Topic: BatzG - Anzac

The Battle of Anzac Cove

Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

Bean's Account, Part 2

The following is an extract from Bean, CEW, The Story of Anzac: the first phase, (11th edition, 1941), pp. 282 - 305.

CHAPTER XIII

BABY 700

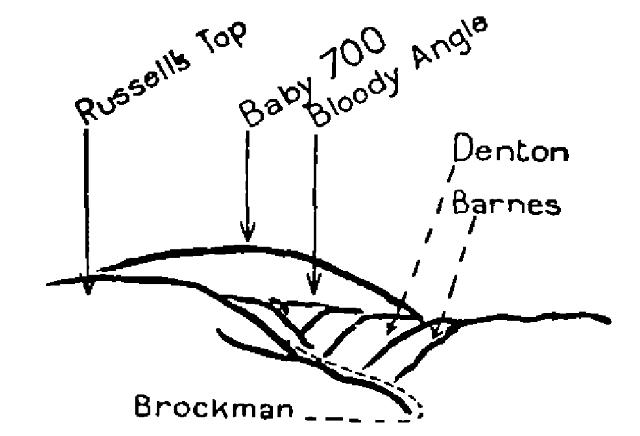

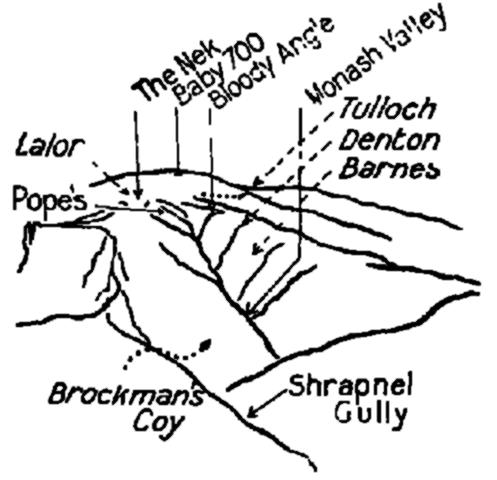

On being ordered by MacLagan to send detachments of the 11th Battalion to Baby 700 and the indentations which could be seen about the far northern end of Shrapnel Gully, Major Brockman told off companies or platoons to head for each of the points which MacLagan had indicated. He directed the two companies of the 11th under Captain Barnes and Major Denton to move along Shrapnel Gully to near its head and thence scramble up the scrub-covered indentations on its right (or inland) side. Brockman was under the impression that Hilmer Smith’s company of the 12th was proceeding to the head of the right-hand branch of the gully (afterwards known as the “Bloody Angle”).

Having thus provided for the right of the gully, he decided to take two companies, his own and Leane’s, to Baby 700. He meant to make his approach, as instructed, up the apparently continuous ridge from Russell’s Top. By this time, however, Major Roberts, second-in-command of the 11th Battalion, had arrived on the top of the plateau and had decided to keep Leane’s company there in reserve. Brockman left Plugge’s to join his company in Rest Gully below and lead it up to Baby 700. But, before doing so, he climbed across the valley on to Russell’s Top in order to see the country over which his company would have to advance. From the Top he saw - what it was impossible to realise from Plugge's Plateau or from the map (which was completely wrong in these details) - that an elbow of the left or main branch of Shrapnel Gully ate deeply into what had seemed to be the continuous ridge from Russell's Top to Baby 700. The ridge connecting the two heights was pinched between the western branch of that valley-head and a gully leading to the sea, thus forming The Nek near which Colonel Clarke had been killed. On the Top Brockman found Captain Lalor and his company of the 12th reorganising. Tulloch had already gone ahead, but with Lalor was Major S. B. Robertson of the 9th Battalion. Having arranged that Lalor should move up the high land to Baby 700 while he himself should follow Robertson up Brockman returned to his own company in Rest Gully.

Landing in the dark in scattered boatloads, and having to rush the steep broken hillside above the beach, all the companies had become somewhat mixed; but in many cases and at many times during that day they were faithfully reorganised - officers and non-commissioned officers carrying out in letter and in spirit the training of Mena Camp. Brockman's company had reorganised in Rest Gully; as part of this proceeding its second-in-command, Captain R. W. Everett, had been put in charge of a provisional company composed of men of all battalions. Everett had for one of his officers Lieutenant Selby, a Duntroon cadet, but most of his platoon commanders were non-commissioned officers told off on the spot to provisional platoons. Brockman sent Everett's company to the indentations near the head of Shrapnel Gully to assist Denton and Barnes, who had already been despatched thither. His own company he divided into two. Half of it, under Lieutenants Rockliff and Macfarlane, was to climb the right of Shrapnel Gully near to Denton and Barnes, and then to work round the edge of the valley to Baby 700. Lieutenant Morgan, with the other half, was to work up the valley to the head of its left fork, and thence on to Baby 700. Having sent away these detachments, Brockman signalled across Rest Gully to Plugge’s for another platoon. Captain Leane, who received the signal, sent him a platoon of his own company under Lieutenant Cooke. When it arrived, coming down the steep zigzag path past the three tents, Brockman went off with it up Shrapnel Gully towards Baby 700.

