The following is an extract is an excellent summary detailing the history of the Australian light horse movement. It comes from Dennis, P., et al, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, 2nd Ed, OUP 2008, pp. 223 - 232.

The commitment of troops from Australia and New Zealand to the Gallipoli Peninsular arose out of the deliberations of the War Council in London and the desire of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, to seek a more offensive role for the RN. The War Council was a committee of the British Cabinet, formed to advise the Prime Minister (Herbert Asquith) on matters concerning the War. It consisted of Asquith himself, Field Marsha Lord Kitchener (Secretary of State for War), Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty), David Lloyd George (Chancellor of the Exchequer), Sir Edward Grey (Foreign Secretary), Arthur Balfour (former Conservative prime minister) and a floating group of other ministers and service advisers.

In December 1914 various members of this body had expressed concern about the lack of progress of military operations against the Germans on the Western Front. The French counter-attack after the Marne had stalled; Britain's original six divisions had suffered heavy casualties around Ypres; trench lines had now been dug from the channel to the Swiss border; and no Allied military figure seemed to have a clear plan of how the war was to be won. Into this strategic vacuum stepped the politicians. Lloyd George suggested that Germany could best be defeated by attacks on her weaker allies-Austria-Hungary and Turkey. Maurice Hankey, who was a Royal Marines Colonel and Secretary of the War Council, also suggested an attack upon Turkey in combination with such Balkan states as could be rallied to the Allied cause.

The most prolific source of ideas was Churchill. Since the outbreak of war he had been dissatisfied with what he determined to be the passive role played by the RN. Even before the Western Front had solidified he had put forward schemes to capture an island off the German coast, thus forcing the German Fleet to sally forth to retake it. The consequent great naval battle would see the Germans crushed, and the British Fleet enter the Baltic where in combination with Russian forces it would dominate the north German coast and force the German High Command to divert troops from the Western Front. That scheme had met with stiff resistance from Churchill's naval advisers. It would risk the Grand Fleet in shallow waters dominated by mines and submarines; the Germans might not come out and get sunk; and Russia had no troops to spare nor the expertise to carry out combined operations against the German north coast. Churchill then suggested using the Navy to blockade Holland into the war, or using the firepower of the battleships to assist the British and French armies with operations along the Belgian coast.

He also suggested using some of the older battleships to attack Turkey on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The first two schemes soon collapsed for much the same reason as the German island scheme they risked the Grand Fleet in mine and submarine dominated waters. The Gallipoli scheme, however, received some impetus from an outside source. On 2 January the Russians asked the British to mount a diversionary operation against the Turks who were pressing them hard in the Caucasus. Churchill seized on this message to ask the Commander of the British squadron in the Aegean, Admiral Carden, if the Dardanelles could be forced and Constantinople dominated by ships alone.

Churchill later stated in his memoirs that he detected a remarkable convergence of opinion at this time in favour of operations against Turkey. Lloyd George, Hankey, the Russians, Kitchener (who had passed on the Russian request to Churchill) and himself, he wrote, all favoured such action.

In fact there was no such major convergence. The scheme put forward by Lloyd George was mainly concerned with operations against Austria-Hungary. Hankey's plan involved large-scale military operations carried out by a coalition of Balkan states with minor Allied assistance. The Russian request soon vanished in the mists, as the Tsar's armies pushed back the Turks in the Caucasus. Only Churchill had suggested a purely naval operation centred on forcing the Dardanelles and overawing Constantinople.

Nevertheless, for reasons that are not hard to identify, it was the latter scheme that recommended itself to the War Council. It promised the defeat of a significant enemy for very little cost. It would not require many British troops, the vast majority of which were committed to the Western Front as reinforcements for the shattered remains of the British Expeditionary Force. The only troops required would be occupation forces needed to garrison the Gallipoli Peninsula and Constantinople following the success of the fleet. It would not risk the Grand Fleet, as Churchill had assured the War Council that only Britain's old, surplus battleships would be used. The operation was also said to have the advantages of opening a supply route to Russia and galvanising the Balkan states into action on the Allied side. This last action could see a mighty army of Allied states advancing up the Danube and attacking the Central Powers from the rear.

