Topic: BatzG - Anzac

The Battle of Anzac Cove

Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

Bean's Account, Part 3

The following is an extract from Bean, CEW, The Story of Anzac: the first phase, (11th edition, 1941), pp. 306 - 321.

CHAPTER XIV

THE LOSS OF BABY 700

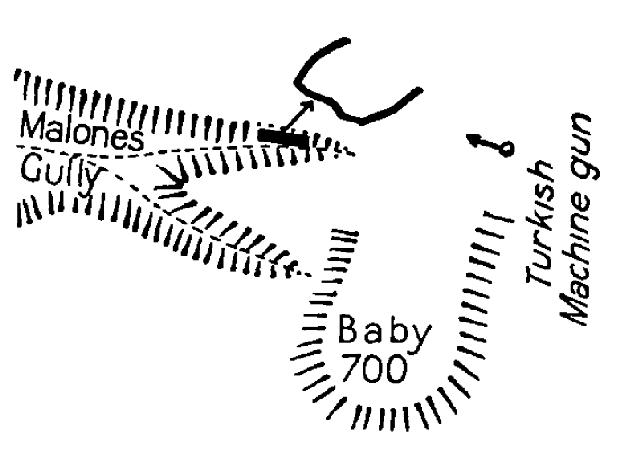

The line on Baby 700 was subjected to an even greater danger than that of being outflanked upon its right. There was the constant risk that, while it lay upon the inland slope of the hill, the enemy might creep round its left, along the seaward spurs which were hidden from it, and appear behind it.

When the Turks began to push past his right flank toward Monash Valley, Kindon had at least been aware of the fact.

But the seaward slope in his left rear was hidden from him by the crest of Baby 700; and all day long the men holding the inland slope of that hill could only trust that the parties which had undertaken to hold the seaward slope were doing their work.

It has been already mentioned that the officer who, through most of this endless day, had the responsibility of seeing that the Turks did not penetrate behind the left of the landing force was Captain Lalor. His duty was to hold The Nek and the seaward side of the hill while others fought inland. But while Kindon had been doggedly holding the inland slope, the fighting on the summit and seaward slope had continued extremely bitter and critical.

All that the men and even the officers knew was that the great effort of the expedition had been launched, and that it was their duty to see that it did not fail. The attack had manifestly not gone as was intended. The high hopes of the morning advance had long faded. They were up against the fire of some Turkish force, a comparatively scattered fire at first, but no\v incessant and always growing. Each man could only keep touch with one or two others on either side of him in the scrub, and, as one after another was hit, the line was thinned to breaking point. But they knew that all the other parts of the line must be depending upon them to hold the flank. If the line gave, it meant failure. With an unknown and increasing force ahead of them-with the long hours passing, and the enemy showing no signs of exhaustion-yet the determination of each individual man and officer still held them to that hill.

The ebb and flow of the struggle on the scrubby spur and the seaward Hank of the hill caused, as has been said, several retirements. But whenever reinforcements came up, the line would sweep again over the summit of Baby 700. On the occasion of the third retirement from the hilltop, Margetts had been told by some senior officer to line the edge of Russell’s Top in front of Walker’s Ridge, in case the Turks came round that way. But presently he was sent up to the front line again. He gathered all the men he could-about ten ii; all-and for the third time went up Baby 700. He found that a line had been re-established there and was being held by an officer of the 2nd Battalion and a few men. So far as Margetts and this officer knew, they were the only officers on the hill. The ammunition of the small party was running out. Margetts ran down the hill to find Lalor or the company sergeant-major or some other who could communicate with headquarters and obtain ammunition. At The Nek he came across a platoon. They were in the little horseshoe system of coffin-shaped rifle pits which Lalor’s men had begun to dig after the dawn. With them was Lieutenant Patterson, who had climbed near the Sphinx with Margetts. The Turks had just opened with their battery from the hills ahead, and were feeling for the range of The Nek. Patterson, being a Duntroon boy, was greatly interested in their practice Margetts found that Lieutenant Burt had gone back for ammunition and support. He himself returned to the line with this news. He was nearly exhausted; his clothes were still heavy with the morning’s soaking; again and again he stumbled and fell in the scrub. When he reached the line he found the officer of the 2nd Battalion and some of its men still there. His own men were gone. Margetts stumbled down the hill again to find them, and again reached Patterson.