Just above the point where Rest Gully joins it, Shrapnel Gully takes a sharp bend to the left, thence running for half a mile straight to the north-east towards the fork in which it ends. When the features of the locality came to be named during the weeks following the landing, this upper portion of Shrapnel Gully was called, after the brigadier whose headquarters were situated in it, “Monash Valley.” Monash Valley lay between Russell’s Top on its left or western side, and the steep and much-indented ridge on the right, up which Denton’s, Barnes’s, and Everett’s companies had been directed. At the top of this straight half-mile is the fork before mentioned.

The branch to the left runs for another half-mile between steep sides, gradually becoming gentler till it ends in a spoon-shaped depression at The Nek. The branch to the right is shorter, narrower, and much steeper, and ends abruptly on a part of the inland slope of Baby 700, which came later to be known (from the trenches which afterwards gridironed it) as the “Chessboard.” The head of this branch is the “Bloody Angle.” Between the two branches lies a long razor-backed hill, fitting into the jaws of the valley as a stopper fits into a bottle.

This was subsequently named (after the colonel of the 16th Battalion, which reached it towards the end of the first day) “Pope’s Hill.” As each company of the 11th went off to its objective, it descended into Shrapnel Gully and made its way up the sandy creek-bed, which, with a thin trickle of water dribbling down it, formed the bottom of Monash Valley. Denton’s company held on, finally turning to its right just before reaching the foot of Pope’s Hill, and climbed the steep scrubby recess in the gully side which afterwards became known as “Courtney’s Post.” Barnes’s company turned up the recess immediately before it-a still steeper niche, of which the top was a sheer landslide of gravel where a man could scarcely climb on hands and knees. This was afterwards named “Steele’s Post.” Everett led his composite company up to the same recess as Denton.

The side of Monash Valley facing the enemy thus became at an early hour fringed with several strong posts. But the movement of troops up through the valley to Baby 700 was far more difficult. Companies or platoons, roughly organised, would move up the narrow stream-bed in single file, their officer leading. The officer may have been shown the spot to which they were being sent, but of the long string of men toiling behind few had any knowledge of a precise destination.

A couple of men, for example, were told by some officer to carry a box of ammunition and follow Lieutenant Morgan They plodded, perspiring, at the tail of Morgan’s platoon to a point near the valley head, where heavy shrapnel fire came sweeping upon the party. The pellets swished like hail through the bushes, and in the rushes from shelter to shelter the party became split. The men with the ammunition went up the slope to the left; Lieutenant Morgan and others led up the slope to the right. When once the string was broken, the men behind had no direction to follow. Each could only push on as he thought best, until some other officer or non-commissioned officer gave him other orders. Such was the fate that day of many similar parties. Moreover as troops moved up Monash Valley, those lining its top were periodically calling for reinforcements.

These orders were frequently given by senior officers in command on the valley side; and all day long troops who had been directed up the valley to Baby 700, tended, as they went, to be sucked into the fighting on the right-hand side of Monash Valley.

Of the troops originally directed to Baby 700. Leane’s company had been held back. Half of Brockman’s, under Lieutenants Rockliff and Macfarlane, after climbing, as instructed, a recess near Barnes’s and Denton’s companies, was a retained there to hold part of the edge of the valley. The other half, under Lieutenant Morgan, continued up the valley according to orders and made along its left branch towards Baby 700. Near the head of the valley it became split up by heavy shrapnel fire; part moved onto Russell’s Top on the left, while Morgan and others, following the directions, held on over the base of Pope’s Hill towards Baby 700. Close beside him went the platoon under Lieutenant Cooke, which Brockman accompanied.

Thus not all the troops directed from Plugge’s against Baby 700 were actually moving towards it. On the other hand there were already at The Nek or on Baby 700 fragments, mainly of the 12th and 11th under Lalor, Tulloch, and SB Robertson, which had gone there direct from the beach by climbing the heights near the Sphinx. Another small fragment of the 11th, under Lieutenants Jackson and Buttle of Tulloch’s company, after climbing near the Sphinx, had crossed Shrapnel Gully to some position ahead of Denton. Seeing other troops there pushed back, they retired, and met their own half-company commander, Captain Tulloch, near The Nek.

In the last chapter Captain Lalor, with his own company and several odd platoons of the 12th Battalion, was left on Russell’s Top, just where the ridge began to narrow to The Nek. Colonel Clarke was dead, Colonel Hawley and Major Elliott had been wounded, and Lalor was the senior officer with the party. The Turks whom Clarke’s men had chased from near the Sphinx had run off by the curving track over The Nek onto Baby 700, where they sank into the scrub.

Beyond The Nek, facing Lalor, rose the long back of Baby 700, a narrow ridge ascending gently for half a mile. The scrub on it was very open, part of the hill being almost bare. The retreating Turks had settled into the scrub slightly on the seaward slope, about 1,000 yards away.

Neither he nor Lalor had then any idea of what had happened to the rest of the landing force. Tulloch had tried to get into touch with Major Roberts, second-in-command of his battalion, but had failed. He knew that the 11th was to rendezvous on Battleship Hill - "Big 700" as it was then called. Big 700 and the further crests of the main ridge must be behind the long slope of Baby 700 which faced him. The orders were to push on at all costs. Tulloch had therefore decided to advance across The Nek to Big 700, where he might meet the rest of the 11th Battalion. Lalor, as has been said, remained digging a semicircular trench on the Australian side of The Nek.

The instincts of this fiery little officer were all for pushing ahead, and it was only his keen sense of the importance of the place, and the duty of the 12th as reserve battalion, that kept him there for a minute.