On 3 January 1915 the War Council heard from Churchill that Admiral Carden was also in favour of the plan. In fact Carden had placed many reservations on the practicality of the plan. But these reservations that a great many ships would be needed, that the minefields in the straits would prove difficult to sweep, that the whole affair could be a protracted one were not passed on to the War Council by Churchill. So the War Council sanctioned the naval attack on the Dardanelles. Operations commenced on 19 February.

By mid-March it had failed decisively. The fleet proved incapable of overcoming the combination of minefields and mobile howitzers that protected the forts at the narrows. On 18 March a concerted attack on the defences by 18 battle ships resulted in one-third of them being sunk or disabled.

While naval operations were in progress, a debate had sprung up in the War Council concerning the role of troops in the campaign. This debate was instigated by Churchill who, immediately the naval attack commenced, started calling for troops to ‘reap the fruits' of the fleet's operations. It will be recalled that Churchill had sold the Gallipoli idea to the War Council largely on the fact that no troops would be needed.

What had changed his mind? This can never be known with any certainty. But it is possible that Churchill, who had some knowledge of military matters, had attempted to convert the government to a major operation in stages first the naval attack which would appeal because of its limited liability.

Then, when the fleet was engaged, call for troops of which were always going to be needed even if the fleet succeeded but which might also be required to help the fleet through the straits and to convert the whole operation into a real alternative to the Western Front.

If this was Churchill's motivation he can certainly be accused of involving the government by stealth in a much larger undertaking than they originally contemplated.

And it would be an operation to some extent under his own control and for which he would get the credit if it succeeded. To this extent his policy in initiating the Gallipoli campaign can be said to be self-serving. However, there is little doubt that his motives were more complex than this.

He had been one of the few members of the War Council to visit the Western Front, and to have witnessed firsthand the carnage that resulted from operations there. He had also been mightily unimpressed by the plans of the generals to break the deadlock. So Gallipoli seemed to him a way of waging war without the frightful toll of the Western Front.

Sea power and a few troops and Britain's (alleged) traditional way of warfare could be restored. Gradually the War Council became convinced that troops would have to be landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula to eliminate the forts and mobile howitzers. This would enable the minefields to be swept and the fleet to proceed to Constantinople whereupon the Turks would no doubt surrender.

What troops were to be used for these purposes and who would command them? Churchill insisted that the 29th Division (the only British Regular Army division not committed to the Western. Front) be an integral part of the force. Kitchener at first refused to release this division. Eventually, under pressure from other members of the War Council, he agreed that it should go. In addition Churchill promised the Royal Naval Division (a miscellaneous collection of surplus officers and men from the RN). The French (wary of British post-war aims in the Middle East) also offered a division. These forces were still deemed insufficient however. The only other troops on offer were the Australian and New Zealand troops in Egypt. These men (approximately two divisions), under the command of General Birdwood, were training in Egypt (because of lack of suitable facilities in Britain) before being sent to the Western Front.

In all the forces to be arrayed against the Turks amounted to approximately 70,000 men. The fact that at an earlier War Council meeting Kitchener had considered 150,000 men insufficient to defeat Turkey had apparently been forgotten.

Seventy thousand were available and 70,000 were therefore deemed to be enough. As Birdwood was considered too junior to command even a force of this size, Sir Ian Hamilton, a retired general then in command of home forces in Britain, was despatched on the rather inappropriately named HMS Foresight to take charge.

