transports to land no more guns, [ In one case Admiral Thursby's order miscarried, and two more field guns arrived at the beach late in the afternoon, but these were at once sent back to their transport. When the artillery officer, who had been reconnoitring for a position and who knew nothing about the order that had been issued, returned to the beach and found the guns gone he did his best to recall them, but found it impossible to get into touch with the ship.] and to re-embark any that had already been transferred to lighters, and thus it was that the troops were deprived that evening of the moral support of hearing their own artillery in action.

As for naval gun-fire, the ships were for most of the day compelled to remain idle. It was impossible for the warships, even with the help of balloon-ships and seaplanes, to pick out targets for themselves, nor could they search the approaches to the shore without knowing the whereabouts of the Australian line; and information on this point was particularly slow in reaching them. About 5 pm, however, the fleet was at last given an opportunity of assisting the troops. Since 12 noon an officer on Pine Ridge had been trying to send back a report describing the position of two Turkish guns near Anderson's Knoll, but all his messages miscarried, and it was not till 5 pm that the report at last got through. A quarter of an hour later, to the intense delight of the harassed troops, naval gun-fire opened accurately on Anderson's Knoll, and the guns which had so long tormented them were silenced.

The transports bearing the 4th Australian Brigade and the remainder of the New Zealand Brigade arrived off Anzac Cove about 5 pm, and it was then decided that General Godley's division should be allotted to the left flank. Some of the troops, including two companies of the Wellington Battalion (Lieut.-Colonel W. G. Malone) and the majority of the 16th Australian Battalion, were landed almost immediately. But the divisional Staffs were by this time considering the possibility of having to evacuate the whole position that night. Vague rumours to this effect spread along the shore, and the doubts and uncertainties raised by this possibility, coupled with some lack of organization on the beach, were responsible for further delays. A study of the war diaries of some of the battalions of the 4th Australian Brigade throws a vivid light on this subject. Thus the 13th Battalion arrived at its anchorage at 4.30 pm - Its disembarkation did not begin till 9.30 pm, and did not finish till 3.30 am on the 26th. The 14th anchored at 5 pm, but its landing was not begun till next day. Numbers of lighters, filled with wounded, arrived alongside the transport during the hours of waiting, and many of the men spent the whole night in carrying the wounded below. Equally trying to the troops concerned was the experience of the 15th Battalion. Anchoring at 4 pm, two companies of the battalion were crowded on board a destroyer half an hour later, but were not disembarked till 10.30. While awaiting disembarkation the destroyer came under shell fire, and some of the men were hit.

No story of the Anzac landing would be complete that did not mention the three field companies of the Australian Engineers. Some of the 1st Field Company, landing with the advanced echelon, for the moment forgot their allotted role. They dashed forward with the leading infantry to the top of Plugge's Plateau and it was some little time before they could be re-assembled on the beach. Later in the morning the engineers were divided into three parties, one to make roads, another to search for water, and the third to construct piers for landing stores. Paths to the top of Plugge's Plateau, and a track for 18-pdr. guns to the top of Queensland Point were constructed during the day; and communications up Shrapnel Gully were greatly improved. A water-tank boat, provided with eleven galvanized tanks and pumps, was towed ashore, and early in the evening there was enough water available to supply the whole force. On the right flank, too, a certain amount of water was found in Shrapnel Gully. Pumps and water troughs were erected there, and a fair amount of water was available from that source late in the afternoon. On the left flank no water could be found in the first instance, but water tins were landed and sent to the troops in the line. As regards piers, a barrel pier had arrived by noon and a pontoon equipment a little later; and despite the continuous shrapnel fire from Gaba Tepe, an excellent landing-stage was erected in Anzac Cove. This pier proved invaluable for evacuating the wounded, and 1,500 men were embarked from it before midnight on the 25th/26th.

The cessation of the enemy counter-attacks on the evening of the 25th April makes a convenient point at which to break the thread of the Anzac narrative, and to follow the fortunes of the landings further south. But, before doing this, it is of interest briefly to notice the general results of the Australians' and New Zealanders' first day of battle, and to study the situation, first as it must have appeared that evening to the commanders on the spot, and secondly as the information now available shows it to have been in reality.

