Topic: AIF - Lighthorse

The Australian Light Horse,

Militia and AIF

Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 6, Protection

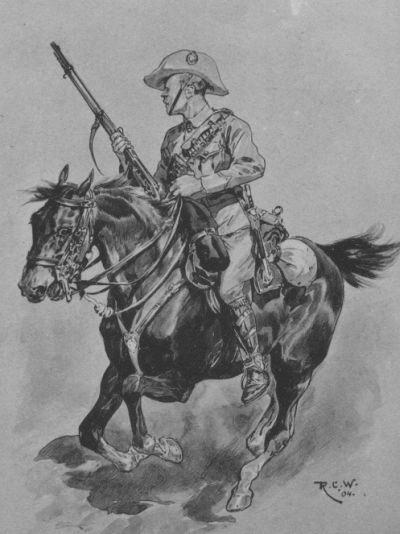

Cape Mounted Rifleman

[Drawing from 1904 by Richard Caton Woodville, 1856 - 1927.]

The following series is from an article called Mounted Rifle Tactics written in 1914 by a former regimental commander of the Cape Mounted Riflemen, Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Collyer. His practical experience of active service within a mounted rifles formation gives strength to the theoretical work on this subject. It was the operation of the Cape Mounted Riflemen within South Africa that formed the inspiration for the theoretical foundations of the Australian Light Horse, and was especially influential in Victoria where it formed the cornerstone of mounted doctrine.

Collyer, JJ, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Military Journal, April, 1915, pp. 265 - 305:

Mounted Rifle Tactics.

IV - PROTECTION.

Definition - On the march - Advanced guards - Rear guards - In action - Halted -Reconnoitring patrols - Groenkop, 1901 - Standing patrols - Moving protective patrols. Safety of patrols.

"Every commander is responsible for the protection of his command against surprise." (Field Service Regulations.) Surprise, the most valuable aid to all military operations, and employed by every great military captain to the fullest extent, is aimed at by a good commander to enhance the value of his action against the enemy, and is anticipated by him, and guarded against, so that his adversary's attacks may not find him unprepared.

"Protection" is the name given to the measures which a commander adopts to save his force from surprise at the hands of his opponent. This protection is necessary on the march, in action, and when halted, when forces are employed on service against an enemy. We may perhaps best discuss protection under the conditions stated above.

It may at once be stated that the most satisfactory, and safest, protection that a commander can insure for his troops, in any circumstances, is that which is procured by a full knowledge of the whereabouts, strength, and movement of the enemy. In fact, as Field Service Regulations assert, "If an enemy is so continuously watched that he can make no movement without being observed, surprise will be impossible."

I do not propose to deal with the composition or formation of the various bodies designed to undertake the duty of protection-such details are contained in training manuals-but to confine myself to a discussion of certain principles connected with their employment.

Protection on the March -

Protection by day on the march will be the duty of the mounted troops, whose mobility and power of covering long distances enable them to do such work. The duty is arduous, calculated to impose much strain on those occupied with it, and physically exhausting to man and beast. I think it well to mention what may perhaps seem too Obvious to call for reference, for although the horse soldier is well aware of what is involved by the demands which are made from him and his mount on such work, those who do not belong to a mounted arm are often inclined to overlook the amount of energy which has been expended by the mounted troops, especially when the question of protection when halted has to be faced. This I will consider in its proper place, but it is well to insist that in the matter of protection each arm should do its share in the circumstances which suit it best, and that no effort should be spared to maintain the mobility of the mounted troops by employing the infantry whenever conditions are such that they can do their portion. By always sparing his mounted troops when he can do so without detriment to his plans, a commander may rely upon their full energies being put into the highly important duties which they alone can undertake.

Advanced Guards -

The duty of an advanced guard is to protect the main body from the moment the march of the latter begins. The commander of the advanced guard must know certain details, and must not enter upon the task without obtaining them. He must know all that is known of the situation as regards the enemy, the strength of the force which he himself is to command, and what his own commander proposes to do.

