Topic: Tk - POWs

Ottoman Service Records and the treatment of Mehmet

Within Turkey today when examining war memorials devoted to the Great War, one absence is quite noticeable. There are no individual names recorded. At first this was tied to the cult of personality in the form of Ataturk.

In the last decade beginning in the mid 1990's, there has been a relaxation of this cult and the names of individuals are rising to the surface. To its great credit, the Turkish General Staff has put together a five volume work called "Sehitlerimiz" or "Our Martyrs" which provides the details of the Ottoman and Turkish soldiers who have died in service to that state. There are many names missing from this list but it is a good foundation and the Turkish General Staff are to be commended for putting forth this research into the public arena.

There were two chronic problems with Ottoman record collection regarding those who died in service during the Great War.

The first related to the fact that record keeping was decentralised. The initiating roll book of the town in the province from whence the soldier was the solitary only record within the Ottoman system which maintained something akin to a service file. All actions that related to that particular soldier that generated a record ended up with that particular roll which was amended accordingly to keep in line with the change in status. In theory, this is most the most effective way of keeping contact with the soldier and the relatives and finally any post war entitlements. However, it relies upon three variables which the Ottomans rarely had under their control:

1. The location of the record within the Ottoman Empire;

2. The ability to maintain that roll through the postal and delivery service within the Ottoman Empire; and,

3. The ability of the unit to which the soldier belonged to make such a report.

Post war Turkey had many provinces and towns severed from it and distributed to other nations. With this dismemberment went also the roll books held by those towns. Many disappeared or were deliberately destroyed. Within Anatolia, similar events occurred, especially during the periods of expulsion of various invaders. That we have any surviving records is in itself testimony to those few Turkish clerks who understood the value of their records and protected them accordingly.

During the war, the lines of communication were poor at the commencement and as the war ground on, were degraded considerably further. Thus it was a hit and miss affair for a piece of information to arrive at the appropriate destination.

Finally, if the unit to which the soldier belonged was destroyed, captured or fled without their records, then anything relating to casualties would not be transmitted. When records fell into Allied hands, they went to the Inteligence Section for translation and analysis. The records were not returned to the Ottoman authorities afterwards.

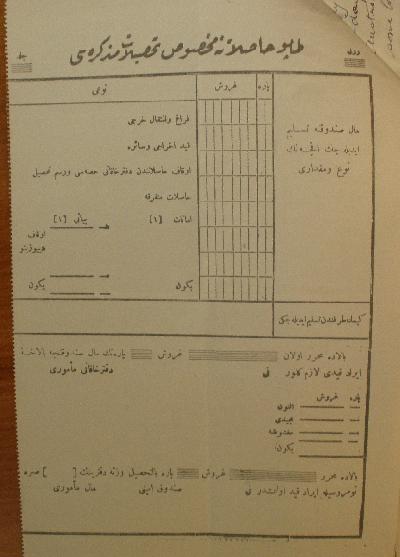

The capture of Ottoman documents was always a good day for the fortunate Regiment involved in receiving them. Paper that was obviously of no value to the Intelligence Section were snapped up as writing paper as there was a huge shortage of paper in the units. Above illustrates the situation. This captured Ottoman page contains a proforma accounting document originally set in a book with perforations that allowed the original to be separated and sent to the relevant authority. It was captured at Damascus and this particular page including others from this book were recycled as part of a report on the action at Kunietra in September 1918. This illustrates how Ottoman paper was employed once it was captured and formed part of war booty for the Allied Regiment.

An example of how this played out. Two battalions of the 81st IR were captured at Magdhaba on 23 December 1916. While there were nearly a hundred Ottoman deaths at this battle, not one death has been recorded within the Ottoman files. Hence we have no idea as to who these men were or where they came from. All the records relating to this Regiment were captured and so nothing was sent to the town rolls and so they were not amended to reflect the status post 23 December 1916.

To give an illustration of the enormous proportions of this problem, when 12,000 Ottoman troops surrendered at the Baramke Barracks in Damascus, 1 October 1918, they were confined to a POW camp which was poorly administered. Quite quickly, a cholera epidemic broke out killing many people, Allied and Ottoman alike. However, because of the conditions at the POW camp, at the height of the epidemic, over 100 deaths per day were recorded. Once the epidemic had been controlled and no one died of cholera any more, nearly a thousand Ottoman soldiers had died. To dispose of the bodies, mass graves were dug and the men tossed in. Below is a contemporaneous picture of this event.

The picture was taken at Damascus in October 1918 at the height of the cholera epidemic.

The reality is that none of the men in this pit was ever recorded for the Ottoman rolls. They are just nameless men buried in a pit.

This was the fate of many Ottoman soldiers who died as a consequence of service to the empire.

At the end of the day, the records held by the current archives dealing with the deaths of Ottoman soldiers during the Great War reflect at most about 10% of the total deaths leaving about 90% of the Ottoman casualties without a name or a known place of burial.

As remains of Ottoman soldiers are found around the old battlefields, we can only guess as to the origin and unit of these men. They too will remain nameless as individuals.

The German records are a little better but the KuK (Austro-Hungarian) are just as good as the Ottoman records.

Citation: Ottoman Records - Serviceman's death records