Topic: AIF - Lighthorse

The Australian Light Horse,

Militia and AIF

Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 8, Reconnaissance

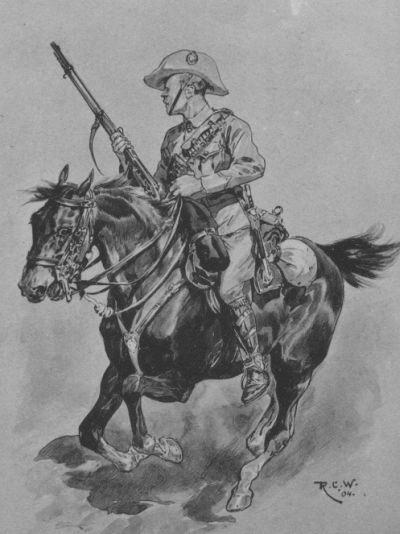

Cape Mounted Rifleman

[Drawing from 1904 by Richard Caton Woodville, 1856 - 1927.]

The following series is from an article called Mounted Rifle Tactics written in 1914 by a former regimental commander of the Cape Mounted Riflemen, Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Collyer. His practical experience of active service within a mounted rifles formation gives strength to the theoretical work on this subject. It was the operation of the Cape Mounted Riflemen within South Africa that formed the inspiration for the theoretical foundations of the Australian Light Horse, and was especially influential in Victoria where it formed the cornerstone of mounted doctrine.

Collyer, JJ, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Military Journal, April, 1915, pp. 265 - 305:

Mounted Rifle Tactics.

VI - RECONNAISSANCE.

Importance - Information - Scouting - Specialization - Intelligence units -Instructions necessary - Reconnoitring patrols - Reports - Patrol leaders - Reconnaissance for attack - For defence - Roads - Conclusion.

In previous chapters I have constantly referred to reconnaissance as especially the duty of mounted troops. Frederick the Great says:

"If one could always be acquainted beforehand with the enemy's designs, one would always beat him with an inferior force."

It is hardly necessary to draw the attention of those who have fought in South Africa to the enormous advantage possessed by a military force which is thoroughly at home in the scene of fighting, knows every yard of country, and speaks every language required for conversation with those best able to give information. If this great advantage is rightly appreciated, it is a simple matter to imagine the corresponding disadvantage under which a force labours when it operates in a comparatively unknown country, and is ignorant of its customs, languages, features, and even climatic conditions.

It will be allowed that the value of information in war is inestimable, and, if the history of campaigns is studied, we find that great commanders have often provided themselves with a select body of men, carefully chose for special qualifications, to collect information in the presence of the enemy, a duty which, shortly stated is reconnaissance. These special bodies may be regarded as intelligence units, and have proved invaluable to those who have employed them. That such care has been taken to select these men, and that such importance is attached to their work, plainly proves that, for the purposes of reconnaissance, military attainments beyond the ordinary and special qualifications are required.

Scouting must not be confused with reconnaissance, for scouting is only a part of the duties demanded by reconnaissance work. My reason for alluding to scouting is that I think there is a danger of regarding the duty of scouting as that allotted to certain picked men of the mounted troops, and not the concern of the ordinary man in the ranks. My opinion is that scouting should be taught in every mounted regiment and that every mounted rifleman should be a scout. The special nature of reconnaissance demands that officers and non-commissioned officers of mounted units should be thoroughly conversant with the duties of the conduct of reconnaissances, and the leading of reconnoitring patrols, and that every man who is liable to find himself employed in the ranks of such patrols, that is to say every mounted rifleman, should be well posted in the methods and practice of scouting. The specially selected personnel of the intelligence units to which I have referred should be employed by the commander of a force on independent missions which call for the use of highly qualified individuals, and should be at the disposal of the commander for intelligence work only, or for tasks which are of an important or, may be, specially confidential nature.