The progress of his command is regulated by the pace maintained by the main body, and by the fact that he is responsible for keeping a given distance ahead of it. This distance will, of course, be decided by the nature of the country and the tactical situation, and by the fact that the duty of the advanced guard is to protect the main body from surprise. In broken, hilly country the need for communication and the possibility of intervention by the enemy, and his capture of good positions, will necessitate far less distance between the advanced guard and its main body than will be required if the country is open, the view extensive, and commanding positions few.

The action of an advanced guard when the enemy is encountered will depend to a large extent upon the intentions of the commander of the force which it is protecting, and whether attack is to be regarded as a part of his scheme when contact with the enemy is established. If immediate offensive action has been decided upon, the first duty of the commander of the advanced guard will be, as it were, to prepare a field of battle for his main body, which is approaching, by seizing positions which will aid the attack. If the offensive is not to be the immediate object when the enemy is encountered, as good a reconnaissance as can be effected should be undertaken to enable the commander of the force to decide upon his line of action.

We have discussed the action of mounted riflemen in the advance, under attack, and there is only one other point to which I need allude here. It is, I gather, much debated, and involves somewhat important principles.

In the Field Service Regulations the practice of dividing a force into several columns and marching on a broad or narrow front is mentioned. Though such a division of force will not involve in South Africa the breaking up of such large masses as are contemplated in Field Service Regulations, it may well occur, as it almost invariably does, that a division into smaller columns for purposes of the march will be made in the case of our own South African forces in war.

As the regulations say, when at a distance from the enemy, the columns march on a broad front, and each should provide for its own protection, but, as the enemy is approached, unity of action is essential, and one advanced guard, common to all the columns, is preferable. It is enough here to say that a common advanced guard is only possible when the same commander is in actual command of the whole force in its divided condition, and that, as soon as any column is allotted an independent task, or leaves the control of the commander of the whole force, it must provide for its own protection. The intervals between the columns will have much influence in deciding this question, but these intervals cannot be laid down, as the tactical situation and considerations of terrain - both very variable factors - must settle the point.

Flank guards may be necessary, and will be found by the mounted troops, but there are no special points as to the tactics which they should adopt which seem to call for discussion.

Rear Guards -

Of the duties of protection which fall to the lot of mounted troops, those connected with rear guards present the most special features. I do not propose to touch upon the action of rear guards of forces advancing against an enemy, for their work is mainly concerned with collecting stragglers, helping on transport, and generally assisting the orderly conduct of the march, apart from tactical considerations, but to discuss the action of such bodies when covering retreats.

This task is trying and exhausting to a degree, and entails great responsibility and strain upon the commander of the force which is charged with it. The main object of the efforts of such a force is to insure the retreat of a body of troops-perhaps a beaten one, in which case its duties are even more exacting-in good order, free from serious damage by the enemy, and under conditions which will enable it to sustain its moral, or regain it if it has been shaken. It must fight, but always with the power of extricating itself and breaking off an engagement. Mounted riflemen, by their mobility, are best able to secure these favorable conditions.

The mobility of a rear guard of mounted riflemen is its chief source of strength in such circumstances. The enemy must be made to deploy and prepare for attack as often as possible. He must be deceived and bluffed as to the strength opposed to him, and this can be effected by the occupation of positions which render it difficult for him to turn the flanks, and ascertain the real state of affairs. His own flanks must be the constant concern of the rear guard commander, and, these secured, a bold attitude must be adopted to impose on the enemy, and the rear guard must deliver counter-attacks which, though sufficiently vigorous to check the enemy and impose upon him, must not be pushed too far.

Communication with the retiring main body must be maintained, and the line of withdrawal and the new position must be carefully reconnoitred before leaving that from which the enemy is being engaged. The line of retreat decided upon, a retirement must be effected before any superiority of the enemy becomes effective, but it must be delayed until the last moment in which it is possible to occupy his energy without detriment to the force opposing him. The mode of withdrawal we have considered in an earlier chapter.

