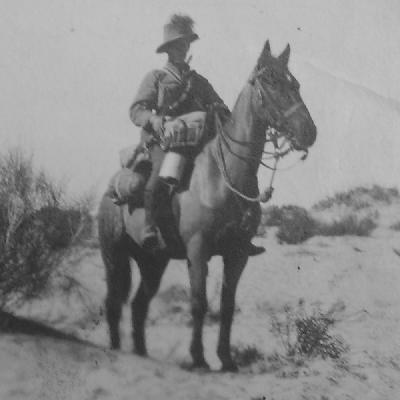

Topic: AIF - DMC - Scouts

The Australian Light Horse,

Light Horse Duties in the Field, Part 1

Scouting for Troop Leaders

The following essay called Light Horse Duties in the Field was written in 1912 by Major P. H. Priestley, who at that time was on the C.M.F. Unattached List. The article appeared in the Military Journal, March 1912.

Prior to that Priestley served in South Africa 1901-2 with the 5th South Australian Imperial Bushmen in Cape Colony and Orange River Colony and was awarded the Queen's South African Medal with four clasps. During the inter war years he served with the South Australian Mounted Rifles 1900 - 1910 when he was placed on the unattached list. At the outbreak of the Great War, he enlisted with the 3rd Light Horse Regiment and embarked with "A" Squadron. He was Killed in Action on 3 May 1918.

The following is a 3 part series of this article. A fourth part was attached as his article was critiqued by Major F. A. Dove, D.S.O., A. and I. Staff, in the Military Journal, May 1912. Both articles give valuable insights in the basic thinking around the use of Light Horse scouts, detailing both theoretical ideas peppered with experience wrung from the recent war in South Africa.Priestley, PH, Light Horse Duties in the Field, Military Journal, March 1912, pp. 171 - 185.

Light Horse Duties in the Field

Scouting.

(1) Scouting for Troop Leaders

No body of men, however small, should at any time cross the picquet line without having a scout or scouts between it and the enemy. The purpose of these scouts is primarily to become a preventive against surprise. This form of work is the simplest form of scouting, and when acting with the detached mounted troops, all intermediate steps are to be found amongst the operations, between it and the highest, which is that of specially selected scouts acting for some special purpose.

With light horse, every N.C.O. or man who is with his troop usually undertakes at various times at least this step in scouting, so that it can be said of this arm that they are essentially scouting troops. Even in this elementary work is to be found scope for the excellence of a few men over the others, and these men of greater ability become selected for unusual duties of varying importance, till, ultimately, the exigencies of active service not infrequently cause these men to be permanently detailed for the work.

There is no method of working which can well be laid down for scouting unless it is that the scouts should keep well out from their troops, well extended, always in touch, never out of sight of the troop, and always keep their eyes open.

Troop leaders will not be employed in elementary scouting, but it is the troop leader who must instruct his scouts and direct them in their work, and for this reason he should be familiar with scouting in all its branches. Even in the daily work with the guards he cannot assist his scouts, nor work in harmony with them, unless he thoroughly understands the principles.

A troop leader must always support his scouts and see that they are never in want of assistance. Scouts have very difficult work to perform, and it is not every man who will desire to ride up a rise almost alone when an enemy may he expected on its summit. Of course, the general principle of scouting may be looked at in this way: that it is better to sacrifice one or two men than to sacrifice a troop; but this is not the correct aspect of the cage. There is in reality no need to sacrifice at all. There is, of course, always the chance of meeting a murderous fanatical individual who will throw away his own life or freedom for the sake of shooting or killing a scout; but in the ordinary run of warfare, this elementary scouting, if properly carried out, is no more dangerous than ordinary troop work.

Scouts must have thorough confidence in their troop leaders. A scout must know that if he meets with trouble he will not be left to get out of it himself as best he can. If he knows he is being watched and protected, he will work more confidently and with a more free use of his opportunities.

Troop leaders should be always on the look out for signals from their scouts. Series of signals between scouts and their officers may be of use, but usually are unnecessary. The troop leader is, in any case, following his scout or riding parallel to him, and there are only two signals needed, either to assist or to retire. The evidence as to the necessity of the latter is too obvious to need a signal in addition, and consequently any signal made by the scout must be read as indicating a wish on his part for the support of the troop.