Tulloch decided to keep rather on the inland side of the crest of Baby 700. In order to make sure that Turks from the seaward side should not creep in behind him, he despatched Lieutenant Jackson with a party to that side of the hill to guard his left rear. At the same time, since the Turks were still firing across the head of Monash Valley, he sent forward a few men past the left of The Nek to work round and dislodge them. Presently the fire ceased, and Tulloch's party crossed The Nek.

Tulloch had about 60 men with him. They crossed The Nek in small groups, and having on the far side extended into line facing the direction in which Tulloch believed Big 700 to be (roughly north-east) , advanced through the scrub slightly inland of the crest of Baby 700. The slope was crossed by several undulations - depressions which ran down into the deep inland gullies to the right of the party as it advanced. If the men had looked over their right shoulders, they could from this the nearer hills, a triangle of shining water which was the goal of all this campaign - the Narrows.

But few of them noticed it. They were intent on the ridges ahead. The line advanced over the shoulder of Baby 700, across a depression, and onto the shoulder of the nest hill, still keeping a little on the inland side of the crest. The summit raised its head between them and the sea. Tulloch had with him Lieutenant EY Butler, of the 12th Battalion, who had been with him from the start, and also Lieutenants Mordaunt Reid and Buttle, who, with about thirty men, had been sent on across The Nek by Lalor.

The sun was bright, the sky clear. As the men pushed through the low scrub knee-deep, the fresh air of spring was full of the scent of wild thyme. On the dark, scrub-covered undulations about them there was no sign of life. The sound of firing came from the valleys on their right rear. Some bullets fired at long range lisped past them whenever they reached a crest or were on the downward slope. In the valleys not a shot came near them.

Tulloch’s line was advancing with about seven paces between the men. On the top of the second shoulder it was fired upon from a position half-way up the next rise. The Turks - of whom, judging by the fire, there were about sixty -were in the scrub some 400 yards away. From somewhere behind the enemy’s front a Turkish machine-gun opened, The Australians threw themselves down and began to fire. By this time about ten men in Tulloch’s party had been hit. His line lay in the scrub, keeping up a carefully controlled fire, as it had been taught to do in the Mena training. It beat down the Turkish fire: the shots from in front slackened; and the Turks melted. Tulloch’s line rose and advanced across the intervening dip and over the crest which the enemy had been defending.

To their left front there now rose another and still larger crest of the main ridge, its bare summit being about half a mile away. Between this and the shoulder on which Tulloch now was there lay a distinct depression. Bullets from somewhere on the opposite hillside began to “zipp” past the Australians, but the men could not see the Turks who were firing at them. The dark knuckles of the range, all covered with the same low scrub, sloped down to their right in longer and shorter ridges. Half-hidden by a knuckle ahead of them were three large sandpits, quarries, or landslides, which broke the dark flank of the hill.

The bullets chipped the hard leaves of the holly scrub and scattered them in fitful showers on the Australians lying below, the prickly fragments filtering under their tunic collars and down their backs. The men went forward for 150 or 200 yards by rushes, and then crawled another 100 yards on their bellies; raw soldiers as they were, they were making as good use of cover as the Turks. The Turkish fire grew heavier upon the place which they had just left. So long as they lay still, the fire was desultory; it was only when they made a rush, or began to scrape themselves cover with their entrenching tools, that they brought down a storm of bullets.

The sun was high in the sky, and it must have been after 9 o’clock when the line crept down the last hundred yards of its advance. The men were doing everything they had been taught. Orders were repeated along the line by word of mouth. The fire was not haphazard, but the men were shooting carefully at the targets pointed out to them from time to time by their officers. During a lull Tulloch passed along an inquiry as to how far water-bottles had been kept intact in accordance with orders, and he found that they were practically untouched.

The point which they had reached was almost certainly the south-eastern shoulder of Battleship Hill, a few hundred yards inland from its crest. The higher hill, of which the lower slopes faced them across the valley, was the shoulder of Chunuk Bair, a commanding height which, even more truly than Hill 971, was the key of the main ridge. On its skyline, which the men could see about 900 yards away on their left front as they lay in the scrub, was a solitary tree. By the tree stood a man, to and from whom went several messengers. Tulloch took him for the commander of a battalion and fired at him, but the flick of the bullets could not be seen in the scrub, and the officer did not move.

At this point the firing became very heavy.

The enemy had a machine-gun or guns firing at very long range. But few Turks could be seen ahead; they were lining the knuckle in front of the sandpits, 700 yards away: where the sharp edge of the ridge gave them perfect cover. To the south - on his right - Tulloch could see another line of the enemy lying down and firing at a line of Australians which was busily digging itself cover in a depression about half a mile in the right rear of his own party. These Turks were almost in continuation of his line, and were intent upon the Australians to their front, while Tulloch’s men were firing at them, from time to time, in direct enfilade.

The party fought here for about half an hour. Then bullets began to reach it from its left. This fire, at first at long range, became heavier and closer. Lieutenant Mordaunt Reid, who was carefully controlling the fire from the right of Tulloch’s line, was severely hit through the thigh. One of his men went to help him crawl to the rear, but Reid was never thereafter seen or heard of by his battalion. It will be remembered that Tulloch had sent Lieutenant Jackson with twenty men to guard the flank from which this enfilading fire came the seaward slope of Baby 700. Hearing the rattle of heavy fire in that direction, he assumed that this must be Jackson’s party, engaged with Turks in his left rear. He knew nothing of the bitter struggle which (as will presently be told) was in progress on the seaward slope of Baby 700.