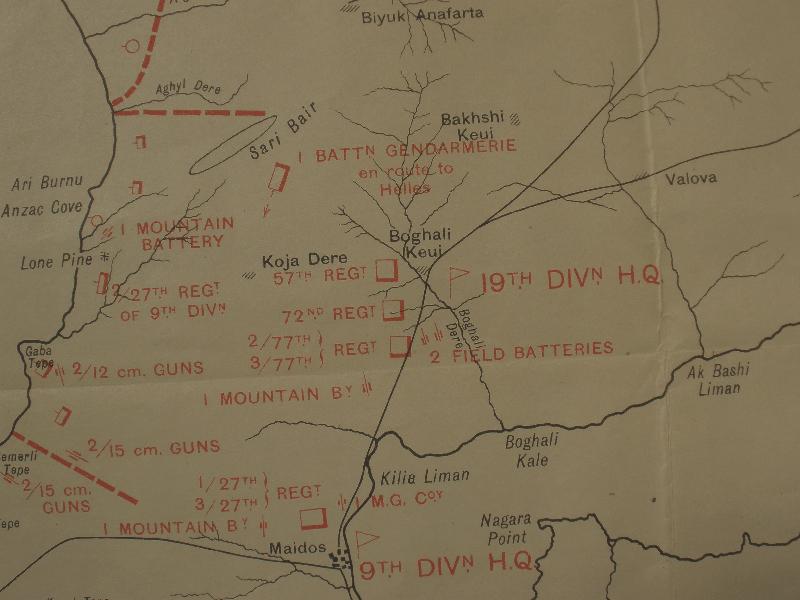

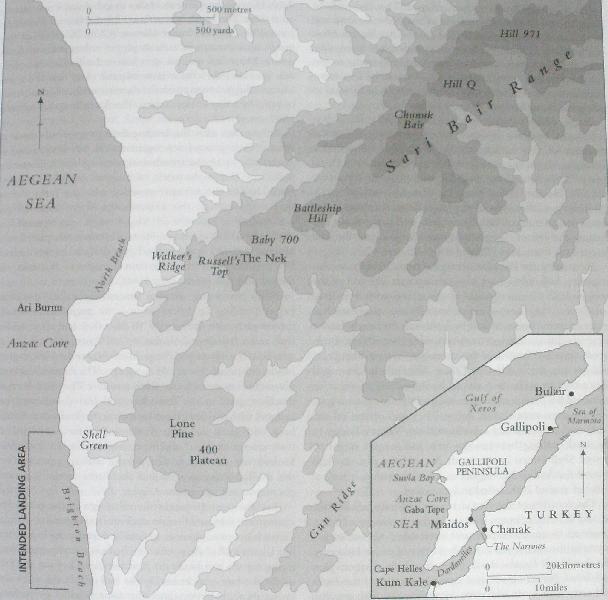

Hamilton's main problem was how to dispose his forces on the narrow confines of the Gallipoli Peninsula, the southern section of which was just over 20 miles long and five miles across at its widest point. In selecting areas to land Hamilton was very circumscribed. Much of the coastline consisted of rugged cliffs with few beaches or paths through the cliffs which could provide exit routes for large bodies of troops. He finally decided to make his main landing with the 29th Division on five beaches at the toe of the peninsula around Cape Helles. Once a landing had been established they would be assisted by the gunfire of the fleet to advance on the Narrows forts. To the north, the Anzac forces would make a secondary landing. A covering force would first seize the rugged Sari Bair Ridge. Then the remaining troops (protected by the troops on the heights from Turkish intervention to the north) would dash across the peninsula to Maidos. This would prevent reinforcements from being sent to the Turks at Helles, cut off any troops being driven back by the British, and assist the attack on the Narrows. Meanwhile the Royal Naval Division would attempt to deceive the Turks by a feint landing at Bulair (an obvious place to land at the narrow neck of the peninsula but because of that heavily defended). Meanwhile the French would land on the Asiatic coast at Kum Kale to destroy some heavy batteries which might interfere with the British landings at Helles.

This was an imaginative plan possibly the best that could have been devised in the circumstances. However, little thought was given as to whether 70,000 men were sufficient to defeat the Turkish Army or whether such forces as the Anzacs had provided enough men to occupy a long, precipitous ridge and advance across the peninsula.

Hamilton, who had been Kitchener's Chief of Staff in the South African War, never questioned his chief about the sufficiency of his force. Nor did anyone else in authority. It was merely assumed that the force at hand would defeat the incompetent Turks.