The fire from the seaward spur of Baby 700 was now very severe, and shrapnel was increasing. Patterson and Margetts could see men moving on the seaward spur ahead of them, across Malone’s Gully, but were prevented from firing by a message which had just arrived from the left and had reached them by word of mouth shouted along the line.

“Don’t shoot if you see men on the left,” it said. “They’re Indians.” It seemed to them possible that this was true. An Indian brigade might be landing on the left, and the men on the spur seemed to be dark men. That message had strange results at a later time in other parts of the line. No Indians had landed or were landing on the left. The men whom they saw may have been Turks. though Australians were seen on the same slope afterwards.

The position on Baby 700 was obviously critical. Margetts had told Patterson that he was nearly “done up.’’ Patterson therefore went off with about thirty of his own men to reinforce the 2nd Battalion there. He made for a point on the seaward side to the left of where Margetts had been.

Margetts watched him cross the head of Malone’s Gully with his men.

In a support position on the seaward slope Margetts met Lalor. Lalor gave him a drink from his whiskey-flask-the drink of a lifetime-and let him lie down. Beside him was E. Y. Butler, who had been with Tulloch’s party, worn out and fast asleep. A moderate fire whipped over them, and the cry often went up for stretcher-bearers, but though bearers were at work further down the firing line, they had not reached this particular slope. Presently word came again that the line of the 2nd Battalion on the seaward slope needed reinforcements. Lalor turned to Margetts: I’ll go.

“You take your bugler and go down and see if you can bring some support and stretcher-bearers.” Patterson was never seen again.

“Take your men up,” he said - and then: “No.

“I’ll go forward, sir,” said Margetts.

“You’ll do as you’re told.” was the reply.

Lalor led his men off round the head of Malone’s Gully towards the scrub-covered spur, where the fight was thickening fast. Margetts descended the deep gutter of Malone’s Gully, putties trailing in the mud, to the flat far down at the bottom.

Here were some stray wounded from the fight above, and some stretcher-bearers. He sent the latter towards the crest, while he himself went to Major Glasfurd, at Divisional Headquarters on the beach, with the news that Lalor on the left was in urgent need of reinforcements. But by that time the need which was pressing upon headquarters was for reinforcements for the right. It was about 3.15 p.m. when Margetts left Lalor. Lalor had moved across Malone’s Gully onto the spur at the farther side. Here he took up a line under the fierce fire from the far edge of the spur and from the lower hills on the left.

He was presently joined by a party of the 2nd Battalion under Captain Morshead, who had kept further to the left than most of the platoons of the 2nd Battalion. The responsibility of that long day had rested as heavily upon Lalor as upon any officer in the force and, as the hours drew on, the difficulties were becoming heavier.

“It’s a __!” he said, as Morshead came up to him. “Will you come in on my left?” Lalor had by this time dropped his sword-hours later it was found back at The Nek by Lance-Corporal Harry Freame, of the 1st Battalion, who in his turn dropped it in the stress of the fighting at dusk. Lalor was excited and showing the strain. “The poor Colonel,” he said to Morshead. “He was killed - dropped just like that! I don’t know where Whitham is - hope he’s all right. He and I were pals…. Oh, it’s a __!” he reiterated.

Morshead made his platoon left form and move across to Lalor’s left. Lalor waved his hand, and moved his own line to join Morshead’s. Fire was coming from the lower knolls down by the beach. Lalor stood up to see, and resolved to charge forward.

“Now then, 12th Battalion,” he cried; and, as he said the words, a Turkish bullet killed him.

Most of the officers had fallen. The shrapnel fire on the head of Malone’s Gully and The Nek was exceedingly heavy.

The shells were burst well, ten or fifteen feet above the ground. The pellets swished through the low scrub and down the valley head like hail. At the head of Malone’s Gully one shell burst over Lieutenant G. W. Brown, of the 2nd Battalion, wounding six men, but leaving Brown unharmed.

Captain Tulloch, sheltering with some men under the edge of the same gully. had crept up onto the spur to reconnoitre, when he was wounded. Lieutenant Butler was wounded about the same time. Major Scobie, of the 2nd, walking along the line in the morning, had been hit on the bridge of the nose. Morgan of the 11th, Fogden of the 1st, and Richardson of the 2nd, had been wounded. Cooke of the 11th, Lalor and Patterson of the 12th. Gordon of the 2nd. S. B. Robertson of the 9th, Grant of the Canterburys, and many other officers, were dead.