The actual results of the day's fighting may be summarized briefly as follows: the initial landing in the early morning (the operation involving the greatest risk) had been accomplished with slight loss. Fifteen thousand men were ashore; [ By 6 pm, the force landed consisted of 3 Australian infantry brigades, half of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, one 18-pdr. gun, 2 mountain batteries, casualty clearing station, bearer subdivisions of three field ambulances, details of engineers and signallers - approximately 15,000 all ranks-and 42 mules.] a comparatively favourable beach had been secured; the troops were in occupation of a position which, except at one point, where a dangerous gap existed, was practicable for defence; and, finally, they had succeeded in beating off a series of counter-attacks. The casualties, which amounted to two thousand, were undeniably heavy; yet they were no larger than might have been suffered by the 3rd Infantry Brigade in the first hour had its landing been strenuously opposed.

Fresh troops would be arriving during the night, and by early morning the weak points in the line could be strongly reinforced.

On the other hand, to the commanders on the spot, there appeared to be many disturbing symptoms. The sanguine hopes of G.H.Q. had proved illusory, and it seemed clear that the higher Staffs had greatly underestimated the difficulties. Three Australian brigades and two battalions of New Zealanders, fighting with great gallantry throughout the day, had been unable to gain more than half the objectives which G.H.Q. had assigned to one infantry brigade as its initial operation. Owing to the fantastic configuration of the ground, and the extraordinarily thick scrub, every unit had become widely scattered from the start, and its normal organization broken. Every available man had been hurried into the battle, and, for the moment, there were no reserves. The Turks, on the other hand, were believed to have strong reinforcements in the immediate vicinity. So much small arms ammunition had been expended that its replacement was causing anxiety, and the difficulty of sending water to the troops on those precipitous hillsides presented a very anxious problem. The number of casualties could not yet be estimated, but was believed to be extremely heavy. Exaggerated reports as to the serious situation in front were arriving at the various headquarters; [At 5.20 P.M. M'Cay reported to Bridges that a considerable number of unwounded men were leaving the firing line. Australian Official Account, 1 p. 454.] and, most impressive feature of all, a disturbing number of leaderless men were filtering back to the beach. Though the officers who saw them did not realize it at the time, [The Australian Official Account, 1. p. 453 states: "Officers of the various headquarters, being mostly behind the lines, were also deeply impressed by the stragglers who, in ever-growing numbers, began to find their way back into the valleys behind the firing line."] hardly any of these men were stragglers in the ordinary sense of the word. Some of them had come back to the only centre of authority they knew in search of fresh orders. Others had returned in consequence of rumours that an order had been given to retire. Many of them, though desperately weary, were in high spirits, the reaction from the strain of the day. Elbowing and pushing their way about the crowded strip of beach, they were recounting their experiences, taking a "breather" after a hard day's work, searching for their packs (it was now turning cold), and sizing up the prospects of a meal. Hundreds of them were soon collected together, formed into companies, and pushed off to reinforce the left flank. But more and more kept drifting back to the beach. Few of them perhaps, had any idea that their return from the front might be misinterpreted, or was constituting an actual danger. But to the divisional Staffs in rear the scene on the beach was alarming.

Taking all these factors into consideration, the situation seemed gloomy indeed to General Bridges and his brigadiers; and the idea gradually began to take shape that in the event of a strong Turkish attack by fresh troops in the morning, the chances of preventing a disaster were remote.

At General Headquarters, though two telegrams despatched by General Birdwood had sounded a somewhat uncertain note, l the general tenor of the news had been encouraging, and not until midnight was the Commander-in-Chief to learn that the situation was considered grave.

The following messages were received from General Birdwood during the day:

"6.39 am. Australians reported capture of 400 Plateau and advancing, extending their right towards Gaba Tepe. Three Krupp guns captured. Disembarkation proceeding satisfactorily and 8,000 men landed."

"4.30 pm. Have now about 13,000 men ashore, but only one mountain battery. Troops have been fighting hard all over Sari Bair since morning, and have been shelled from positions we are unable to reach. Shall be landing field guns shortly and will try to solidify position on hill. Trying to make water arrangements."

"8.45 pm. Have visited Sari Bair position which I find not very satisfactory. Very difficult country and heavily entrenched. Australians pressed forward too far and had to retire. Bombarded for several hours by shrapnel and unable to reply. Casualties about 2,000. Hope to complete by night disembarkation of remaining infantry and howitzer battery. Enemy reported 9 battalions strong, with machine guns, and prepared for our landing."