Because the troops for the assault had to be tactically loaded on the transports in the order in which they were to disembark, the landings could not take place until the end of April. Much has been made of this. It is claimed that the Turks greatly strengthened their defences in the five-week interval. In fact the Turks were remarkably supine in this period - a few extra troops were placed on the peninsula, and some extra defences constructed. However, rough weather in March and April would have almost certainly delayed the landings anyway. Troops could not have been landed or reinforced and supplied in a gale.

Meanwhile Birdwood was given the task of developing the Australian plan in detail. He had at his disposal one Australian division (Bridges) and the New Zealand and Australian Division (Godley), about 25,000 men in all.

Birdwood decided that to achieve surprise the forces must be assembled at night and landed at dawn. The 3rd Brigade (Sinclair-MacLagan) would land first as the covering force, push inland and establish positions on Gun Ridge.

The 2nd Brigade (McCay) would then land and seize the higher points on the Sari Bair Ridge (including the highest, Hill 971). The 1st Brigade (MacLaurin) would land immediately after the 2nd and act as a divisional reserve. Finally the New Zealand and Australian Division would be landed and a force assembled for the advance across the peninsula.

The Anzac forces began leaving Egypt in early April to join the 3rd Brigade on the Island of Lemnos, where it had been since 4 March. On the 12th they arrived and carried out some rudimentary practice landings. But there was little time for much training. The operation was to commence on the 23rd. In the event bad weather delayed it until the 25th.

On the eve of battle the 3rd Brigade was loaded on battle ships and destroyers the remaining brigades on conventional transports. From these ships the troops would first be loaded in ships' boats and then towed by steamboats until they were close to the coast. They would then be rowed ashore and landed on a 3000-yard front, the left of which was located just south of Ari Burnu Point.

At 3.30 a.m. on the morning of 25 April the battleships anchored about 3,500 yards off the coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula. It was pitch dark; not even the outline of the coast was visible. The order was given to land and the steamboats set off. At 4.00 a.m. the tows were cast off and the naval ratings began to row towards the beaches. As the troops approached it became obvious that the tows had bunched together and that the landing was about to take place about a mile to the north of the designated beaches, in a small bay to the south of Ari Burnu later known as Anzac Cove.

The reason for this mistake has given rise to endless speculation. It was suggested that the tides had carried the tows to the north, then it was found that in this area there were no tides of any significance. The battleship commanders were blamed for anchoring in the wrong spot. Naval charts show this was not the case; their navigation was correct. It has even been. suggested that Birdwood unilaterally changed the plan at the last moment to avoid under water obstructions protecting the original landing beaches.

The evidence for this is weak. The best explanation seems to be that the naval ratings guiding the tows lost direction in the dark and veered to the left. The result was that the whole force was landed on a narrow front with units bunched and intermixed from the start. The troops were also confronted by steeply rising ground instead of the more open country to the south.

In the event the covering forces failed to achieve their original purpose the capture of Gun Ridge. In the first instance this was not because of strong Turkish opposition.

Confronting the Anzacs were just two companies of enemy troops armed only with rifles. (Because of their commanding position, however, these men managed to inflict many casualties before they were driven back.) What prevented a coherent drive inland was the country rather than the enemy. The area the Anzacs found themselves in was unfamiliar. The maps available were so inaccurate as to be useless. So tangled and tortuous were the ravines and spurs in front of them that the groups that began to advance inland were soon split into small sections which lost contact with each other almost immediately. A few parties did manage to advance to the second ridge and a smaller number still reached their objective. But they were isolated and scattered and could provide no nucleus for any follow-up force.

Back on the beaches chaos reigned. The 2nd and 1st Brigades and later the formations of the New Zealand and Australian divisions had all landed around Ari Burnu. Most of the efforts of the officers were expended, not in organising a force for a drive inland as intended, but in trying to sort out the men into their original units. When some semblance of order was established, groups of men were sent forward to where the firing line was thought to be.