On the left of the line there were now practically no officers surviving. A remnant of the 12th, on the seaward slope near the head of Malone’s Gully, was being led by a corporal, E. W. D. Laing. the senior among about sixty men of all units who were around him. Five times between 730 a.m. and 3 p.m. the line on this flank had charged over the 400 yards of scrubby slope in front of it, and each time it had been driven back. Towards the end it was difficult to prevent the exhausted nerve-racked men from retiring too far, but their leaders held them. In the last two advances there was only one officer within reach. When the fifth charge was made and the Turks withdrew into cover, Laing ran three times to this officer and begged to be allowed to take his men further and “get at the beggars with the bayonet.” He had just run across the third time and dropped beside the officer, when he was hit through the thigh. The word was given to retire, and the line withdrew. Laing crawled after it and reached shelter.

On the extreme left, sheltering in the head of Malone’s Gully were now about fifty men of all units without any officer at all. Possibly they came under Laing’s command, but they had been fighting mainly without leaders. In the scrubby slope, a short distance in front of the bank under which they lay, was the Turkish trench - the one with communication trenches running back from either end-which had been taken and lost earlier in the day.

At some time during the morning this party, without officers, had decided to rush the Turkish trench a second time. They waved to a few Australians, whom they could see firing from The Nek, to cross Malone's Gully and join them. This they did, mostly in search of their battalions. Here as elsewhere in this bewildering fight, most of the men, and many officers, supposed that the firing line of their battalion was somewhere ahead, and they had come forward looking for it.

Having thus added to its number, the party in Malone's Gully, by a sort of general consent, jumped over the edge of the gully, began to double across the spur, and ran suddenly into the trench. The Turks in it defended themselves. Some were shot, others bayoneted. Twelve lay dead in the trench.

The trench was almost straight, and no sooner had the Australians jumped into it, than a Turkish machine-gun somewhere on the slope of Baby 700 above to their right began to fire directly along it. The men took shelter by getting into the two communication trenches which ran from either end towards the gully beyond. From these trenches they could look out over the crest of the 0 spur towards the summit of Battleship Hill and the shoulder of Chunuk Bair. Part of the seaward slope between these heights was gentle, and across it, about 500 yards away, there were Turks advancing.

The position in the communication trenches seemed useless.

Australians had been there before, and their dead lay thickly in the scrub around. In order better to discuss what to do, the party withdrew to the head of Malone's Gully from which it started. It was decided to remain under the edge of the gully and wait for something to be done. On the far side of the gully Turkish shrapnel was raining, well burst and low, but the side against which the party lay was sheltered.

Later in the afternoon there came up the steep gutter of Malone's Gully from the sea a company of New Zealand infantry. It climbed to the men sheltering at the valley head, and its officer asked what the position was. Lance- Corporal Howe and others told him that the Turks were by this time back in their trench on the spur; that the trench was enfiladed and could not be held when taken; and that an advance would be useless. But from men under so great a strain such reasons for doing nothing could scarcely be trusted.

Like a brave man, the New Zealand officer decided that he must attack the trench again. He ordered the whole party to charge it.

When for the third time the trench was rushed, the Turks did not defend it, but ran back. The men who had been in the place before passed the word to get into the communication trenches and so avoid the machine-gun; those who knew made straight for these trenches. As the party reached the trench, the same machine-gun opened from the right. The first to fall was the New Zealand officer. The gun killed or wounded most of the men in the straight trench. Those in the communication trenches held on until the gust of rifle fire which the charge had aroused should subside.

This time, waiting in the communication trenches, the survivors perceived that there were Turks advancing not only over the seaward slopes of Battleship Hill, where they had seen them before, but also from the depression between Battleship Hill and Baby 700. This betokened no mere filtering back of isolated groups, but an attack on some considerable scale. The Australians and New Zealanders began to lose heavily under their rifle fire, and, with an attack of this character advancing, there was no small chance of their being cut off. Before, when they had sheltered in Malone’s Gully, a few wounded Australians had come in to them from some party out in the direction of Baby 700 on their right front; but the only Australians they now saw were in a line which they noticed to their right rear where the hill narrowed towards The Nek. They decided to join these.