Boldness, resource, and a control of the immediate tactical situation, in circumstances which often render the last condition a matter of extreme difficulty, are necessary to an effective employment of a rear guard. It may be necessary to accept as inevitable the annihilation, or, in any case, the severe handling of a rear guard occasionally, in order to gain time.

In Action -

Protection is necessary while a fight is in progress, but as it is mainly a feature of the general tactics of the attack or defence, as the case may be, it does not seem necessary to make any comments in this connexion here, beyond stating that the free employment of mounted riflemen on the flanks, and in well-controlled reconnaissance, is, generally speaking, the surest way of guarding against surprise, by gaining as clear an idea as possible of the situation before entering the combat, and by forestalling the efforts of the enemy while the fight is in progress by watching his movements.

Halted -

The protection of a force halted, when hostile action is to be expected, calls for different measures. It will be arranged for by a combination of mounted troops and infantry by day, and as far as the actual protection by tactical arrangements by night is concerned, it will be undertaken by dismounted troops-though troops mounted may be used at night if the situation demands it.

It must, however, be remembered that usually the mounted troops will have furnished protection during the day, and that night should be taken advantage of to give horses, at any rate, and, if possible, their riders, rest to fit them to resume their arduous work on the following day. When halted, not a single horse should be used unless the necessity for using it can be plainly justified on the score of absolute need.

The duties of mounted riflemen, for purposes of protection by day, will be practically devoted to reconnaissance, either by reconnoitring patrols, or by observation from small posts of mounted men conveniently placed to watch all likely approaches at some distance from the main body, which, by reason of their power of rapid movement, they can regain quickly. The resistance to be offered by the outposts will be the duty of the dismounted troops again-mounted riflemen on foot or, when the force is mixed, infantry.

Nightfall, however, changes the situation, and the small detached bodies of mounted men can no longer take advantage of their situation for observation purposes, and since, without the power of observation, they are useless and helpless, they must be withdrawn. As I have said, mounted troops should not be employed mounted at night, unless the situation imperatively demands the step. Night provides the careful commander with the chance of recuperation for exhausted men and horses who have been hard at work all day.

The outposts are furnished by dismounted mounted men or infantry, and the employment of mounted troops at night should be restricted to reconnoitring patrols, standing patrols, and what I may perhaps call moving protective patrols. They should all be used sparingly, and only in view of definite circumstances.

Reconnoitring Patrols -

A reconnoitring patrol by night to move towards the enemy, locate him, and watch and report his movements is by far the most effective method of protection at night by mounted riflemen, and should always be employed if conditions seem favorable to good results. The South African Mounted Riflemen Training, 1912, and the British Imperial Yeomanry and Mounted Rifle Training, 1912, say a reconnoitring patrol should be "generally under a non-commissioned officer." It seems to me that the great importance of the work justifies the selection of an office rand an officer specially chosen-for the command of any enterprise of this nature, if it is possible to obtain him.

This method of seeking out the enemy, marking him down, watching him, and dogging his movements is the most effective protection which can be devised, and should be resorted to by mounted riflemen whenever they are halted. In South Africa the large open expanses of country, and facilities for extended observation, aid the safety and escape of small patrols most materially, and reconnaissances should always be pushed far ahead and at distances from their main body, which, it must be allowed, would be impossible where close and broken country restricts the view and favours ambushes. Add to the favorable features of the country the fact that it is the South African troops' own country, and reconnaissances pushed far and wide should be a weighty factor in the successful employment of those troops in war.

