Topic: AIF - Lighthorse

The Australian Light Horse,

Militia and AIF

Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 7, Night Operations

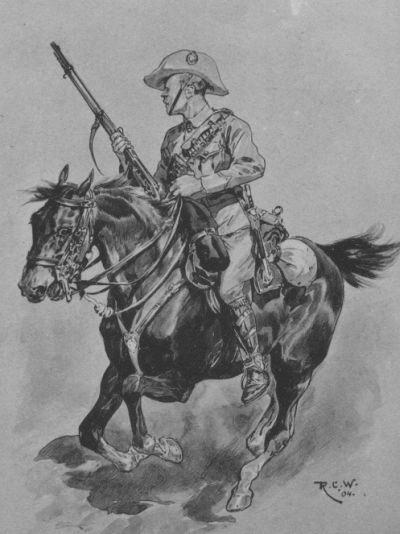

Cape Mounted Rifleman

[Drawing from 1904 by Richard Caton Woodville, 1856 - 1927.]

The following series is from an article called Mounted Rifle Tactics written in 1914 by a former regimental commander of the Cape Mounted Riflemen, Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Collyer. His practical experience of active service within a mounted rifles formation gives strength to the theoretical work on this subject. It was the operation of the Cape Mounted Riflemen within South Africa that formed the inspiration for the theoretical foundations of the Australian Light Horse, and was especially influential in Victoria where it formed the cornerstone of mounted doctrine.

Collyer, JJ, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Military Journal, April, 1915, pp. 265 - 305:

Mounted Rifle Tactics.

V - NIGHT OPERATIONS.

Authorities as to importance - Reconnaissance - Training - Night movements (tactical) - Rests - Pace - Supervision - Information - - Secrecy - Order of march - Night combats - Difficulties - Small raids -Important points -Encounter combats - Summary.

Night operations have been a feature of every protracted military enterprise since the time of Gideon, who succeeded with a small force in beating his enemies by the device of the lamps and pitchers. Wellington said that 49 night attacks upon good troops are seldom successful "; but he was compelled to attack strong fortresses at night in the Peninsula to obtain important results. Lord Wolseley has written that "night attacks can only be attempted when the attacking army is highly disciplined and well led by tactically well-instructed officers," and has recorded his belief that the army " which is first able to manoeuvre at night will gain brilliant victories." Comparatively recent events in the Far East go far to corroborate his statement. Field-Marshal Sir John French, summing up after a lecture on the subject at Aldershot, said:-

"Proficiency in the practice of night operations is an absolute essential to the successful conduct of war as it is to-day. If, of two forces, one is trained in the performance of night operations, and the other is not, the former will have an enormous advantage over the latter."

We must, therefore, accept capacity to work during night as a condition indispensable to any force properly trained for war. Effective night work will, as a rule, be based on efficiently performed reconnaissance, which, as I have already said, is one of the chief duties of mounted troops. This makes it necessary that leaders of mounted troops should be aware, not only of the correct mode of employing their own arm at night, but that they should have a good knowledge of night operations as they affect every arm of the military service.

We find, in reference to night operations, by those best qualified to express an opinion, a distinct note of warning as to difficulties which may be anticipated in their performance. Each of the remarks which I have quoted above clearly indicates the opinion of its author that certain favorable conditions must be obtained to make night operations effective.

It may be suggested that the South African Forces, especially the mounted troops, will, by the circumstances of their every-day life, be well fitted to work at night. Those accustomed to the veldt may perhaps be especially well able to find their way about by night as well as by day, but, as I have said, a more general civilization is depriving the citizen soldier of many of the advantages in a military sense possessed by his forbears, and I wish to quote again the words of a famous general of the Republican Forces, when he said with regard to his preparations for a night march of six miles with 600 mounted men, "it cost me considerable thought to arrange everything satisfactorily." Therefore the need for special training exists, and must be met.

The citizen troops of South Africa must be trained to meet possibilities, and he would be a bold man who would say that South Africa will not need to employ troops in comparatively large bodies in certain eventualities. In discussing any military operations as possibly to be performed by the troops of South Africa, we must take into consideration columns of more than 500 or 600 mounted men, and be prepared to handle forces containing; some infantry and in bodies of some considerable size.