As a matter of fact, shortly after Major Kindon had handed over the control of his line on the inland slope of Baby 700 to the New Zealanders, and after Lalor had made his last gallant advance and had fallen, a further reinforcement of New Zealand infantry had arrived. This consisted of a company of the Canterbury Battalion under Lieutenant- Colonel Stewart. After the two companies of Auckland (Waikato and Hauraki) had moved up Monash Valley. the two of Canterbury then ashore had climbed over Plugge’s and one, Major Grant’s, had gone on to Russell’s Top near The Nek. Lieutenant Morshead, of the 2nd Battalion, still holding on to the position where Lalor had been killed, received a message from his rear to say that a line of New Zealanders had been established there. Colonel Stewart seems to have placed his men at about 4 p.m. on a line across Russell’s Top a little short of The Nek. On his left front, beyond Malone’s Gully, there were the remnants of Morshead’s and Lalor’s men. On the summit and seaward slope of Baby 700 were still a few of the 2nd Battalion and 3rd Brigade. On its inland slope, on Stewart’s right front, was the remainder of Kindon’s line, composed of Aucklanders and of remnants mainly of the 1st, 2nd, 11th, and 12th Battalions.

Stewart evidently saw the line of Morshead’s men near Malone’s Gully. for Morshead received from him three messages at short intervals. The first was an order to retire upon the Canterbury line; the next-“Stay where you are.

We will come up to you.” A little later came a message to retire. In the interval between the last two the shrapnel fire upon The Nek had been tremendously heavy. A few minutes later Stewart was killed.

All parts of the Australian and New Zealand line on the left realised that a heavy attack was at this moment coming down upon Baby 700 and the slopes round it. Turks were moving in rough formations of attack from the direction of the main ridge. Even on the 400 Plateau, a mile to the south, where another heavy struggle was in progress, some found time to notice the great numbers of troops who came in company column to the main ridge, deployed into line as they topped the summit, disappeared for a time behind Baby 700, and then at about 4 p.m. attacked. The attack advanced across the slope and spurs of the range both on the seaward and inland side.

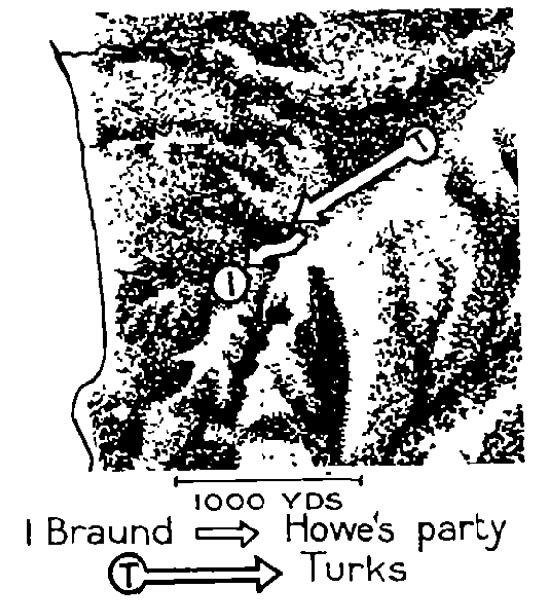

The only thing which could have saved Baby 700 was the support of guns and fresh troops. But, except for the 4th Battalion, which Bridges was keeping for use in the last resort and which he presently had to throw in on the right, the last reserve had been used. Colonel Braund, with the two remaining companies of the 2nd Battalion, had been despatched at about 1.30 p.m. with orders to reach the top of Walker’s Ridge by working up from the beach. MacLaurin, his brigadier, had reconnoitred the route and decided to send him that way and not by Plugge’s. Braund climbed up the steep goat-tracks under a harassing fire, and about 4 p.m. reached the junction of Walker’s Ridge with Russell’s Top. He pushed a short distance into the scrub, and lay where his orders directed. Not far to his right front must have been Colonel Stewart and his two companies of the Canterbury Battalion.

There were no other troops to send. The transports of the N.Z. and A. Division had not yet come up. The New Zealanders who had so far been landed were those from General Godley’s transport, the Lutzow, which arrived about dawn. The rest of the division-half of the Canterbury Battalion. the Wellington and Otago Battalions, and the whole of the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade-was still in its ships.

The transports of the New Zealand infantry were due to arrive at midday, but were not brought to their anchorage until late in the afternoon. The 4th Australian Brigade was not due to reach the anchorage until the evening. During the hours of the afternoon lighters and steamboats were used in clearing from the shore to the transports the great accumulation of wounded. From 12.30 to about 4 p.m. not an infantryman arrived on the beach.