From mid-morning, however, the whole force was confronted by Turks in much increased numbers. On the morning of the landing the local Turkish commander, Mustapha Kemal (later, as Kemal Ataturk, to become President of Turkey), had been intending to exercise his force near Hill 971. He now redistributed his units for counter-attack.

At 10.30 a.m. the right of the small Anzac perimeter was driven in and most of 400 Plateau lost. In the afternoon and evening the left of the position was assaulted and the line driven back from Baby 700 and the Nek.

By evening the situation seemed serious. Bridges and his brigadiers had only a hazy idea of the exact position of the troops inland. Counter-attacks by the enemy were obviously under way. Many men, separated from their units and unclear of the situation, began to drift back towards the beach. Under these conditions Bridges recommended evacuation. Bird wood, who had landed in the afternoon, agreed. Hamilton, offshore on the battleship Queen Elizabeth, under naval advice that an evacuation would be impossible to organise, overruled his commanders and ordered the troops to dig in

This the men were already doing. They had driven off the Turks and were holding a position from Walker's Ridge in the north starting between the first and second ridges to around Shell Green in the south. All told the first day had secured the Anzacs 2.25 square miles of Turkish territory at a cost of around 2000 killed and wounded.

The tenacity of the Anzac troops, fighting in unfamiliar and difficult country, split up into a confusion of units, subjected to counter-attack and overlooked almost every where by the enemy, was certainly worthy of praise. However, this should not disguise the fact that the whole northern plan had failed. Before an advance could be organised the Turks had arrived in force and were occupying the high ground.

Nevertheless, it may be doubted if Birdwood and Hamilton's plan ever had a chance of success. It was absurdly ambitious to expect a force of two divisions to capture a succession of difficult positions along a ridge four or five miles long, advance four miles across the peninsula, capture more difficult positions and beat off counter-attacks after this had been done. Walking over the ground after the war C. E. W. Bean found the objectives almost impossible to attain in reason able time, even with the help of a Turkish guide.

While the Anzac landing was stalled the 29th Division was faring no better at Helles. They had suffered heavy casualties on the 25th and while the Turks had proved incapable of driving them into the sea, the regulars had proved just as incapable as the Anzacs of mounting a major advance. For the moment, however, Hamilton decided to concentrate his efforts in the south. A mixed force of Australian and New Zealand troops was sent to Helles to spearhead a new attack on 8 May. The result was a fiasco. Under the incompetent control of General Hunter-Weston (GOC 29 Division) the troops were thrown in without proper orders and with little notice. Many had no idea as to where the Turkish front line was situated. After the war it became clear that the main advance did not even reach the enemy trenches but had been stopped by a line of skirmishers. The Anzac brigades suffered 1800 casualties for no result.

In the days after the landing little progress was made at Anzac. Some ground was regained near 400 Plateau and in general the perimeter trenches were strengthened. There was never any chance, however, of a significant advance being made. In fact the initiative now lay with the Turks. Before they could exercise this initiative, the Anzac force suffered a considerable loss. On 15 May Bridges was wounded in the leg by a Turkish sniper. He was immediately placed on a hospital ship and evacuated to Egypt. Before the ship arrived, Bridges had died. His body was brought to Australia and buried on a hill overlooking RMC Duntroon.

With the Anzac advance successfully stalled, the Turks began building up forces around the perimeter to throw the invaders into the sea. By 18 May they had accumulated four and a half divisions, about 42,000 men. Next day they attacked. The result was the greatest disaster for Turkish arms in the course of the whole campaign. The Anzacs had been given time to consolidate their position. They had brought machine guns to the front line and had coordinated fire support with the fleet. By these means the Turks were beaten back with great slaughter. At the end of the day 10,000 of their troops lay dead and wounded on the battlefield.

So bad was the stench that a truce was arranged to bury the dead. Never again would the Turks mount a general counter-attack against the Anzacs.