The larger and more varied in composition a force is, the more difficult it becomes to control and move it, and what may perhaps be a perfectly simple movement to arrange with a small column composed of troops of one arm, becomes a far more complicated business when numbers increase and several different arms have to be dealt with.

The term “night operation” is correctly applied to any military operation which can be carried out at night, and covers a wide field, and I propose to confine myself to night movements and night combats.

Night Movements -

I do not wish to deal with ordinary night marches, which have no tactical consideration to govern our discussion. I propose to consider only those movements which contemplate a definite action against an enemy, or during which an encounter with an enemy may take place. A night march of the first kind is probably undertaken to reach a given spot at a given time, and then to take up a previously chosen position with the object of fighting the enemy, either by attacking him, or frustrating his advance. If we study instances of night marches, u e shall find that previous reconnaissance of the route is by far the most satisfactory method of providing for them, but, of course, this may not be possible, and then reliance must be placed on guides, or the route must be determined, and then followed on the map with the aid of the compass or stars.

It must be accepted that if the ground to be traversed is difficult and intricate, unless a complete reconnaissance has been carried out or some one with sound military knowledge is available to guide the force, the venture will most probably fall short of a successful issue, as a result of not knowing the whole ground thoroughly.

“Every commander who orders a night operation, which is not preceded by a complete reconnaissance, increases the risk of failure and incurs a heavy responsibility." (Field Service Regulations.)

A night march is always in many respects more exhausting than one in the daytime, very largely because the strain and uncertainty act through the nerves on the physical energy. On the other hand, in summer animals will move with less distress to themselves by night, and, of course, the cover afforded by darkness gives great value to night movements.

Constant rests, during which all mounted men should invariably dismount, and supervision of the column are necessary, and the time allotted for the march should allow of rests at definite intervals for fixed periods. This has all to come off the total time allowed for reaching the spot or force which is the objective, and must therefore be carefully calculated. These rests should be made the opportunity for staff officers to go along the column and check its condition, rectifying errors of position, distance, and so on. The defeat at Stormberg is largely attributable to neglect of the physical condition of the troops. They should be rested and prepared for such an undertaking as a night march, for the possession of all their mental alertness and physical energy has a large influence in the direction of success. Jaded troops are useless at the end of a trying night.

The pace of the column is that of the slowest moving unit in it. Mounted riflemen should be well aware of what can be expected from artillery and infantry at night in respect of the rate of marching. The complete ignorance of the guides at Stormberg as to what infantry could do was again a factor which contributed substantially to the failure of the enterprise. They were mounted policemen who knew nothing of infantry troops, and had no expert to question them as to facts, and draw his own inferences as to what in a military sense was possible. Grave consequences may ensue if thorough military knowledge is not at hand to supplement the efforts of local guides, who should merely be relied on as to facts, such as the position of roads and actual distances. The question whether the performance of any military task is possible should be decided by those who possess expert military knowledge.

The march must be supervised by an unceasing watch and check by staff officers. The necessity for this is at no time more marked than after a pause in the march. The need for this was brought home to me, on one occasion at least in the South African War, when after moving off after a halt I failed to hear the noise of wheels behind me after marching for some distance. As staff officer to the column, I rode back and found the drivers of the leading pom-pom mule team asleep, and the whole portion of the column behind them still waiting the order to move. The forward movement had been resumed by the leading portion of the force so quietly that the troops behind the pom-poms had not heard it. The more varied the component parts of the force, and the larger it is, the greater the chance of such mishaps.

It is essential that each individual, who is to be charged with any share in the execution of the enterprise, should know as much as is necessary to enable him to perform that share properly. This is, of course, necessary in all military undertakings, but becomes especially important in night operations. Darkness means loss of power of supervision and accidents, and events assume exaggerated proportions in the doubtful atmosphere of night.