Nor was any additional artillery brought into action during these hours. The 2Ist (Kohat) Mountain Battery, which should have landed at 8.30 am, waited in its transport through the long day for lighters to arrive and land its guns But till 3 p.m. none came, and no steam tug till 5.30 p.m.

No position for field-guns could at first be found in this precipitous country, and when two guns of the 4th Australian Battery were eventually brought to the beach, they were temporarily ordered away again. The naval artillery, being of little use against such targets as that day offered, could not support the troops, and almost ceased to fire. The battery of Indian mountain guns, which had been landed early and at whose mere sound the spirits of the tired men began to rise, had been driven out of action by a hail of shellfire. The bark of the supporting artillery had ceased. The enemy’s salvoes alone could now be heard. Such were the conditions under which Baby 700 and its flanks were held by a worn remnant of the landing force when the Turks swarmed down to the attack.

It was about 4.30 p.m. when the brave line which had held Baby 700 through the long day finally broke. Lieutenants Shout of the 1st and Morshead of the 2nd Battalion were two of the few officers still surviving on the seaward side.

On the centre and inland slope Aucklanders, with a few of Major Grant’s Canterburys and stray Australians, were lying in a scattered line about a hundred yards behind the front line. which still consisted mainly of Australian remnants.

Suddenly the front line came running back on them.

“The Turks are coming on thousands of them!” The Aucklanders rose with them, and the whole line trekked back down the hill which it had fought all day to keep. The slopes of Baby 700 were left bare. The remnants from Malone’s Gully were some of the last to retire. The Turks were very close upon this party, and it could hear them shouting on the other side of the spur. Its leaders, now two corporals-Howe of the 11th and a New Zealander - waited to see who were the men to whom these voices belonged.

Presently several figures came over the skyline 150 yards away. One of them, a Turkish officer, stood out at full height and looked through his glasses. Howe rested his rifle on a bush, took steady aim, and shot him. Then the two, having lost their party, ran across the narrow head of Malone’s Gully, looking for the line of men whom they had seen near the foot of Baby 700.

The slope was empty. The line had gone. Fragments of it, and of the other troops on Baby 700, had drawn back to each branch of Monash Valley. At this moment they were lining its edges at Pope’s Hill on the western branch, and at the Bloody Angle and the next recess south of it on the eastern branch. A few from Baby 700 wandered down a valley leading southward, which they thought they had passed that morning. Bugler Ashton, of the 11th, was one of these.

He had been in the act of bandaging a New Zealander on Baby 700, when the man was hit again and terribly wounded.

He cried to Ashton to kill him. Ashton rose to go for a stretcher, and then realised that the line had retired without his remarking it; he was alone. Making for a gully which he thought was Monash Valley, he found there a wounded mail of the 1st Brigade, whom he helped till the man could go no further.

Then Ashton went on. The valley was in reality Mule Valley, at the head of which Jacobs of the 1st and Leer of the 3rd had been fighting.

It opened into a green flat. As Ashton was crossing this, he heard a shout, and found himself covered by the rifles of ten Turks. Major Scobie of the 2nd, when wounded in the fight on Baby 700, wandered down the same valley. Although it was by then behind the Turkish front, he somehow reached the Australian line. But Ashton was seen by the Turks, who hit him on the head with a rifle-butt and captured him. Beyond doubt a few other Australians lost themselves in the same way, and in some places many of the wounded had to be left behind. Except for two officers and a private, who later mistook the Turks for Indians and were captured, Ashton was the only Australian who survived this battle after being in the hands of the Turks. Other fragments from Baby 700, that with Morshead for example, withdrew down some gully or other to the beach; others retired onto the upper end of Walker’s Ridge.

It will be remembered that Kindon had placed Lieutenant Shout to watch the slopes in his left rear. Shout had with him Lance-Corporal Harry Freame, a skilled scout, half Japanese by birth, who had fought in the Mexican Wars.

Shout had placed Freame by The Nek with fourteen men to hold it at all costs. Freame numbered his party off at intervals.

At the second numbering there were nine. At the last only one replied. Shout had been with Lalor and held on till the line retired. Then, taking Freame with him as he passed, he withdrew towards the beach.

Probably the last party to leave Baby 700 was that of Howe and the New Zealand corporal from Malone’s Gully.