But it was obvious that the enemy were penetrating behind his left flank, between him and the party which he imagined to be Jackson’s. An increasing fire at short range from the left showed that the Turks were collecting in the dead ground behind the crest of Battleship Hill and creeping round his flank. Tulloch’s own party could not deal with them, being pinned down by heavy fire from in front.

He accordingly gave the order to withdraw. His line was organised in four sections. Two sections held on and fired, while the alternate sections doubled back through the scrub to a position from which they could cover the retirement of the other two. Thus by stages his party withdrew to Baby 700. Here half the party was left under an officer with orders to delay the Turks, while Tulloch and the other half came back to the seaward slope of Baby 700 near where it narrowed to The Nek. By that time shrapnel, low and well burst, was sweeping like an intermittent hailstorm down the heads of the gullies which dipped steeply to the sea. Australians were clustering in the head of the gully which formed the seaward slope of The Nek (afterwards called “Malone’s Gully”), close under shelter of the next spur. On that spur could be seen Turks in numbers. On Baby 700 and on its seaward slope there had begun a struggle of whose intensity the advanced party had no conception.

When Tulloch had gone forward, the position at The Nek where Lalor was digging the horseshoe trench, was very quiet.

Except for bullets, which continually sang over at long range, and the rattle of heavy rifle fire on the ridges inland, nothing stirred. Major S. B. Robertson of the 9th Battalion came up and halted for a time. Lalor had agreed to hold The Nek and not proceed further. But this fresh clear morning was wearing on and nothing was heard of Tulloch, who had gone far forward to the right front. The slope of Baby 700 ahead, quite unoccupied, shut out Lalor’s view of the range which he knew was the objective. He was by nature the last officer in the force to sit still and do nothing in so critical a fight. The grandson of Peter Lalor, who led the only armed revolt that ever occurred in Australian history - the insurrection at the Eureka Stockade on the Victorian goldfields - and the son of a doctor, he enlisted as a boy in the British Navy; deserted from that service; joined the French Foreign Legion; fought through a South American revolution: and finally was appointed to the permanent forces in Australia. As an aide-de-camp in Western Australia he had more than one interesting meeting with naval officers, who little dreamed of his story. He carried with intense pride a family sword, from which he would not be parted. He had it with him - in spite of all regulations - on this morning at The Nek, its bright hilt wrapped in khaki cloth.

About 8.30 a.m. Robertson and Lalor ordered an advance up Baby 700. Lieutenant Margetts, with his platoon, worked his way up the middle of the ridge, making about the midpoint of the line. Where the Turkish line had been, several Turks were lying dead. Margetts moved straight over the summit of Baby 700 and some way down its further side. Far below on their left were the Gulf of Saros and the beach curving away past the crinkled foothills to Suvla Bay. Out on the blue water lay the battleship Majestic. Margetts looked at his watch. It was 9 o’clock.

In front of Margetts’s party, where it lay down in the low bushes, there rose, across a shallow depression, the rounded pate of the next summit - Battleship Hill. A sparse scrub grew from its stony surface. Around its western or seaward shoulder ran a- trench.

Behind the right shoulder of Battleship Hill, half-screened by its crest, could be seen two of the further summits of the range, from which long spurs ran down inland. It was towards the nearer of these spurs that Tulloch’s party was then working, out on the right front. But there was no sign of these men, and those on Baby 700 had no knowledge that they were there.

The line lay down in the scrub on the northern slope of Baby 700. The men did not dig, and the enemy could probably see little of them. But from the first moment bullets were coming fairly thickly from somewhere on the inland slopes to the right, clipping the leaves and twigs from the bushes.

Lalor himself, true to his decision, retained a party in a supporting position immediately in advance of The Nek. On the seaward slope the firing line was under Major SB Robertson of the 9th Battalion. From the outset the fighting on this slope was heavy. Baby 700 itself was free of Turks, but the scrub-covered spur which sloped from it towards the sea contained a Turkish trench, with two communication trenches running hack towards the valley behind the spur.

These trenches and the far edge of the spur were manned by the enemy, and there swept across them, backwards and forwards for hours, one of the most stubborn fights of the day.

Some time after the forward line in this advance had reached the summit of Baby 700 there came from its left - the seaward slope - a call for reinforcements. Margetts turned his field-glasses upon the trench which ran down the seaward shoulder of Battleship Hill. About 9.15 a.m. he began to notice Turks coming down this trench into the valley on his left front, where they became hidden from sight. He judged the range at 900 yards, and gave the order to his platoon: “Communication trench, on left slope of far hill … 900 yards ... three rounds ... fire!” The difficulty in controlling fire at this point was that the men, extended at several paces from each other in the thick low scrub, were out of sight, and the line easily lost touch. It was impossible to speak to more than a few on either side. When the fire grew heavy and each soldier was forced to keep low, a man could scarcely notice the movements of the one next to him, much less of those fifteen or twenty paces away. At the end of an hour Margetts could find very few of his own men. Therein lay one of the great difficulties of the day.

