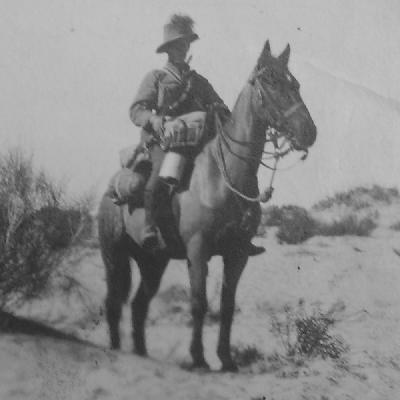

Prior to that Priestley served in South Africa 1901-2 with the 5th South Australian Imperial Bushmen in Cape Colony and Orange River Colony and was awarded the Queen's South African Medal with four clasps. During the inter war years he served with the South Australian Mounted Rifles 1900 - 1910 when he was placed on the unattached list. At the outbreak of the Great War, he enlisted with the 3rd Light Horse Regiment and embarked with "A" Squadron. He was Killed in Action on 3 May 1918.

The following is a 3 part series of this article. A fourth part was attached as his article was critiqued by Major F. A. Dove, D.S.O., A. and I. Staff, in the

, May 1912. Both articles give valuable insights in the basic thinking around the use of Light Horse scouts, detailing both theoretical ideas peppered with experience wrung from the recent war in South Africa.

Light Horse Duties in the Field

Scouting.

(2) The Scouts of the Screen.

Since scouting is a duty of every day, scouts will usually be detailed fro," their troops by roster. It follows, however, that unless precautions are taken the scouting will vary according as the roster details the best men grouped in one or two sections or the worst grouped similarly. The precaution against this is to insist that each N.C.O. who is a section leader must be a good scout, so that his section is capable of good work though it may include indifferent men as well. Then if in the syllabus of competition for section leadership to lead the remaining sections of the troop the element of scouting largely prevails, it will follow that, each section is commanded by a good scout. Moreover, since this system selects the good scouts and divides them amongst the several sections as leaders, it follows that the indifferent scouts are also divided, and the scouting ability of the sections is approximately uniform.

Scouts in front of a troop ride with an interval of about a hundred or more yards between files.

A good scout will never waste time during the ascent of a rise he will let nothing attract his attention till he is on its summit.

When approaching a hill a scout should always select what part of it seems to offer the easiest ascent, and direct his path to it from a distance. Scouts ought not to ride in anything like a straight line, but as Lang as they are observing the whole of the ground allotted to them they should vary a hundred yards or so to either side, it does not matter if two are thus brought close together, it prevents a hidden enemy from forming any opinion as to whether or not a scout is likely to miss seeing him. Following an irregular line or path it is impossible, to say with any certainty which part of the hill he is about to cross.

The section should open out so that each scout ascends by a different path. It is not a matter of concern if they should lose sight of one another in doing so, as long as each is under the troop leader's eye.

When the hill is steep and rocky, so that it affords plenty of cover, the scouts may expect to draw fire, but may remember that such a hill has usually cover for them also if they need it. If the hill is precipitous a scout may know that it is almost impossible to fire straight downwards with anything like accuracy, and should consequently get as close to the cliffs as possible. Even on bare hills some cover may be expected. The minor watercourses are rarely so regular that they afford no protected approach to near the summit. Then again there is the dead ground of the contour. Every convexly sloped hill yields cover from its base to some distance up, and on concave slopes, dead ground may sometimes N' found near the summit. Usually the heads of minor watercourses provide dead ground near their origin, and consequently close to the summit of the hill.

A scout when doing duty with a picquet should notice the form of ground that is most easily watched, and note the minor features which need special attention. He will find that the general run of hills are convex, and that there are numerous minor watercourses running upwards that are entirely disregarded by a picquet on the crest, and there is the dead ground at the base. The picquet watches the opposite hill and the entrance to the dead ground between, but when once a scout has crossed to this dead ground he is lost sight of, and may approach unseen. This disappearance of scouts is very provocative of premature firing. The scouts being lost sight of there is no way of knowing where next they will appear, and their troop will be approaching over the skyline behind them. It is very unusual for fire to be reserved under such a combination of circumstances.