The habit of moving at night and of identifying features in the darkness and, in fact, of being at home in circumstances when objects and conditions, easily recognisable and familiar in daylight, become strange, and the imagination has full scope, must be cultivated deliberately, if it is not possessed. Most forces will need this practice, and all must be able to work at night if they are to be of full value to the country. Timed marches, allowing for halts and beginning with a start from a bivouac in which the troops collect their belongings and become accustomed to moving out of halting places in an orderly and quiet manner; employing cross tracks and instructing troops to recognise them by landmarks and features at night; small marches by different parties to meet at a certain hour at a given place; the withdrawal of outposts in the dark for it night movement; these, and many other situations which thought will readily suggest are valuable methods accustoming troops to work at night. This can well be applied to Citizen Forces, and will give good results.

Secrecy must be maintained, as if any news of a projected night movement reaches the enemy, he is at once in possession of a means of dealing an unexpected and disastrous blow, for the force which awaits another, prepared to surprise and attack it at night, has its objective at a tremendous disadvantage.

How to maintain secrecy, and yet insure the general knowledge to which I have referred as necessary for individuals to possess, is always a matter of difficulty. Confidential verbal orders to commanders of units before starting, and arrangements which will enable them to instruct their subordinates at the first halt after the night march has begun will be the safest plan when the size of the force allows it to be adopted. Camps and bivouacs should be prepared for the night in the usual way, and any action which will tend to indicate a movement from them, or the fact that something unusual is contemplated, should be avoided as far as is possible. Secrecy is absolutely necessary if success is to be assured, and when, as will be the case in war, knowledge of the intentions of the commander of the force is eagerly sought after by an enterprising enemy, it is extremely difficult to keep from that enemy the intention of a night movement. A force in which the vast importance of secrecy is generally taught and known, and which by practice has become easy to handle by night, will be best able to conduct night movements. Every effort should be made to give the impression that no movement is contemplated, and, when the troops are sufficiently trained, a movement in a direction opposite to that which leads to the objective and a rapid change towards the latter after the march has begun, will often prove effective. Well-trained troops, and a careful calculation of time, will always be necessary if such a ruse is attempted. Secrecy during the movement must be secured by forbidding all talking, and striking of lights and by strict injunctions that fire will not be opened without orders from superior authority-who should be defined in each case. The officers who have the right to order fire should, if possible, be made known, in order that unauthorized fire may not be delivered, and that only those who have the right to give the order shall do so.

The action of the force in case of surprise should be arranged for, and communicated as far as is necessary for its adoption. Disciplined troops who have been instructed to take a definite line in a given emergency will take it, and in the absence of knowledge in the above respect any troops will be specially liable to panic. Instances of want of foresight in this respect and its result will no doubt occur to many readers.

The order of march is an important point in a mixed force (that is, containing units of more than one arm). Where a column contains infantry, the usual protective guards will be furnished by that arm; mounted troops and artillery will march in rear of the bulk of the infantry. Where the route has been well reconnoitred or is well known, a few carefully chosen mounted patrols under an officer who has reconnoitred or knows the road thoroughly may be sent ahead to occupy good positions which will command it, and which, if held, will deny the advance. The knowledge that the road is clear for several miles ahead is valuable and reassuring to the commander, and may materially aid him. Unless, however, the points which should be aimed at by such patrols are well known by those concerned with their supervision, extended patrols of this nature may easily become a source of danger, especially if the enemy allows them to go through.

All places passed en route, from which inhabitants may reach the enemy with information, should be secured by mounted detachments of such strength as may be necessary, who will guarantee that all inmates remain on the spot until the need for concealment has ceased. These detachments should be pushed on sufficiently far ahead of the force to prevent the escape of any person before the column arrives and, if the inhabitants cannot be conveniently taken with the force, must remain until the possibility of information reaching the enemy no longer exists.

At daybreak the order of march will, if the movement continues, be changed to that usually adopted in the daytime, and the mounted troops will assume their duties of protection. The abortive night march to Stormberg again is an instance of the failure to readjust the formation of a column on the march at daybreak.

Night Combats -

Combats at night entail certain disadvantages to the attacking force when the enemy is in position. Of these the most important are:

1. Liability to panic in the event of an unexpected development. The sense of being at the mercy of the foe who is waiting for you, the feeling of insecurity and helplessness, which is the result of not seeing the situation plainly, and the different appearance of objects familiar by day, all contribute to an exaggerated sense of danger.