The specialized system of scouts which is the method adopted in the Imperial Army, and is no doubt suited, in the opinion of those best able to judge, to that army, should not be followed in the mounted rifle regiments of South Africa, in which general proficiency in scouting should be demanded just as much as, say, general horsemanship and marksmanship. The very nature of scouting demands constant risk and exposure to injury at the hands of the enemy, and if it is the custom to allot this duty to a few specialists, casualties will thin their number very rapidly, and mounted rifle units will then have to extemporize their scouting arrangements in the field, with the usual disastrous consequences attending such hurried action.

In the case of intelligence units, the personnel will be carefully chosen and probably well paid; for, apart from their scouting ability, they must have better general military knowledge than is possessed by the ordinary man in the ranks; with mounted rifle units the risk to be undertaken should be spread equally throughout the regiment, and efficiency alone demands that every man should be able to undertake duties of exploration in advance of the main body.

I would advocate the formation of intelligence units to be composed of men specially chosen for the work-say, thirty to fifty strong-and available for general intelligence work in war, and for distribution as required. While possessing special knowledge of their own district, these men should receive a training of a; nature calculated to improve their natural capacity for reconnaissance work.

The importance of reconnaissance is denied by no one; its extreme difficulty and the necessity for special qualifications in those who conduct it are even now too little realized. Frederick the Great required a higher standard of general military information from his cavalry officers than from his infantry officers of the same, rank, thus recognising the fact that the better educated in a military sense his reconnoitring officers were, the more probable it would be that he would get good results from their efforts.

Reconnaissances may be undertaken to acquire information of every kind, but I propose to consider specially reconnaissances of an enemy as the form of reconnaissance which will generally fall to the lot of mounted riflemen. In "The Duties of the General Staff," the following appears:

"It may he laid down at once as a principle to be strictly followed, that whereas everything that in any way bears on the military situation at the moment must be most carefully examined; all that does not apply to the questions wider consideration should be as pointedly avoided."

Full instructions therefore must be given by those who are in a position to issue them to all leaders of reconnoitring troops as to the situation, and with reference to the nature of information which it is desired they should procure. If reconnoitring patrols know clearly the nature of information which is wanted, and the state of affairs which exists, and are allotted definite directions in which to work, there will be no duplication of work or loss of time, and the very trying duty will be performed with the least possible friction. This will be the duty of the authority who sends the patrols out, but every patrol leader should be in possession of this information before he leaves on his task.

The strength of reconnoitring patrols must be decided in view of the situation, the duration of their mission, and the distance which they will be compelled to travel. They must be as small as possible, to lessen the chances of detection, and they must be strong enough to obtain information, send it back, and protect themselves whilst keeping in touch with the enemy. At night, especially when sent out to watch the enemy and report his movements, the patrols may be made stronger, as they are less easily discovered, and may have to extricate themselves at daybreak.

How to protect his patrol, and retain enough men to carry on the work, and yet send back all the information which he may collect, is the problem which confronts the patrol leader during the whole time of his absence from his main body. Good tactical knowledge of his own arm to enable him to use his patrol to the best advantage, and sound general military judgment to decide the value of the various items of information which he gathers, are absolutely necessary if the leader of a reconnoitring patrol is to do good work. The system of transmitting reports must be arranged before leaving, and any proposed means other than employing men from the patrol must be known and furnished.

A summary of the situation should be given to the patrol leaders, and, when what is wanted has been made clear to them, they should be allowed freedom of action in carrying out their work. It cannot be too well realized that, once a patrol has started on a mission of reconnaissance, the value of its work will depend entirely on the ability with which it is handled. The information which comes back from it will form, with other reports, the basis of arrangements which the commander will make, and will involve the success and safety of the whole force. Mere scouting, however well it may be done, and the good tactical handling of the patrol, will achieve nothing unless definite information of the nature required is obtained, and from the varied details of intelligence which a patrol may collect, the useful must be separated from the non-essential, and the more important from that which -in the circumstances is less valuable. In short, a careful estimate of the value of the information, in view of the situation which may at any moment assume an aspect entirely different from that which existed when he received his instructions, must constantly be made by the patrol commander, who will have nothing but his own ability and military knowledge to rely on.