In the peculiar circumstances of an opposed landing on a little known and mountainous coast it must always be more than usually difficult to pierce the fog of war. But, studied in the light of that knowledge which can only come after the event, the situation of the invaders at Anzac on the night of the 25th, so far from being unsatisfactory, would appear to have held many promises of success. Except at the head of Monash Gully, the position which the Australians and New Zealanders had occupied, and which at least 10,000 men were available to hold, was, despite many disadvantages, a strong one, and was only 6,000 yards long. With slight modifications it was destined to be the front line of the Anzac corps for more than three months, and, despite the yawning gaps between Russell's Top and Quinn's, all the efforts of the Turks in that period could never succeed in breaking it. The troops in front on the night of the 25th, though tired out with the immense strain of the day, were still in good heart. They knew that they held the measure of the Turks, and they asked only for reinforcements and artillery support to enable them to advance against the enemy next day. Most important of all, though this could not be known at the time, the Turks were more disorganized than the Australians, and they, too, had suffered 2,000 casualties, which was an even higher percentage of loss. From daybreak till 9.30 am not more than five hundred Turks had been actually engaged, and from 9.30 am till dusk a gradually increasing number which at no time exceeded six battalions.

At dusk on the 25th Mustafa Kemal was informed that the 2nd/57th Regiment had completely disappeared, that the Ist/57th was in dire straits, and that the commander of the 3rd/57th, which had been ordered to fill the gap between the two, had only some eighty to ninety men present. The 27th Regiment by the end of the day had suffered severe casualties, and was completely worn out. The condition of the 77th Regiment, composed of Arabs, was even worse. This regiment had been ordered to attack at dusk at the head of MacLaurin's Hill. After meeting the Australian rifle fire, it broke and fled in panic to Gun Ridge, whence some of the men fired all night into the backs of their comrades of the 27th and 57th. By daylight the regiment was completely scattered. The 72nd Regiment was the last regiment of the 19th Division to leave camp, and apparently did not reach the battlefield till the morning of the 26th. Like the 77th it was an Arab formation, and none too trustworthy. Yet it was the only reserve in Mustafa Kemal's hands.

It would appear indeed that by the evening of the 25th, despite the almost impossible task to which the mistake in the landing place had committed them, the Australian and New Zealand troops were within an ace of triumph. Yet such is War. The student of military history must ever remember that there is nothing more easy than wisdom after the event. To quote the words of Frederick the Great: "If we all knew before a battle as much as we know after its conclusion, every one of us would be a great general".

Seldom indeed has the mettle of inexperienced troops been subjected to a more severe test than was that of the citizen soldiers of Australia and New Zealand on their first day of active service. Hazardous as a landing on an unknown shore must always be, the task of the 3rd Australian Brigade was made still more arduous by the unfortunate chance which carried it to a landing place of unexpected and unexampled severity. The battle which then began cannot be judged by the standards of any ordinary attack, where the troops, carefully assembled beforehand, start from a definite line, at a definite zero hour. Arriving piecemeal in boats, landing under fire where best they could, wading ashore in the dark, finding themselves in many cases confronted by unclimbable cliffs, hunting for a practicable line of ascent, and then scrambling up a difficult hill-side covered with prickly scrub, it would have been hard indeed for units to avoid disintegration. The means of communicating orders and getting back information, always liable to interruption, were completely dislocated; the chain of command-none too strong at that time-was snapped. Individual groups of high-mettled men flung themselves forward on their own initiative; platoons and companies became fatally intermixed; and the plans for each battalion's special task fell hopelessly to bits.

Taking all these factors into consideration it may well be doubted whether even a division of veteran troops could have carried out a co-ordinated attack at Anzac on the 25th April. The predominant feeling, which that astounding battlefield must always arouse in the military student who visits it, will be a sense of unstinted admiration for those untried battalions who did so exceedingly well. The magnificent physique, the reckless daring, and the fine enthusiasm of the Dominion troops on their first day of trial went far to counteract anything they lacked in training and war experience. The story of their landing will remain for all time amongst the proudest traditions of the Australian and New Zealand Forces.

Further Reading:

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, Aspinall-Oglander's Account, Part 1

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, AIF, Roll of Honour

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, Aspinall-Oglander's Account, Part 2