The episode of Groenkop in the last war in South Africa is one of the most instructive which can be studied. On the evening of 24th December, 19011 the following British troops were between Bethlehem and Elands River Bridge:-At Mooimeisjes Rust, 270 infantry, 60 mounted infantry, and 1 gun; at Tradouw, 150 infantry; and at Groenkop, 400 Yeomanry and 2 guns. Each of these forces was within three miles of the other two. The Imperial Light horse were at Elands River Bridge, thirteen miles to the east. The Yeomanry had been at Groenkop since the 21st of the month - four days. Beyond one short ride by a small party and an expedition to Tweefontein Farm, three miles away, where a hostile observation post daily kept the camp at Groenkop under its eyes, no reconnaissance whatever was undertaken by this force of 400 mounted men during its occupation of Groenkop, and the hostile observation post was left free to continue its investigations after its temporary ejectment.

As a direct consequence of this passive attitude, a force of the enemy - some 1,000 - was collected at Tyger Kloof Spruit, eight miles north of Groenkop on the night of the 24th, though the intelligence reports had stated on the same day that only 70 of them were within striking distance. Careful reconnaissance during the two or three preceding days had assured the attacking force of the exact dispositions with which they had to reckon, with the result that Groenkop was stormed at 2 o'clock on Christmas morning, and captured in a short space of time-the last shot being fired one hour and a quarter later-with a loss to the defending force of 58 killed, 84 wounded, and 206 prisoners. The retirement of the attacking force was then conducted practically without molestation, with all captured waggons and stores.

As an instance of thorough reconnaissance resulting in striking success, and omission to reconnoitre freely being punished by severe defeat, Groenkop is well worth study.

Standing Patrols -

A standing patrol is a small party sent beyond the outposts, usually by night, which conceals itself near a possible line of approach to give warning of an enemy's advance. Such a patrol should not be sent out unless it is perfectly clear that its employment is necessary, in view of definite information. It is said to be useful because the horses do not move about, and therefore are not much fatigued. They are, however, under the saddle, and get little more rest than if they were moving, and, except when circumstances indicate beyond a doubt that a standing patrol is necessary, reconnoitring patrols by night mean little more real fatigue to the men and horses, and should give far better results.

Moving Protective Patrols -

And now with reference to what I have called moving protective patrols, as distinguished from reconnoitring patrols.

At Groenkop the attack was delivered on the steepest side of the hill, where the storming party massed in dead ground, out of sight of the sentries.

It would have been impossible to do this without alarming the defenders if the base of the hill had been constantly patrolled by small mounted parties during the night. It is such parties that I refer to as moving protective patrols. If there is dead ground which cannot be kept under the observation of the sentries and fire of the piquets, and in which a force may mass under cover of darkness, it should be kept under watch by incessant patrolling by small mounted parties throughout the night.

It is also sometimes necessary to hold positions during the night which are sometimes widely separated-more widely than one could wish, taking into consideration the force at one's disposal. To arrange that fire should cover the intervening space is not enough, unless warning is also given that the enemy is likely to pass through; this, again, may be given by the same moving protective patrols, and instances where such patrols might be of use will no doubt occur to many.

Safety of Patrols -

In concluding this subject of protection, I wish to refer to a method of safeguarding a position when a small force is concerned. Reconnoitring patrols of mounted riflemen will usually be of little strength, for the nature of the work demands that they should be weak in numbers to escape detection. Such small parties are frequently compelled to halt for a night within striking distance of the enemy, and how to protect his little force against surprise and capture is a constant source of anxiety to its commander. He is often compelled to bivouac where the possession of some commanding feature means safety or destruction to his command, according as it is in his own possession or that of the enemy. In such circumstances, sleeping on the position they are to defend is the safest method of protection. If each man sleeps where he will fight if attacked, it will mean that he has only to turn over, grasp his rifle, take advantage of the presence of cover he has prepared overnight, and defend ground which he knows to be essential to his safety, and which he has taken notice of before going to sleep. The necessary sentries should be posted, of course. Unless this precaution is adopted, the position may be rushed, and confusion among men suddenly awakened and flustered will result in capture.

Previous: Part 5, Defence

Next: Part 7, Night Operations

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Militia and AIF, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 6, Protection