Turks were undoubtedly creeping over the shoulder of Battleship Hill by the communication trench, and down into the gully on the seaward face between Battleship Hill and Baby 700. Here they could collect in cover on their side of the spur. The Australians opposing them had similar cover in the head of Malone’s Gully. The intervening spur was curiously like a hand with four fingers. Where it left Baby 700, the steep scrub-covered slope, 300 yards wide from the northern fork of Malone’s Gully to the gully in which the Turks collected, resembled the back of a hand ; a quarter of a mile down towards the sea it suddenly ended in sheer precipices of worn gravel; from these there ran down seawards four bare razor-backed ridges, perhaps more comparable to the legs of a spider than strictly to fingers, and ending near the beach in greater and lesser knolls, all very steep.

The fingers of this spur were far too precipitous to allow of movement; the struggle was entirely on the upper part of the scrub-covered slope, where it joined Baby 700, and on the side of Baby 700 itself. The Australians - a mixture of 11th and 12th Battalions with some of the 9th - crossed the head of Malone’s Gully and the flank of Baby 700 above it, and rushed the Turkish trench on the scrubby spur beyond the gully.

Shortly after they reached it, a machine-gun was turned upon them from a position higher up Baby 700 and almost directly to their right, from which it played down the length of the trench. The party was thus driven out, and withdrew to the edge of Malone’s Gully for shelter.

The word went up the line: “The left are retiring.” It reached Margetts and his party on the summit. The Turks had manifestly been creeping down over Battleship Hill to the left.

Margetts and his men withdrew for about 150 yards down the back of Baby 700, and there pulled up. They could see the line on their left retiring. The crest and slopes of Baby 700 were again open to the enemy. Turks filtered back into the trenches on the scrubby spur: it was their movement round the seaward side of Battleship Hill which forced Tulloch to withdraw.

By this time the reinforcing detachments which had been sent by Brockman towards Baby 700 had arrived. Lalor was with the supporting line some distance behind Margetts on that hill. Brockman met Lalor there, and Lalor agreed to hold the hill and attempt no further forward movement.

Losses had been heavy, and the Australian line was pitiably thin. The Turks had followed its withdrawal, and were reaching Baby 700.

Fortunately the driving in of the line on Baby 700 had been observed from another part of the front. Between 9 and 10 o’clock Colonel MacLagan, returning from his visit to the 400 Plateau, had seen in the distance the retirement of the Australians and the pressure of the Turks. He had just given up hope of further advance from the 400 Plateau against the objective ridge. He now realised that the Australians would have all that they could do to hold a defensive position where they were. Baby 700, looking straight down the valley which the Australians were lining, was clearly the key of the position.

Having placed his headquarters at the southern end of Monash Valley on the high shoulder of MacLaurin’s Hill, he could see every movement of the line on Baby 700. From that hour onwards he endeavoured to send all reinforcements up to the struggle which he saw in progress there.

By the time MacLagan came to this decision, the 2nd Brigade and part of the 1st had already gone into the fighting on his other flank. Troops were being rushed into action as soon as they landed, and of the 1st Brigade there were still to come one company of the 1st Battalion, two of the 3rd, and the whole of the 2nd and 4th.

MacLagan now made urgent requests for reinforcements for his left, and was at once given the two remaining companies of the 3rd Battalion, sent off by Colonel Owen, who was at this time on Plugge’s. How they were drawn into the fight at the head of Monash Valley will be told in another chapter. On their way up Plugge’s these two companies became sandwiched into a long file of the 1st Battalion, which had shortly before landed from the Minnewaska. The last company of the 1st. under Major Swannell, delayed by dumping its packs on the way up the hill, followed after the 3rd Battalion. The second-in-command of the 1st Battalion, Major Kindon, was, according to practice, at the tail of its last company. As he was passing through the 3rd Battalion on Plugge’s, Colonel Owen told him that MacLagan was asking for reinforcements to be sent in the direction of Baby 700, and asked him to divert Swannell’s company thither.

Kindon accordingly led Swannell’s company of the 1st Battalion into Rest Gully and up Russell’s Top, so as to reach Baby 700 by the shortest route. Swannell had with him Lieutenants Shout and Street and Captain Jacobs. It was after 10 o’clock when this company moved up Russell’s Top. In the meantime MacLagan could see the remnant of Lalor’s line being driven back almost to The Nek. The untried signallers of the 1st Australian Division had, nearly two hours before, completed the laying of wires from the divisional headquarters to both the advanced brigades, and MacLagan telegraphed to Bridges that the far end of Russell’s Top was “seriously threatened.” At 10.15 MacLagan told Glasfurd that it was doubtful if he could hold on.

If the Turks had reached Russell’s Top, they would have been actually in rear of Denton and of the rest of MacLagan’s line in Monash Valley. Bridges therefore ordered MacLaurin, commanding the 1st Brigade - his sole reserve - to despatch two companies of the 2nd Battalion to the threatened point.

Major Scobie, second-in-command of the 2nd Battalion, was instructed to take Gordon’s and Richardson’s companies. Gordon led on immediately after Kindon.

It was nearly 11 when Kindon, with Swannell’s company of the 1st Battalion, wound over The Nek, and, at the foot of Baby 700, ran upon the remnants of Robertson’s and Lalor’s line, which had been driven in from the forward slopes of that hill. There were probably about seventy of the 3rd Brigade at this place, but only a handful of ten or twelve was visible from the point at which Kindon and Swannell joined them.