When they found that the line was gone, they made across The Nek. Their party had been scattered and had suffered heavily; only five were together. As they passed over The Nek they stumbled, before seeing them, into two or three shallow scratched rifle pits with three machine-guns set up in them. These were two guns of the Auckland Battalion and one of the Canterburys, in shallow shelters within a distance of ten yards from one another-part of a semicircular system of rifle pits which crossed The Nek and overlooked the gullies on either side. This was the line which Lalor had been digging in the early morning.

A voice in the scrub cried “Snowy Howe!” It came from a man named Ferguson, of the 11th, who had been with the party in Malone’s Gully and had been heavily hit as he crossed The Nek.

No officer was there; the New Zealanders were under a sergeant. But it was a good position. They had sixteen belts of ammunition for the machine-guns and plenty for the rifles.

The crews of the machine-guns had all been killed or wounded, and the sergeant wanted men who knew how to work them.

Howe’s party stayed with the New Zealanders, and helped them to dig in as the evening closed. There were about fifty stragglers of all battalions in this last party on The Nek.

Solitary men who had been left on Baby 700 still occasionally strayed back to them. But the Turks in front had machineguns, and were sniping fairly heavily from tile trench on the spur beyond Malone’s Gully.

Those same Turkish machine-guns were noticed by Colonel Braund, whose two companies of the 2nd Battalion, unknown to the party on The Nek. were lying out in the scrub some way to their left rear near the head of Walker’s Ridge.

Braund knew that there were troops ahead of his line, and he held on blindly in the scrub against a heavy fire mainly in order to protect them. Lieutenant Shout of the 1st, on his retirement across The Nek, found Braund near the top of Walker’s, and at 5 p.m. Braund sent him to the beach with a message for MacLaurin: “Am holding rear left flank.

Against us are two concealed machine-guns-cannot locate them. In our front are New Zealand troops (and) portions of 3rd Battalion (probably he meant Brigade). Have held position (in order to) prevent machine-guns swinging upon troops in front. If reinforced can advance.” Urgent messages reaching Bridges about the same hour told him that the position on the left was critical: “Heavily attacked on left” - from MacLagan at 5.37; “3rd Brigade being driven back” - from the 3rd Battalion at 6.1 5; “4th Brigade urgently required” - from MacLagan at 7.15. Shout was sent back to Braund with 200 stray men of all battalions who had been collected on the beach, and, as the New Zealanders and 4th Brigade were now landing, the divisional staff sent Braund a message by Shout that he would be reinforced by two battalions, so that he might dig in where he was that night.

But the small party on The Nek itself was never reinforced. Dusk fell at about 7 o’clock. The New Zealand sergeant commanding the party had been wounded, and limped back with a message for reinforcements. Howe and the New Zealand corporal were now in charge of the trench.

Howe, with a stretcher-bearer, went back for reinforcements along the white track down Russell’s Top, and presently came upon a party of New Zealanders in a trench which had been partly finished across the track. They were probably what remained of Colonel Stewart’s companies, but a sergeant major now commanded them. Howe brought some of them back, with their picks and shovels, to the horseshoe trench at The Nek.

By dark the horseshoe trench was about two feet deep.

There had been a steady run of casualties in it all the afternoon.

As the dusk fell and the trench deepened the party began to feel comfortable. They knew of no one on their left, but at least in Monash Valley there were Australians, and what remained of Stewart’s line was close behind them.

As darkness fell, the Turks crossed The Nek and also the head of Malone’s Gully and attempted to occupy Russell’s Top. The men in the horseshoe trench could hear them, long before they came, shouting “Allah! Mohammed!” They let them come close, and then opened fire and drove them back.

This sort of fighting was easy after the strain of the day.

The moment darkness fell, the Turkish fire because inaccurate, and though plenty of bullets flew past, few men were hit. They drove the enemy back and went on digging.

The whole party signed a note asking for reinforcements and sent it to the rear. They said that the bearer of the note would guide the reinforcements up. No one, so far as they knew, was near them except the line of New Zealanders close behind. A note came back to them: “Hang on at all costs,” it said. “Reinforcements are on their way.”

But the reinforcements never arrived. At 8 p.m. a New Zealander who had been to the rear returned to the trench.

“Hey, Corp!” he said, “That mob behind us has gone.” Howe and the New Zealand corporal went back and found that it was so. Someone had come up and ordered the supporting line back. The trench was empty. But on either side of them - on the side of Monash Valley and in the scrubby slope towards the beach-they could hear voices.