2. Extreme difficulty of supervision. Darkness prevents the supervision possible by day, and lack of supervision and control mean opportunities for shirking - men are easily lost in the dark - and an inability to keep your whole strength available.

3. I have refrained from touching on native warfare, but I must mention the fact, when reflecting upon the possible employment of South African troops, that to fight in the dark against. natives is to neutralize the effect of superiority in arms of precision, and to give the advantage to the superior numbers of the enemy, who are far better able to fight hand to hand in the dark than white men.

In defence, fighting at night is due to the force of circumstances, and is more or less involuntary. Every position taken up by any body of troop on active service at night should be carefully reconnoitred and occupied, with the object of offering the most determined and effective resistance possible. No matter how improbable an attack may seem, there is no justification for any commander who neglects to make the fullest preparation against surprise at night, or early dawn. Almost every night attack which succeeds does so as much from the lack of precaution on the part of those attacked, as from the skill and determination of the attackers. Outpost work is trying, and a weak commander may be prevailed upon to take the opportunity of what seems to be a very small probability of attack to relax precautions, which should never be done while an enemy is in the field.

As far as night combats are concerned, I will confine myself to the discussion of two kinds of combat. I do not propose to consider night attacks on a large scale, but merely to refer shortly to combats of a nature which makes it very likely that mounted riflemen will be engaged in them. They may be classified as (1) enterprises deliberately planned and on a small scale, and (2) encounter combats.

Their mobility, and their experience of such combats while moving au night, increase the probability of their employment upon such enterprises. Small offensive undertakings, such as the sorties at Ladysmith against Gun Hill and Surprise Hill, are useful to harass an investing force, and inspirit a force which is invested. Mounted riflemen who are able to reach and retire from any spot rapidly are useful for such work. The seizure of advanced and commanding positions in darkness, to aid the development of a general attack at dawn, is a task which may also be well allotted to the arm.

Comparatively small forces will be required for such missions, and the following points demand careful attention:

1. Previous reconnaissance or thorough knowledge of the ground is essential. Groenkop, cited in the last chapter, is an admirable case in point.

2. The attack must be a surprise. If it can be launched from the direction which seems the least likely for the purpose, so much the better.

3. Troops on whom implicit reliance is to be placed are alone suitable for such work. The personnel for any enterprise of this nature should be carefully chosen. The process of elimination by which Gideon obtained his men is interesting to follow. Good leading is of vast importance; good troops are indispensable.

4. A whole-hearted offensive is essential. Grave risk must be taken, and there must be no hesitation.

5. The operation must be carried out as noiselessly as possible. Here I wish to make my final reference to the bayonet, as calculated to be of immense value in tasks which demand the taking of life at close quarters when it should be done without noise.

6. If a position has been taken at night and is to be retained, it should be entrenched with the least possible delay after it has been thoroughly reconnoitred. Majuba and Spion Kop are striking instances of the evil of an inadequate reconnaissance and too ready acceptance of a position taken up in the darkness. Nothing done at night should in such circumstances be regarded as final, the troops should be kept ready and alert all night, and early dawn should see another reconnaissance of the position to decide if anything is necessary in the way of alteration in the dispositions.

In encounter combats at night, success will, in the majority of cases, attend that force which, taking advantage of the mutual surprise, adopts at once and maintains the initiative by a vigorous offensive. The promptitude of the leaders, and the excellence of the troops, will enable any force which acts at once and sustains an offensive attitude, accepting the whole risk, to defeat a far larger body of an enemy which hesitates in the first moments of surprise.

To sum up, night movements will be resorted to constantly, especially to bring forces unexpectedly to a scene of battle at dawn. Night attacks in South African conditions of warfare as a rule will be undertaken sparingly on a large scale, but in the way of small enterprises will be an effective form of action. Night training is therefore essential.

Previous: Part 6, Protection

Next: Part 8, Reconnaissance

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Militia and AIF, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 7, Night Operations