An officer may wish to signal his scouts, but a whistle to attract attention, and the signals of silent drill, are all that are required, except a signal to "come in." The correct signal to recall scouts would be, perhaps, the “close," but in the screen, where all the troops are in open order and the squadron separated, such a signal being applicable to all who see it may lead to confusion. A very simple and convenient signal of recall to scouts is made by holding up the head-dress at the full extent of the arm, or better still, by holding it up on the muzzle of a rifle.

If a scout wishes to signal his troop leader he cannot order an increase of pace by signalling the command “trot," or other signal of command. He may however, use the signal of holding up his head-dress on the muzzle of his rifle to indicate a desire for support, i.e., the presence of the troop leader at the post he is on. This is simple, but it is simpler still if the troop leader trots up at once on seeing any unusual movements on the part of his scouts. There is no need for him to wait till the scouts have formed an opinion as to the desirability of calling him up. The troop leader does not wish to act on the opinions and judgments of his 'scouts, but on his own. Not their judgment on unusual incidents, but the occurrence of unusual incidents is the matter he wishes knowledge of from his scouts; and since unusual movements of his scouts must be caused by some unusual circumstance, these movements are in themselves the indication he wants; and he should press up to them at an increased pace at once, without waiting to know if the scouts think the circumstances under notice are of value or not. Any elaborate series of signals from scouts to troop leaders in the screen are unnecessary, as all the latter has to do is to increase his pace and see for himself.

The evidence of the necessity for retirement or the checking of a troop that has been termed too obvious for a signal in addition, is heavy rifle fire, or this following on the capture of a scout. Heavy rifle fire, not the fire from guns, is the only legitimate reason for a troop checking its movement. The capture of a scout is in itself not sufficient reason, it must be followed by heavy rifle fire that is too severe to permit of a rescue.

That is the standard rule, but without paradox, the exact converse of the last sentence is an urgent reason for checking the movement of even a troop of the advance guard and placing it under cover. If the capture of a scout is seen, and absolutely no rifle fire at all follows on the troop increasing its pace, the troop must be checked and taken to cover before it enters the zone of effective fire of the occupied position. The correct inference is that the enemy know they are sufficiently strong and securely placed to crush the troop in the attempt at rescue at close range. Reserved fire after disclosing the occupation of the position is an indication of strength. In other words, the enemy, who can see the positions and strength of both forces, indicate their belief that their ambush is effective by reserving their fire for close range, as opposed to the principle of the defence, keeping the attack at long range. The troop leader who encounters this special case must halt under cover and send back word of the nature of the occurrences to his squadron leader, that he may get his squadron well in hand before making the attack; and if he considers it advisable, he will report to the brigadier, so that the advance can be made under the cover of shell fire from the column.

Though the position and presence of the ambush have been indicated, yet the strength of the force in occupation has not, since there has been no rifle fire. It is to he taken that this force is not inferior to the troops which are immediately supporting the scouts, and that it is prepared to deal with them in a similar manner. It is absolutely necessary that the support be strengthened, and this can be done by delaying the advance guard till the main body of the column is in close touch so that the movement to the attack can be under the eye, and possibly direction, of the brigadier.

For this reason, if for no other, a scout must never place a skyline between his troop leader and himself, though this does not include the case of one or two scouts of a section whose other members remain in sight and are in close touch with them. A troop leader has to judge by the actions of his scouts, not by the messages they send back, and how can he see them if they cross a skyline? If a scout is captured, it should be in full view of the troop leader, so that he can see what has happened, as in this case, least of all, it is not possible for a scout to send other signal or message.

A troop leader will avoid sending scouts where he would not go himself. In ordinary work, an officer leads his troops into action, but he sends his scouts.

He must, consequently, never send them so that they bear the brunt of an action, but must only use them to find the enemy. In other words, if the troop leader expects, from some tangible reason, to find the enemy on a certain position, it is not for him to keep out of range and send on his stouts, and then when they are fired on, to wait where he is for support to comma up. Sending his scouts to his front necessitates that a troop leader be prepared to follow at a gallop at any moment. It is even better, on perceiving this tangible reason, that if a glance around shows him to be well in touch, to gallop at once.

In screening, scouts are for the purpose of finding out whether positions encountered are occupied by the enemy. By scouting the ground the troop is enabled to move forward at the even pace of the column it protects, knowing that the enemy must disclose itself in sufficient time.