Scouts ascending a hill should make their objective that part of its crest which presents the lowest skyline. By doing this they so much the sooner see what is beyond it, as there is less climbing, they can expect to find that part at least unoccupied, as picquets usually hold the highest knolls, and their course to the toll or saddle leads them in the neighbourhood of the minor watercourses and the cover they afford, and moreover the approach to the skyline is less conspicuous at a distance as it will be under cover of the higher ground on both flanks.

The course of a scout up a minor watercourse of a hill leads him naturally to a saddle if one is present, and takes the fullest advantage of dead ground, even possibly between two picquet posts if they are at all badly situated with regard to convex slopes. No scout should ever ride up the spur to the highest point of a ridge or hill. The knolls and commanding positions are only to be attempted by scouts after inspection of the ground beyond.

A scout must always avoid showing himself over a skyline until he has seen beyond it himself. It is the only way to effect a surprise in the daytime. A useful hint to remember is this, that while he can see nothing over it, nothing can see him, and when he can just see an object the top of his head will be only visible. If he has seen something of importance while thus approaching a skyline, he can signal to his troop leader. It is beyond the duty of scouts in the screen to estimate the importance of what they see that there may be something unusual is all that concerns them. This may be illustrated by supposing that a scout can just see over the skyline a portion of a horse with a saddle on. That is why he signals to his troop leader; he would be exceeding his duty if he made any attempt to see anything further. A scout alone can do very little but see, and the duty of the troop leader is to gain information at first hand, not to commence an elaborate attack on a hill because his scouts can see something beyond it. So too it must be if a scout sees waggons or a gun crossing a distant skyline.

Once having seen the country over the skyline, the concealment of a scout becomes of less importance as the advance guard, supports, and the whole column will soon be crossing it. Then it is that the scouts of a troop may attend to the knolls and scan what is before them from the more commanding points. It is then that the men who compose the scouting section may close in and speak between themselves of the work done and to be done. There they may remain if the aspect is extensive till the troop leader reaches them, and receive his comments or instructions. This halting of scouts on commanding positions is very useful, as it assists in maintaining a closer touch between the scouts and the troop, and it gives the troop leader a greater control of the scouting.

As a rule scouts should avoid remaining in one place, but rather should be always on the move. Their work is not to hold a position, it is to see. It is very seldom that a knoll is such that a section of scouts grouped together can see everything around it from one spot. It is only by a habit of being always on the alert that a man will become a scout. Each movement will afford some difference in the field of view, and as a rule positions that command an appreciable space of country are rare. A scout who rides up to a skyline, and showing himself at once waits on the same spot till ho may proceed, is not doing his duty. He would probably be limiting his view to half* of what may have been possible to him. Moreover such a scout is one that an enemy would wait for. A scout when he has shown himself, and at the same time shown himself to be smart and alert, rives a watching enemy the impression that no good can ensue from waiting for him.

A scout will never ride over a skyline till his troop is at least ascending the hill he is on. This must on no account be varied. Scouts are of use only as long as they are seen, if out of sight they are out of touch. Once out of sight a scout may be ambushed and captured, while his troop follows him into the trap. Unless this is absolutely adhered to, each skyline as it is encountered presents the opportunity for an ambush, since each body in turn can be caught as it crosses and becomes out of touch with its support.

The ground between ridges should be rather hurried over, especially the descent, so that time is afforded the scouts to work the skylines properly. If waiting on a crest till the troop leader arrives, they recommence their advance at a gentle canter, there is no better way of varying the steady walk that is the usual pace of the column.

