Topic: AIF - DMC - Scouts

Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance, Part 9

Frederick Allan Dove

3rd Light Horse Brigade Scouts in the hills at Tripoli, December 1918

In 1910, Major Frederick Allan Dove, DSO, wrote a book on a subject he was very familiar with through practical experience called Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance. This book set the intellectual framework for the formation of the Brigade Scouts during the Sinai and Palestine Campaigns as part of the Great War.

Dove, FA, Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance, 1910.

II. - Scouting For Information Or Tactical Reconnaissance By Patrols.

General Remarks.

Reconnoitring Patrols are parties detached from a halted or moving force to obtain information. Their sphere of action is beyond the line of Outposts or the Screen referred to in I. Being without support and in constant danger of meeting superior hostile forces, their action must be chiefly of a "stealthy" nature. They rely for safety in an emergency on the sharpness of their eyes and ears, the quickness of their wits, and the speed of their horses. The number of men told off to form a Reconnoitring, Patrol will vary according to the work to he done, but they larger the number the more risk of detection and failure. Three or four men and a leader make a handy patrol; really good Scouts, who have confidence, in themselves and on another. will prefer to work in pairs. Occasionally strong patrols of from 12 to 100 men are sent out on some -special mission, but even then the actual Scouting will he done by two or three small squads of Scouts, the remainder being really an escort or support.

"Scouting" in its true sense is the work done by the individuals composing the Reconnoitring Patrols. It is an art, and can only be acquired by a limited number of men who possess the natural gifts of body and mind. Out of a squadron of picked Australians who went to South Africa, not more than twenty men became good Scouts, and only half were really first-class. Yet at the beginning a hundred men in that squadron believed that they were born Scouts. After a few experiences they were mostly very willing to let somebody else do the work.

'From my reading and experience I conclude that there should be a thoroughly trained Corps of Scouts at the disposal of every General to do the dangerous and difficult duty of reconnoitring.

1. - Composition of Patrols.

Reconnoitring Patrols should be composed of trained Scouts, drawn either from regimental establishments or from the Corps referred to above. A signaller or two with equipment may sometimes be attached. A cavalry pioneer with means of hasty demolition has been found useful with a patrol, but properly trained Scouts could do this work themselves.

It must always be borne in mind that to include in a patrol any person who is not himself a trained Scout is an encumbrance and a danger.

It is it great advantage or the men to have practised and worked together. Scouts should be organised, there fore, into permanent patrols of four. Two or more "Fours" can be combined when larger patrols are required.

2. - Preliminary Instructions and Preparations.

The patrol leader detailed for a reconnaissance should receive very explicit instructions, as to

(1) the object of the reconnaissance - that is, what he is to report on;(2) when he is to start and when reports will be expected;(3) to whom and where reports are to be made;(4) what is known of the enemy;(5) whether friendly patrols or troops are likely to be met.

The instructions should be supplemented by a sketch or by reference to a map. If our column is likely to march during the absence of the patrol, the leader should be informed.

The leader next decides on the route to be taken (when this has not been prescribed), by reference to the map, a view of so much of the country as can be seen, or by his local knowledge, or by a combination of those.

Next he retails to his men the instructions he has received and the plans he has formed, taking them very fully into his confidence, in order to arouse their interest in the mission and to secure their intelligent co-operation. He now has a final inspection of his own and his men’s arms and kits and horses, to see that everything is in good order and that nothing is carried which will glitter by day or rattle by night. The patrol then sets out.

3. - Formation o f the Patrol, by Day.

The formations of a patrol of four by day have been gone into fully in I., Section 11. The same principles govern the organisation and movements of larger patrols.

Organisation of the Patrol-that is, the allotment of definite duties to individuals-should never be neglected. The leader should remember that he is the head and brain of the patrol and the Chief Observer; he uses the other members to protect and assist him, but must not rely on their conclusions; he must always see for himself.

The more compact the formation of a patrol the better the chance of avoiding detection, but the greater the possibility of all being shot down or cut off. Therefore, the leader must study every bit of country with a view to what is best to be done in each case. In thick bush or forest the only possible formation is Indian File, the men following the leader more or less closely.

It will frequently be advisable for portion of the patrol to remain halted (dismounted) in concealment while one or two Scouts examine doubtful localities. 4. Formations at Night.

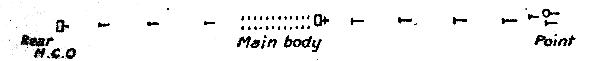

The only formations for dark nights are File (twos) or Indian File. The commander leads, and has with him a very keen Scout and a horse-holder. Then follow the Scouts, singly or in pairs. A non-com. or very trustworthy man brings up the rear. When the patrol halts, a Scout previously detailed moves out a few yards to the right, and similarly another to the left. These men leave their horses with their mates. If a patrol is so large that the tread of men or horses and rattling of equipment is likely to interfere with the hearing of the front and rear Scouts the advanced " point" and the rear man are kept well away from the main body, connection being maintained by links," thus:

The links must be clearly visible to each other, and near enough to pass quietly spoken orders or messages.

The leader must largely devote himself to maintaining the required direction. He, therefore, has with him a good .Night Scout. Note that some excellent day scouts are not at all reliable at night. This Scout must be relieved every hour or so, as the strain on his eyes, ears and nerves is very great.

Halts are frequent at night. During these it may be necessary for the leader and his nearest Scout to go ahead some distance on foot to examine a suspicious object, hence the need of the horse holder. The N.C.O. at the head of the main body should be informed when the leader leaves and when he returns.

Previous: Part 8, Screen To Rear Guard

Next: Part 10, Finding One's Way

Further Reading:

Obituary, Frederick Allan Dove

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: Brigade Scouts, Scouting or Protective and Tactical Reconnaissance Part 9 Scouting For Information