Swannell’s company at once deployed, and, together with the remnant of the 3rd Brigade, charged the Turks who were on the seaward slope in front of them. The Turks ran, one of them lumbering back over the shoulder of the hill with a machine-gun packed upon a mule. For the second time the line swept at the double over the summit of Baby 700, and Margetts reached the same point, on the same path, which he had been occupying before. On this line the men of the 1st Battalion began to dig as quickly as they could.

But on reaching the inland slope of the hill they came under heavy fire. The Turks had run off to a trench which showed as a brown line through the scrub ahead. Bullets whipped in among the Australians from the front and from the right flank. The only way to escape them was to lie still; and it was difficult, while so doing, to keep up an effective fire. On the right, where Swannell now was, the line looked into a gully beyond the Bloody Angle, and in this there were several Turkish tents and an abandoned bivouac. It was near this spot that some of Swannell’s men were under a Turkish fire to which it was difficult to reply. Swannell had felt sure that he would be killed, and had said so on the Minnewaska before he landed, for he realised that he would play this game as he had played Rugby football - with his whole heart. Now, while kneeling in order to show his men how to take better aim at a Turk, he was shot dead.

The two companies of the end Battalion, which followed immediately after Kindon and his portion of the 1st, moved partly through Monash Valley. Gordon led his company up the head of that valley on to The Nek. He took out his map, settled his position on it, and began to organise his troops for the advance. He was a fine, tall, square-shouldered man and without fear. He was speaking to his men, when he fell shot through the head. Most of his company attached itself to the left of Swannell’s when it doubled over Baby 700. During the whole afternoon it was involved in the heavy fighting near the position of Margetts on the crest.

Richardson’s company of the end got upon the seaward slope of Baby 700 - left flank of the line. On climbing from Monash Valley, Richardson had crossed Russell’s Top to its seaward side near The Nek. As the company emerged, it saw Kindon’s and Gordon’s men doubling up the Richardson long summit of Baby 700 to its right. At the same time about sixty Turks near the head of Malone’s Gully, on the seaward slope of Baby 700 and the scrubby spur beneath it, were apparently beginning to retire. Richardson gave his men the order to fix bayonets, and charged across the head of Malone’s Gully. The Turks appeared to hesitate as the line approached; when it was within eighty yards, they bolted. The Australians, flinging themselves down, shot a score of them before the rest disappeared into the further gully.

The line on the left of Baby 700, whenever it went forward, was exposed to the fire, not only of the Turks behind the nearer spurs, but of others who were now filtering back upon the lower ends of those spurs, not far above the beach. Officers and men lying in the scrub were caught, one after another, by the scattered bullets. Major SB Robertson, thrice wounded, raised himself to look forward and was shot. “Carry on, Rigby,” he said to a junior beside him, and died. Lieutenant WJ Rigby “carried on” till he too was killed. Under this fire the left tended to withdraw to Malone’s Gully, and the troops on Baby 700 fell back with it. Indeed, with the seaward slope open to the enemy, there was nothing else for them to do.

The strain on the men lying out upon the forward slope was becoming almost unbearable. Some of the original line which had charged so gaily with Margetts and Patterson and old Colonel Clarke in the morning, and had gone up the hill so light-heartedly when the day was young, were still there.

“Close shaves” were so numerous that men ceased to reckon them. Thus Private R. L. Donkin, of the 1st Battalion, had two bullets in his left leg; a third pierced the top of his hat and cut his hair; one ripped his left sleeve; three hit his ammunition pouches and exploded the bullets; another struck his entrenching tool. Most of the men of the 3rd Brigade who had fought there were dead or wounded. Yet Margetts and a few others hung on with these newer arrivals of the 1st Brigade. The blue sky and the bright sunlight on the sleeping hills, the fresh mountain air which they had drawn into their lungs after that first onrush, still surrounded them as with the evil treachery of a beautiful mirage. The sweet smell of the crushed thyme was never remembered in after days except with a shudder. As with most of the others, it was Margetts’s first experience of war. So far as he knew, there was no one supporting him. He could only see two of his own men, but he knew that he had about twenty, because he could pass the word along the line: to them. Major SB Robertson, of the 9th, was supposed to be on his left, but he was probably at this time dead. So far as Margetts knew, there was no one else; no one to assume authority; no one to inform him what had happened elsewhere.

As hours went by the lines were greatly thinned and the torture of the fire increased. Further to the left, near the summit of the hill, where Gordon’s company of the 2nd Battalion was mixed with remnants of the 11th and 12th, the line swept backwards and forwards over the summit of Baby 700 no less than five times. Each time, after holding for a while, it was driven back. Almost every officer was killed or wounded, but Margetts still remained.

On the right, down the inland slope of the hill where Kindon was engaged, the strain was becoming at least as great. The fire from the right continually increased. The line on Baby 700 was isolated, with both flanks in the air, and Turks were filtering in and accumulating somewhere on either side. Through this increasing torture Major Kindon lay in the line with his men, steadily puffing an old pipe. Beside him on his left a man of the 12th Battalion lay in the scrub firing. Presently a bullet zipped past from the right. The man’s head fell forward on his rifle-butt; his spinal column had been severed. From the direction of the shot Kindon knew that the Turks must have outflanked him on his right. By the strength of their determination, and by that alone, officers and men were clinging to Baby 700.