At first they thought these were Australians, until a clamour of “Allah! Mohammed!” began. These Turks were well behind the horseshoe trench. Some of them came at it, and were shot at close range.

The party in the horseshoe trench, after holding a discussion, decided that the only course was to retire and get in touch with their own side. Some of the men knew that the white track along the Top led to the heart of the Australian position. They had no fear; they knew where they were, and how to get touch.

They picked up the three machine-guns, the belts of ammunition. and a dozen badly wounded men. One man would not allow them to lift him. He and three others were too badly wounded to be moved. As no one knew how to dismantle the machine-guns, they picked them up, tripods and all, as they stood, and retired along the path. When they had gone 200 yards, the Turks, who perceived the retirement, caught them up and attacked. It was an anxious moment.

The party set down its machine-guns and opened fire with them. Then it retired again. Near the Sphinx it tumbled over the trench which Clarke’s party had first charged that morning. Near by still lay the pack which Laing had carried for the old Colonel. The party held on down the white path and presently reached an old Turkish communication trench running into the top of Rest Gully.

Here they stopped. Rest Gully and Plugge’s Plateau were in sight of them. They knew where they were. The Turks followed them up and tried to dig in about 150 yards in front of them. The party on the edge of Rest Gully opened a heavy fire. The Turks replied, and the fire was kept up all night.

Small parties of Turks had thus penetrated far into the Australian position on Russell’s Top-but only on its inland side. Colonel Braund, with half the 2nd Battalion and New Zealanders, lay out in the scrub at the top of Walker’s Ridge; and, on the inland side, the fork of Monash Valley and a small length of each of its branches were held by remnants of the men who had been fighting all day on Baby 700. A few men of the 1st and 3rd Brigades lined Pope’s Hill and Dead Man’s Ridge. Captain Jacobs and some of his men, who from supporting Kin don’s right had fallen back on the Bloody Angle, now joined them. The Bloody Angle never at any time afforded cover against an enemy who held the Nek. Its rear lay completely open in that direction. About dusk Jacobs had ordered his party, worn-out with the interminable strain, to withdraw further down the gully. As it began to drop down the slope, a figure appeared on the skyline behind. “Set of cowardly bastards,” it said.

‘I never thought Australians were such a lot of curs!” It was a youngster of the 3rd Battalion. He was sobbing, half-crying with rage.

“What’s the matter, son?” asked Jacobs.

“My officer’s out there wounded, and you are leaving him,” he said.

Jacobs with several men went out where the youngster led them, and found an officer badly wounded. The boy had been carrying him over his shoulder. They brought him in.

Jacobs’s party, as has been mentioned, withdrew from the Bloody Angle to a recess on the opposite side of the gully. This indentation, which lay in front of Pope’s Hill, was steep at its foot, but a climb up the dry bed of a cataract - which gave it the name of Waterfall Gully - led to a shallow spoon-shaped depression at its upper end. Jacobs’s party lined the forward shoulder above this valley, between it and the Bloody Angle (later, “Dead Man’s Ridge”). There they lay, at dusk, facing the Chessboard, with Pope’s Hill just behind them. Others who had retired towards the Bloody Angle found their way into the next recess south of it. This indentation, although it was on the same side of Monash Valley as the Bloody Angle and had its back turned almost directly towards The Nek, was nevertheless partly protected by the shoulder which formed its extreme left. The 3rd Battalion had used the place as a track for men and ammunition to reach the fighting on Mortar Ridge. Here, in the afternoon, as the fight ebbed, fragments of the troops had eddied-Aucklanders, who were the last to move through Monash Valley, and stray men from the front made it their stopping place. At nightfall there remained in the green arbutus scrub on top of the recess 150 Australians and New Zealanders under Major Dawson of the Auckland Battalion. Probably a few men also stayed in the Bloody Angle till next morning, when, with the Turks directly behind them, they were either killed or driven out.

But the post in the southern recess of the two was not withdrawn. From that day until the evacuation, with its rear open to The Nek and its flank completely in the air, it remained, the most critical position in Gallipoli. The Australians and New Zealanders under Dawson who, with a New Zealand machine-gun which came up during the night, held the green scrub on its lip became the original garrison of Quinn’s Post.

Further Reading:

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915

The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, AIF, Roll of Honour

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Battle of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 25 April 1915, Bean's Account, Part 3