Points which a patrol leader should bear in mind are:

1. That while he will have been instructed to procure definite information, he should endeavour when carrying out his special orders to collect intelligence of every kind. The situation may change, and what may have been passed by as unimportant may become suddenly of considerable value.

2. That all the men of the patrol should know enough of the situation to enable them to continue the work if the patrol suffers any loss, and to assist them in gathering information.

3. That touch with the enemy, once established, should never be relinquished till the authority who sent out the patrol orders its return, after knowing the situation.

4. That all important information should be sent by more than one route, and carried by more than one individual, if it is not perfectly clear that it must reach its destination.

5. That negative information (e.g., that the enemy was not in a certain place at a certain time) is of value.

6. That the “most perfect reconnaissance is valueless if its result is not known at the right time."

7. That in order to obtain good results he must constantly estimate the value of the information which he receives in the light of its probable value to the commander who is expecting it, or, in other words, must in imagination put himself in that commander's position.

8. All men sent back with messages should be made to repeat them before leaving till they can do so correctly, and the habit of framing reports mentally before delivering them should be cultivated by all those, of whatever rank they may be, who are likely to have to make them. A verbal report made quietly and clearly, it may be at a moment when everything tends to excitement, is sufficiently rare and useful to call for practice in what seems, in ordinary circumstances, a simple enough proceeding. Practice will give very good results.

The conduct of reconnoitring patrols, as far as their protection is concerned, resolves itself into a skilful and bold tactical handling of small parties of mounted riflemen, which I have discussed already elsewhere. Good reconnaissance cannot be performed unless the troops engaged on it are used with judgment, but vigorously and confidently.

I will now shortly consider some special forms of reconnaissance.

Emphasis must be laid on the fact that no rule of thumb is possible in reconnaissance. The information which should be obtained is that which is required by the commander for his special purpose, whether the intention is an attack, or defence, or an advance or retreat, or whatever it may be. If, however, troops are to be trained in peace some general outline is necessary, and the following points are put forward as those upon which information would generally be required in the circumstances assumed.

Reconnaissance for Attack -

Two usual types of reconnaissance for attack present themselves. Reconnaissance of

1. Ground which we hold, but may have to abandon;

2. Ground in the possession of the enemy.

In the first case, the force may fall back and attack on being reinforced, or an advanced guard may be compelled to fall back in view of an attack to be delivered when the main body is reached. The possibility of such a situation emphasizes the necessity for good reconnaissance by advanced guards. The main points in either case, on which information will probably be necessary, are:

1. The extent of the position. This may be an extremely difficult point to determine, and will be best decided by an endeavour to locate the flanks, supplemented by a careful study of the position, with the object of making up one's mind as to how one would defend it, and attributing what appears to be the soundest line of action to the enemy.

2. Any weak spots in the position, such as a salient, or any position which can be dominated by fire from a position which may have been left unoccupied by the enemy.

3. Positions which, in the possession of one's own troops, would afford opportunity for obtaining superiority of fire or for delivering reverse or enfilade fire.

4. Where counter-attack may be looked for. The defence will be contemplating the delivery of a counter-attack, and if it can be anticipated his main effort will be seriously affected.

5. Careful attention to the ground to be crossed in advance. Rallying points, such as kraals and features affording good cover from view and fire. Suitable ground for the advance from cover to cover.

6. All obstacles and the best way of avoiding them; wire fences or deep dongas, for example.

7. The extent of ground to be occupied by the different units. This is more or less important as the force is comparatively large or small.

8. Facilities for intercommunication. If an attack is to be delivered with its full weight, and a counter-attack is to be warded off, the rapid communication of intelligence and orders is necessary.