The value of scouts may be appreciated when it is remembered that a troop of fifteen or twenty men is moving over hostile ground at a considerable distance or interval from any support. Yet scouting affords sufficient cover for a troop to 'work under, as long as it is in touch. If it is properly done, not only is the troop leader warned of an impending attack, but the enemy is prevented from estimating the value of the force opposing them. When the scouts occupy the sky-line between the troop and the enemy, the latter cannot form any idea of the force covered. It may be an isolated troop or one with a large support at hand; and while this cannot be determined, an enemy will always hesitate to attempt to cut off.a troop. What the guards are to the main body of a column, so are the scouts to a troop.

The system of utilizing smaller bodies of troops to seek out the enemy and to cover the advance of larger bodies supporting them is universal in the advance of an army. The outermost body of all is the chain of scouts, and the term scout may be defined as being the component of the extreme outer fringe of the screen of a moving army. There is nothing outside this line, unless, indeed, it be the single man sent out by the N.C.O. of a scouting section to ascertain the friendliness or enmity of a hesitating body of unknown men in front, or special scouts detailed for special work.

Scouts must be placed between every troop of the screen and the enemy, on whatever sides of it that may be exposed, so that it is not possible for an enemy to attack it unobserved from any direction. The task of a troop leader in the screen is a difficult one, and he can only execute it by taking every advantage the ground affords. He himself must be responsible for touch with his support by moving his troop in unison with it, and must occupy all positions within rifle shot between him and the enemy with his scouts.

A troop leader should always train his scouts to work in touch with his troop alone, except in the special case of the flank guard advance troop, and to take their direction from it only. By this means, he can at once change their objective to any position, or away from it, as he himself decides it is within the scope of his work or not, by wheeling the troop to a distinct angle towards or away from it, and can push them out or stop them by increasing the pace or halting for a short interval.

Scouting varies in certain particulars with the guard duty with which the troop is engaged, but the principles are the same, and a good scout is equally at home with them all. All scouts will work at a wide interval, about 150 yards, or not less than 50, but on attaining the summit of a position and while awaiting the oncoming of the troops they should move in to occupy its most commanding point. Troop leaders must remember that scouting is a difficult duty, and must see that scouts are afforded every advantage chance offers. It is preferable as a rule to move a troop at its own inconvenience to save the scouts from difficulty in negotiating the features of the country, rather than the converse.

Whenever a troop leader reaches, the summit of a hill or other high ground, he should halt his troop below the sky line and dismount the men to rest their horses. He himself should take this opportunity of examining the country before him with his glasses, and of observing the movements and position of the main body and troops co-operating with him. He should also endeavour to find his position on his map, and to identify with it the most prominent features of the landscape.

During this examination of the country through his glasses should the troop leader believe that he can see a convoy, or a force of troops at such a distance that its existence may be doubtful, he should mark its position, and after completing his survey should redirect his attention to it to ascertain if it has moved at all.

No troop leader should ever work so that he is in any way depending one troop of another squadron for scouting. This particularly applies to troops in the screen near the junctions of the several guards.

A fundamental principle of the system of using scouts in the screen is that they shall prevent the occurrence of the unexpected. Therefore, a troop leader entirely misses the object of his duty if he does not use scouts in a certain direction merely because he does not expect to encounter the enemy there.

A troop leader should see that his scouts are detailed for duty as soon as possible after he himself is. If the scouts are allowed to move off at once they have leisure to scout the opening positions carefully, a not unimportant point when the enemy have had the previous night to arrange their plan of operations. Scouts always work better if thus at the outset they move off in their own time instead of being rushed out at the last minute to get ahead of the troop.

When a troop attacks at a gallop it usually happens that its scouts are ahead of it, and so become apparently a small force charging in front of the troop. It is, however, one of the little differences between practice and theory. If fire has been drawn the scouts will probably be hesitating while the troop increases its pace. If fire has not been drawn there is no disadvantage in having them in front, but rather the contrary. The principal thing in an occasion of this kind is that the charging troop shows a bold determined front, and if the scouts are not in front of it they will be with it. Scouts, will always keep with their troop in the firing line, and remain there until ordered out again.

Previous: Brigade Scouts

Next: Part 2, The Scouts of the Screen

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Light Horse Duties in the Field, Part 1, Scouting for Troop Leaders