On the whole, scouts should move somewhat faster than their troops, on account of the greater extent off ground they have to cover. They should habitually adopt a rather haphazard direction in preference to riding straight on their objective. The best scouts when working appear to be wandering in an aimless manner from one hill to another, and yet remain approximately in front of their troops. Each seems to turn to his right or left as his fancy takes him, but he is examining all points of the ground. The scout who rides from point to point indicates his path for some distance ahead. Hoe will prove effective in drawing fire as the temptation to wait for him is usually too great.

A very useful pace for a scout is a jig-jog trot. A horse accustomed to this pace covers an enormous amount of country with little fatigue, and by changing it to a walk in ascending a hill the horse experiences a certain relief to counteract the uphill work. Moreover, a horse that is accustomed to this pace in screening work is less fatigued by the monotony of long marches in the main body at the one pace. Horses that are fast walkers or that amble are very useful, but others soon learn the jig-jog, and the movement becomes an easy one from use to both the horse and rider. What is known as the pace or triple, is also an excellent accomplishment for a scout's horse. These remarks do not, of course, apply to the trained horses of regular regiments.

When scouts encounter an isolated hill or the end of a prominent spur run ring across their path, they do not want to ride over it as much as to see what is beyond it. This is best done by certain of the party riding around it while the others deal with it in the usual way. Often a certain amount f co-operation between the scouts of two or more troops can be used in such a case as this.

Scouts must be continually on the alert for any change of direction on the part of their troops, and will frequently look back to observe such as soon as it occurs. Apart from the general question of touch, by making minor changes of direction which do not affect the general line taken a troop leader can indicate to his scouts what ground he wishes them to scout or avoid.

It may not infrequently occur that an almost precipitous hill lies at a distance to the flank of the route of march, so that rifle fire from it would reach the column at long range, and yet the location of the hill and difficulty attending its ascent seem to put it rather beyond the scope of the flank troops of the advance guard. In this case it will be a flank guard position, and does not need the attention of the advance guard. If the latter were to deal with it so much time would be expended that in all likelihood the column would be passing it with an opening in the screen caused by the delay of this troop of the advance guard.

The correct way to deal with it from the point of view of a flank troop of the advance guard is to avoid it by closing in to the centre troop so as to be under only long range fire from it. The scouts should seek protection of its cliffs by going close to it. They may in this way draw fire from it, but a downward fire from the summit would be of little consequence, while useful information in regard to its occupation may be obtained for the flank guard.

It sometimes happens that the flanking troop or scouts of an advance guard are working along the crest of a ridge that runs, almost parallel with the line of march and then curves away so as to become beyond the scope of the screen. In this case the scouts are apt to leave the ridge in a slanting direction parallel with the line of march By doing this they move for some distance under an unoccupied skyline, which is bad. The correct line for the scouts to work on would be to follow the crest of the hill for some distance further outside, and then leave it by galloping in a slanting direction in towards the column, but square with the crest of the ridge. In this way the scouts get clear of the ridge' at once on leaving it.

In ascending a ridge of similar nature that curves in towards the line of march the same plan should he followed. The scouts should turn outwards from the column so as to encounter it squarely, and will resume their interval with the column as the ridge approaches its line of march.

A scout should always bear in mind that the curve of trajectory affords safety, and that an enemy will as a rule never fire at a single man while there are larger targets available. Knowledge of those two points will often enable a scout to move confidently even under fire. The case especially occurs when some dead ground is covered from hostile rifle fire beyond it, and there is need to see if it is unoccupied or otherwise.

A valuable hint to a scout is that there is nothing more puzzling to an enemy who is watching him than to use his cover (that of the enemy) for concealment.

When a scout is using dead ground below the crest of a convex hill he is doing this, and the principle can be extended so that a scout expecting that he is being watched by an enemy behind an isolated knoll or patch of timber or a house may, by avoiding to show himself to that side of the cover which he believes to be occupied by the watching enemy, know that he is moving in dead ground.