9. A good position for the commander of the force and his headquarters. A good suggestion as to a central position from which a general view is possible may be of the utmost value to a commander coming up hastily it may be, from the rear.

10. Careful observations of all dead ground in front of the position. The observation of ground held by an enemy needs practice, and an opinion formed from a distance often needs much modification on closer inspection.

11. In all reconnaissance work no report should ever be made that anything is the case unless it is known that it is so. Unverified information should always be qualified, but when it seems likely to be of value should be sent in as unverified, for the corroboration may have been furnished by other parties.

Reconnaissance for Defence -

Reconnaissance for defence will perhaps often be undertaken more or less deliberately, and will not concern mounted riflemen to the extent that attack and route reconnaissances will be performed by them. In the defence, however, mounted riflemen, as we have seen, will be used freely in conjunction with other troops, and some points as to defence reconnaissance may be useful.

Defence reconnaissance has two main advantages as compared with the usual form of attack reconnaissance, viz.:

1. Availability of the ground;

2. Possibility of greater deliberation.

Defences of positions again group themselves naturally into defence for a given time for delaying action, and defence of the kind which looks to win a fight in the end. The main difference which influences reconnaissance is that in the first case, provided the defence is assured for the given time necessary, the enemy may be allowed to make points and take up positions which could not be allowed to him in the second instance.

Reconnaissance in connexion with delaying action means really a matter of calculation as to how long a given tactical situation will take to reach a given phase. For a defensive fight, which contemplates a counter-attack, the best arrangements possible must be made for a more or less indefinite period.

The following points merit attention:

1. The position should be the best for the purpose. An ideal position is rarely met with in defence. It is as a rule dictated by necessity, as the initiative is with the enemy. A good field of fire and secure flanks are important essentials.

2. Obstacles which may aid the defence and impede the advance. Obstacles are specially useful in dealing with natives.

3. One main position should be accepted, and, at night especially, a clear idea as to what constitutes this main position is essential.

4. The position from the point of view of the attacker; the enemy's point of view should always be considered. Omission to consider the hostile view-point leads often to what is one of the most fatal of errors, a preconceived notion of the enemy's action.

5. The routes for any probable movements laterally, or to the front, or to retire if necessary.

6. Signalling facilities and communication throughout the position.

7. As in attack, the careful selection of a place suitable for the commander of the force. As the consequences of defeat are far more serious as a rule than in attack, good control and supervision become even more important.

8. Positions for reserves and routes to the probable scene of their employment. This will include measures for counter-attack.

9. Positions which can be used by the enemy to the detriment of the defence.

Tactical Road Reconnaissance -

I do not propose to examine non-tactical reconnaissances of routes, that is when action by the enemy is not to be considered, but to enumerate one or two points in connection with which information may at any time be needed from patrols of mounted riflemen.

1. If transport is to be considered, the route must be examined with reference to the method of movement of the vehicles. In some countries it is possible to move with ox-waggons abreast, and so reduce the depth of the column.

2. All obstacles and defiles must be noted, as they mean loss of time in passing them, and the rate of march is influenced by them. Any way of improving them should be observed.

3. The nature of the ground on each side of the route, whether close, hilly, and wooded, or open and flat, whether cut up by dongas or available for free movement on a large front.

4. Roads or tracks crossing the route to be followed.

5. Positions where attack or opposition may be expected, and how these may be made good.

6. Positions for halts which are convenient for protection and comfort.

7. Never state a difficulty or obstruction unless it exists, and always observe how it can be surmounted, or state that it cannot be overcome.

The above are only some of the problems which patrols of mounted riflemen may have to consider. They are enough to show at least that a good standard of general military knowledge must be possessed by those who would solve them.

Previous: Part 7, Night Operations

Next: Part 9, Conclusion

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Militia and AIF, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 8, Reconnaissance