For the next 10 weeks the campaign in the north was characterised by small-scale operations designed to capture a trench here and there or generally improve the line. It was not these small-scale operations, however, that proved most trying for the troops. As the heat increased in June and July so did the rate of sickness. By the end of July, the force was losing through illness about the same number every fort night as were lost in the initial assault. The major problem was dysentery. Sanitary conditions were poor; flies gathered in millions around latrines and rotting corpses. The medical services were overwhelmed by the number of cases and because the entire peninsula could be brought under enemy fire, had difficulty in setting up substantial hospital facilities. Nor was the food provided appropriate. The main fare was salty stew, hard biscuit and jam. Under these conditions the physical condition of the troops (superb at the landing) began gradually to deteriorate. This would have some effect on the next series of operations which were being planned.

Hamilton had decided as early as May that the growth of trench lines in front of the 29th Division and the French made large-scale operations at Helles prohibitive. The problem was essentially one of artillery. As had been discovered on the Western Front, entrenched defenders could only be blasted from their positions by a deluge of heavy artillery shells. At Gallipoli, there was never enough artillery to mount a considerable bombardment. The guns of the fleet, which were supposed to make up for this deficiency, could not fire shells with the plunging trajectory necessary to destroy trenches. Nor were their armour-piercing shells the optimum type to fire against earthen defences. So Hamilton's attention turned towards Anzac. Here, in the centre and the south there were trenches aplenty. But to the north the flank was open no defences barred the way to Hill 971. If columns could outflank the Turkish defences by stealth, there would be no need to bombard their trenches. The short age of artillery might be overcome. The next attack therefore would be launched from Anzac.

Reluctantly the War Council (now known as the Dardanelles Committee after the reconstitution of the Asquith Government in May) agreed. As a result of much debate it was decided to reinforce Hamilton by no less than five divisions (three from the Kitchener armies and two Territorial divisions). They would arrive in time to commence the attack in early August.

The main attack would be made from Anzac and was planned by Birdwood. His principal aim was to seize the high ground between Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair. Once this ridge was secure a drive across to the straits would be made and the Narrows forts captured. For the operation Birdwood was reinforced by the 13th Division and a brigade from 10th Division (both New Army formations raised by Kitchener from 1914) and one Indian brigade.

At the same time Hamilton made preparations for the continued supply of the northern forces through the winter.

Anzac Cove was very small and most supplies had to be landed at one pier. With rough weather in prospect and additional troops to supply, Hamilton proposed a second landing of two divisions on the flatter ground around Suvla Bay.

This area could then be used to accommodate stores to supply the Anzacs to the south. To the confusion of almost all historians since, who have not appreciated that the primary aim of the operation was to establish a base at Suvla Bay, Hamilton specified that when it had secured Suvla Bay as a base, this force should, if circumstances permitted, aid Bird wood's attack in any way possible.

The main attack was launched from Anzac on the night of 6 August. The plan was for two columns of troops to seize the foothills that commanded the routes to the summit of the ridge. Then two more columns would pass through them and capture the three major heights (from north to south, Hill 971, Hill Q and Chunuk Bair). Once these summits had been taken a force would move along the crest line down towards the Old Anzac perimeter. At the same time troops from Old Anzac would attack towards the main ridge. In this way the formidable positions of Baby 700, Battleship Hill and the Nek would come under simultaneous assault from two directions. When these attacks joined hands all of the main ridge would be in Allied hands and a drive towards the Narrows could be organised.

A diversion at Lone Pine by the 1st Brigade began on the 6th. It was designed to draw Turkish reserves away from the main battle. In every way it was a debacle. The attack was costly (over 2000 men killed) and by the time the Turkish reserves arrived it was clear that they were only facing a diversion. The Turkish troops attracted to Lone Pine were eventually used to help thwart the main advance. As for the main attack, the covering force succeeded in clearing the foothills, but the incredibly rugged nature of the country, the lack of good maps and the sheer confusion caused by a night attack ensured that the operation was well behind schedule when the main columns began their approach march. The left column, which was to capture Hill 971 and which had the furthest to go, never had a chance. The leading troops (4th Australian Brigade, commanded by Monash) were soon lost in the unmapped gullies and by dawn were nowhere near their objective. The right column (29th Indian Brigade and a New Zealand brigade) eventually got within a few yards of Chunuk Bair but was too weak to advance further. The first attempt on the ridge had failed.