Whenever the main body of the column halts the scouts will remain on the ground they occupy in front of the screening troops as observation posts, but if they happen to be with the troop on a commanding position there is no occasion for them to push out till shortly before the column resumes its march. Should the halt be for the purpose of camp, the scouts or observation posts will be recalled unless the local conditions at the time need an observation post in front of the picquet line of the camp. The object of this is to prevent the necessity of the scouts having to re-occupy any points they have previously abandoned, when the column moves on. If the scouts of the enemy see the post retiring, they are certain to occupy it at once in the search for information, and from this cause the re-occupation of an abandoned post is always uncertain work. This applies to the scouts of the advance and flank guards only, as the scouts or pointers of the rear guard do not hold their ground, but fall back on their troop. In the latter case a movement on the part of the column may not be expected to entail the reoccupation of the ground vacated.

The case of an attack being developed against a column which first opens against the scouts is worthy of attention. The scouting sections analogous to the observation posts of a picquet line are beyond the line of resistance, but unlike them are connected with a support which is mounted and ready for instant use. From this latter it occurs that the action of observation posts and scouting sections differ when attacked. With the former the supports, in addition to the picquet which must not move off its post and so is not available for the purpose, are at least dismounted and in camp. The time that would be needed to mount a force and move it to support a weak post in advance of the picquet line would afford the enemy such an interval that they could overcome the observation post if it waited for the purpose. Hence observation posts will retire on to the picquet line as being the line of resistance, and there assist the picquet to hold the ground till reinforcements arrive.

On the other hand with scouting sections the support necessary to push out beyond the line of resistance is available at an instant's notice, and local conditions should decide whether the scouts are to retire or to be supported by their troops. The control of the matter is however, under the troop leader. Scouts are allowed to dismount and fire only on condition that they are situated on an excellent commanding position and their firing is a signal to the troop leader that the position they occupy affords a field of fire on the enemy. It remains with the troop leader to use it or not. If he decides to use it he must move towards it as soon as he sees his own movement is supported, or will entail no loss of touch, so that the scouts can be made aware of his purpose. If, on the contrary, he will not go out to it, then his continuing the regular guard work will indicate to the scouts by his disregarding their action that they are to cease fire.

The latter case of a troop leader declining to move out to the ground the scouts hold applies to flank guards, especially because it is their duty to maintain a defence along the line of resistance parallel with the line of march. With this guard it is the exceptional case for a troop to move out beyond the screen, and is only to be done when the troop leader sees his squadron leader bringing up the supporting troop towards him, and if the position is obviously a simple one, that does not entail by its occupation the occupation of other ground in addition.

With the advance guard there is less option, but even though the principle of the work of this guard is to press on, some caution must be exercised. As a rule, whenever the scouts of an advance guard open fire their troops will push up to develop a firing line on the ground they hold, but even this must only be done while the troops continue in touch with their supports. If the troop leaders persistently follow their scouts every time they open fire, they will be apt to get so far ahead of their supports that the advance guard may be cut off, and thus afford the opportunity of that form of attack which is one of the most likely to be disastrous to a mounted column, the delivery of a surprise attack between the advance and flank guards on the guns and troops of the main body in column of route.

In the case of an attack on the scouts or pointers of the rear guard, there is to be no attempt made to hold a position; the scouts must retire.

The rule for scouts holding their ground when attacked becomes this, that they never attempt to do it unless supports are pushed out immediately on their opening fire. Beyond the instance of inferiority of numbers there is only one exception to this rule, and that occurs with the flank scouts of the flank troops of the rear guard. These, if well situated in respect to the rear troops of the flank guard, and in such touch with their troop that they become an extension of its firing line to that flank, will hold their ground. Their real duty is, however, not so much to increase the strength of the rifle fire, as to maintain a watch over movements of the enemy, so as to have early information of any attempt on his part to enfilade the firing line that the troop has established.