Reinforcements for Baby 700 were asked for again and again, and although similar demands were received from every other part of the line, and especially from the right, it was realised by divisional headquarters on the beach that the position on the left was critical. General Bridges had suspected this immediately on landing, when he noticed the storm of rifle bullets still sweeping down Shrapnel Gully at 8 o’clock. This suggested a doubt as to whether the Turks had not worked in from the north along the sea border behind his left flank. After a hurried visit to the right, he strode directly back, with Colonel White and Lieutenant Casey, his aide-de-camp, to the top of Ari Burnu knoll, from which he could survey the long sweep of the beach as far as Suvla and the seaward foothills. Brigadier-General HB Walker, Chief of General Birdwood’s Staff, was on Ari Burnu. From the parapet of the Turkish machine-gun position on the knoll they scanned the foothills to the north. Australians were moving on the beach north of Ari Burnu - the 3rd Field Ambulance was there at work. There was evidently no immediate danger in the foothills. The group of Staff Officers on Ari Burnu was probably seen by the Turks from some point near Baby 700, for bullets flicked the parapet close to Bridges. White suggested that his chief should move, but Bridges took no notice of the suggestion until it was further urged by Walker. He then moved to a safer position. Although there was no present pressure in the foothills, Bridges saw that troops would have to be sent to hold Walker’s Ridge later in the day. For the present he despatched two platoons of the 2nd Battalion to form an outpost along the beach.

MacLagan’s telegram that Russell’s Top was in danger, and his anxious requests that all reinforcements for the left should go to that point, showed Bridges where lay the threat to his left flank. But the 1st Australian Division had been almost entirely used up. The 1st Brigade, which was the sole divisional reserve, had only the 4th Battalion and two companies of the 2nd now left in it. Bridges would have used them if necessary, but only as a last resort.

As soon, however, as the position was made good, the New Zealand and Australian Division was expected to land. Walker represented General Birdwood on the beach, and he and Bridges had already decided that the N.Z. & A. Division could best be used on Bridges’ left, and had informed its Chief of Staff (Lieutenant-Colonel W. G. Braithwaite) to this effect, when, at 10.45, General Birdwood signalled from the Queen that he was continuing the landing by disembarking the New Zealanders.

It was then that General Walker obtained his dearest wish - a transfer from Staff work to a fighting command in the field. Colonel Johnston, the British officer commanding the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, had fallen ill. Birdwood signalled that the brigade was to come under Bridges’ orders on landing, and that Walker was to command it. Walker at once went off to the foot of the ridge, which from then onwards bore his name, in order to survey the country in which his troops were to be employed.

The first part of the Auckland Battalion had already landed at g a.m., immediately after the last of the Australian Division, and had at once been directed to reinforce the left of the Australians on Russell’s Top, where Walker’s Ridge ran into it near The Nek. The Waikato and Hauraki companies had been sent northward along the beach with orders to reach this position by climbing up Walker’s Ridge, and their leading men were already far up this steep spur. But Walker, on reaching the foot of that ridge, near the beach, and seeing how bare and razor-edged the spur was, became convinced that battalions which were sent up it would be split and disorganised. They could only climb its precipitous goat-tracks in single file, and therefore must enter the battle in driblets, whereas he desired that they should operate as whole units, well-organised. He, like others, inferred from the maps that there was a continuous broad ridge from Plugge’s to Baby 700. The Auckland Battalion was therefore recalled; and later, as battalion after battalion was sent to him at Walker’s Ridge, he ordered them back on their tracks, with instructions to climb the path, now prepared, to Plugge’s, and move to the left up this supposed hill-slope to Baby 700.

MacLagan, on the other hand, from his headquarters on the far side of Shrapnel Gully opposite to Plugge’s Plateau, could see exactly what happened on the narrow summit of Plugge’s whenever reinforcements filed over it. Again and again he saw how, meeting shrapnel and rifle-fire there, they tended to lead on into Shrapnel Gully. The file being broken, and junior officers and men not having instructions as to the position, they were too often sucked into other parts of the line than those to which they were directed. MacLagan, for exactly the same reason which actuated Walker - to prevent disorganisation in impossible country - advised that all reinforcements should avoid the precipitous climb over Plugge’s, and should come into Shrapnel Gully by a detour southwards along the beach. But Walker, far up at his own front near Walker’s Ridge, did not know this. Battalion after battalion of New Zealanders was turned back with orders to go in over Plugge’s. Some of the earliest of the New Zealand reinforcements were disorganised by the turning of Turkish fire upon Plugge’s; and all of them, attempting to follow their instructions, became split up in the tangle of Rest Gully and Monash Valley.

It was past noon when the Waikato Company of the Auckland Battalion, reaching the bottom of the zigzag path, found a string of Australian troops - the tail of the 2nd or 3rd Battalions - filing up the valley past them. The New Zealanders waited till it cleared their head, and then followed it round the valley bed. On reaching the turn into Monash Valley, they began to climb the hill in front of them towards the firing line. But they saw men waving to them from the top to go on up the gully. The figures on the hill-top were those of MacLagan and his staff. The New Zealanders turned and filed up to the head of Monash Valley and so to the just beyond The Nek. They re-formed in this depression, advanced, and, 200 yards further on, came upon Major Kindon.