After resting the exhausted troops on the 7th, a new assault on the summit was organised for the 8th. Some success was obtained with a New Zealand force actually occupying Chunuk Bair. On the 9th a further attempt saw Hill Q fall to a contingent of Gurkhas. Two summits of the ridge were now in Birdwood's hands. Neither was to remain so for long. The Gurkhas were shelled off the ridge by the Navy who in attempting to support the troops dropped a salvo of shells short. Then the Turks counter-attacked in strength and drove the New Zealanders from Chunuk Bair.

The main ridge was now completely in Turkish hands and was to remain so.

One further action of the August attack has burnt itself into Australian consciousness. This was the attack on the Nek. In the early morning of 7 August the 10th and 8th Light Horse, who acted as infantry, assembled for the attack.

A bombardment of the Turkish positions commenced. Then seven minutes before the attack was to go in the bombardment stopped. The operation was ordered by the local command to go ahead anyway, despite the lack of protecting shellfire and the absence of the New Zealand infantry who were supposed to assault simultaneously down the ridge.

Three lines of light horsemen went over the top only to be shot down immediately by the unhampered Turks. At the end of the day 375 of the 600 attackers had become casual ties. Of these 234 were dead. Their sacrifice was useless. The New Zealanders, as, we have seen, were not in any position to attack down the ridge to support them.

On the August operation as a whole there has been much debate. Some authorities have claimed that the August attack came within a narrow margin of success. While it is true that for short intervals troops did hold two of the key summits of the Sari Bair Range, these troops were very few in number.

In no sense can it be said that these forces ‘occupied the ridge'. After the machine guns of the New Zealanders on Chunuk Bair had been knocked out, they had nothing more than rifles with which to defend themselves. There was of course no artillery support. In these circumstances it was only a matter of time before these positions were lost to Turkish counter-attacks. To hold the positions in strength almost the entire force at Anzac would have been needed on the crest of the ridge, and given the nature of the country this would have taken many more days to organise than Birdwood had at his disposal. Turkish reinforcements could always reach the high ground faster from their side of the range than the Anzacs could from theirs.

The point also needs to be considered that it would have taken a very large force to occupy the entire range from Hill 971 to Battleship Hill. Even if this had been accomplished, supplying such a force with food and ammunition across the rugged and twisted ravines might have proved impossible.

The small number of men above the Apex on Chunuk Bair had received little food, less water, a negligible amount of rifle ammunition and no bombs. In any case, capturing the ridge and supplying the troops would not have marked the end of the battle. Birdwood's original plan saw this only as the first stage. The second stage involved pushing reinforcements across the peninsula under the cover of the force on Sari Bair. In August no reinforcements were available for that task, but it is doubtful if they could have been supplied with water had Hamilton been able to offer Birdwood an extra division. Finally, pushing forward from Sari Bair would not have been a simple matter. Although Sari Bair Ridge was the highest on that sector of the peninsula, there were still many difficult ridges to traverse before the Narrows were reached.

And the Anzac troops had proved that an enemy in control of the high ground did not necessarily mean that the troops lower down the slopes were automatically doomed.

The other debate concerns the role of the British forces landed at Suvla Bay. The troops landed on the night of 7 August. They suffered heavy casualties in the initial phase, especially among junior officers, and this factor, along with lack of water and clear instructions, delayed their advance on the hills overlooking the bay. By the time an organised advance was attempted the Turks were in control of the heights. Any further British advance was blocked. The fail ure of this force has often been said to have denied the Anzacs the support they needed to succeed. This scenario misunderstands both operations. As has been shown, the Anzac attack had not even come close to success. In addition, it was the main task of the Suvla force to establish a base for the winter. Then they were to secure the overlooking ridge. Only when they had accomplished these tasks were they to turn their attention to Anzac. In fact there was never any chance even if these objectives had been taken with expedition that troops in sufficient strength would have been available to negotiate the tortuous country between Suvla and Hill 971 and make a material contribution to Birdwood's operations.