When the New Zealanders arrived, Kindon seemed to have only four or five effective men left with him. The others who could be seen were dead or wounded. Not another man was visible on either flank. To the left was the summit of Baby 700. It seemed a long endless slope, always gradually rising with little tracks running through it. The New Zealanders asked who was on the left, and were told that part of the 2nd Australian Infantry Battalion was there. Far behind, in the right rear on the distant 400 Plateau, could be seen Australian infantry with a battery of Indian mountain guns.

The Waikato Company reinforced Kindon’s line, and lay facing Battleship Hill under the same unceasing fire. The line was still over the crest, out of sight of the sea. Before it were the further summits and inland slopes; the three sandpits on the lower slopes of Chunuk Bair could be discerned peeping over some of the further spurs. Through the scrub on the nearer side of the sandpits ran a streak of brown. It was a Turkish trench, and Turks could be seen in it.

The captain of the Waikato Company, after lying on the crest for half an hour, made his way back to Kindon on his right and advised him to retire and dig in by The Nek. But Kindon would not hear of leaving his wounded. Accordingly the line stayed on. As long as the troops were lying down, the fire was steady and sustained; whenever they got up to advance, it became intense.

This fire gradually increased. The Australians and New Zealanders, lying in the scrub, could not see the Turks reinforcing in front and to the right of them. But reinforcing they certainly were, and pushing in on Kindon’s right.

At some time between 2.30 and 4 pm. a Turkish battery suddenly opened from the direction of the further crests of the main ridge in front of Kindon’s line. First one gun opened, and then a series of four. The first shell went singing over towards the beach; then the gunners gradually shortened their range, till the salvoes fell upon the slope of Baby 700 near The Nek and upon the heads of the two valleys between which The Nek ran - Malone’s Gully on the side nearer the sea, and Monash Valley inland. Any movement on the forward slope of Raby 700 brought upon itself this shrapnel.

At the same time the fire upon Kindon’s line grew. “We were faced with a machine-gun on the flank,” he said afterwards “and with shrapnel in front and rifle fire. We were up against a trench and couldn’t shoot much. We could simply lie there, and they couldn’t come on while we were lying there.” The fire from Kindon’s right showed that the Turks were penetrating past it towards Monash Valley. The struggle which was occurring in the Australian centre, on the folds east of the Bloody Angle, will be told in detail later. But inasmuch as it vitally affected the position on Baby 700, reference must be made to it here.

The eastern rim of Monash Valley was well-fringed with troops. But there was never any continuous line from the eastern head of the valley (the Bloody Angle) to Baby 700.

A spur of that hill, known as the Chessboard, connected the two positions. But although parties under Captain Jacobs of the 1st Battalion, Lieutenant Campbell and Sergeant-Major Jones of the 2nd, and others moved over the Chessboard, it was not continuously held. There was no unbroken line of defence north of Captain Leer’s company of the 3rd Battalion, near the Bloody Angle, until the right of Kindon’s position was reached. A few isolated parties between the two had to bear, with Kindon and Leer, the full force of the Turkish counter-attack.

On Kindon’s right, helping to fill this gap, lay Lieutenant Baddeley of the Waikato Company, with his platoon. Baddeley was never seen or heard of again. Further down towards Leer was a party of Kindon’s own battalion under Captain Jacobs. Before Kindon had arrived at Baby 700, two small parties of the 1st Battalion which were with him, under Jacobs and Lieutenant Shout respectively, were despatched to the flanks. Kindon sent Shout to guard his left rear. Jacobs, with a fragment of the battalion, had branched through the right fork of Monash Valley, up the steep scrubby recess of the Bloody Angle, and out upon the Chessboard-the spur which ran down from the inland side of Baby 700, and against which this branch of the valley ended. Crossing that spur, he found himself looking down into a steep valley, about 100 yards across, which ran down to the right just over the crest from the Bloody Angle. In this gully were the tents and huts which had been seen by Swannell. Jacobs led his men through this and another minor gully and over the crest of the next spur (the upper shoulder of Mortar Ridge). Here they occupied a line some distance down the forward slope. Ahead of them, to their left front, were Australians. The latter were the line on Baby 700.

Jacobs was thus echeloned to the right rear of Kindon’s line, and, as long as he was there, its right flank was fairly safe. His party was firing at Turks on a spur 600 yards in front. To the right Mortar Ridge ran down to the flats at the upper end of what were afterwards known as “Mule” and “Legge” Valleys.

As the party lay in that position, Turks began to be noticed crossing these distant flats. Jacobs, like Leer and all other officers who saw it, prayed for a chance that a machine-gun might arrive to check this movement. But no machine-gun was near. Lower down the Turks were driving through to the ridges and gullies behind Jacobs’s party; there was an increase in the fire from the right; and at some time between 3 and 4 p.m. he, like Campbell of the and others, was driven in and was compelled to withdraw in the first instance to the shelter of the Bloody Angle and of the recesses on either side of it.

It was about 2.30 pm., when the Turks were beginning to press Jacobs and penetrate to his right, that Kindon noticed that two New Zealand machine-guns had come up about seventy yards in his rear. In order to escape the heavy enfilade fire from his right, he withdrew his men upon these This part of the line was now largely held by New Zealanders, of whom Major Grant: who was killed at this spot, was either then or shortly afterwards in command. Kindon handed over the line to them and went to report the position to MacLagan.

Further Reading:

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, AIF, Roll of Honour

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, Bean's Account, Part 2