The attempt to capture the Sari Bair Ridge in early August was really the last hurrah of the Gallipoli expedition-There was a great deal of confused fighting around Hill ,60 at the end of August badly handled and causing high casualties for a feature of dubious tactical value. But there ere to be no more large attacks.

Back in London the Dardanelles Committee debated the possibility of evacuation. In October they replaced Hamilton with General Sir Charles Monro who recommended that the whole force be removed. Hesitation in the face of this resolute advice led to Kitchener being sent out to confirm that Monro was correct. After further hesitation he did. Once more the politicians baulked this time because of a naval opinion that after all they could force the straits unaided.

This was rejected for the nonsense it was and it was finally decided in December to withdraw the troops. The wisdom of this decision had already been confirmed by a great storm which struck Anzac in November. Gales, sleet and finally snow caused over 3,000 cases of frostbite and trench foot, washing away some of the trenches and causing a great deal of discomfort and misery.

The evacuation, which was largely planned by Bird wood's Chief of Staff, Brigadier-General C. B. B. White, has been hailed as the best-executed operation of the campaign.

It was certainly a masterpiece of planning. The troops were removed over a period of several weeks, various ruses being employed to convince the Turks that the line was still solidly held. Eventually, on 19 and 20 December, the evacuation of Anzac and Suvla was complete. There was hardly a casualty. Whether the success of the operation was due to the planning or whether the Turks, remembering their experience of 19 May, were reluctant to attack in the open an enemy that was in any case departing, cannot be stated for certain.

Whatever the reason, the Gallipoli experiment was at an end.

The Gallipoli operation cost 26,111 Australian casualties of whom 8,141 were killed. In addition New Zealand lost 7,571 men of whom 2,431 were killed. (Britain lost a total of 120,000 casualties at Gallipoli and the French 27,000. The Turkish total is very speculative probably about 220,000 with a much higher percentage killed.) To what end did these men die? It has to be said that Gallipoli had no influence on the course of the war as a whole. More depressing still, even if the expedition had succeeded in its aims, it is doubtful if the war would have been shortened by a single day. The problem was that the premises upon which the operation was based were very dubious. The planners never doubted that if the fleet got through to Constantinople the Turks would surrender. There seems to be no evidence for this. The Turkish government was certainly making every sign of defending its capital.

What would have happened had the fleet arrived and the Turks fought on? Could the fleet have been supplied? Would the British have reduced Constantinople to rubble? Even had the city fallen little need have followed. The Turkish government might have decamped into the interior of Anatolia and fought on. In this scenario would the Balkan states have been so impressed by the fall of Constantinople that they would have rallied to the Allied side? It seems unlikely. It is far more likely that they would have been impressed by the series of mighty defeats inflicted on the Russian armies to their near north by the Germans in this period.

Even had the Balkan states joined the Allies, their accession would have been a dubious advantage. Their peasant armies were under-equipped (and the Allies had no surplus equipment with which to supply them), ill-trained, poorly led and fractious to a degree that must have placed any long-term cooperation between them in doubt. Nor were communications along the Danube sufficient to sustain large armies for considerable periods of time. In any case the Austrians had the line of the Alps to sustain them in the unlikely event of these peasant levies driving them back.

Finally, none of this had any implications for the German Army on the Western Front. This Army was the main engine of the war for the central powers and the Western Front was the main theatre. The Germans would have to be defeated in north-western Europe before the war could end.

As far as the Anzac troops were concerned, the only thing to be said for the Gallipoli operation was that it kept them away from the Western Front for at least a year. Had they arrived in France in early 1915 their casualty list (as operations around Pozieres would subsequently prove) would certainly have been much higher than it was at Gallipoli.