Topic: AIF - Lighthorse

The Australian Light Horse,

Militia and AIF

Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 5, Defence

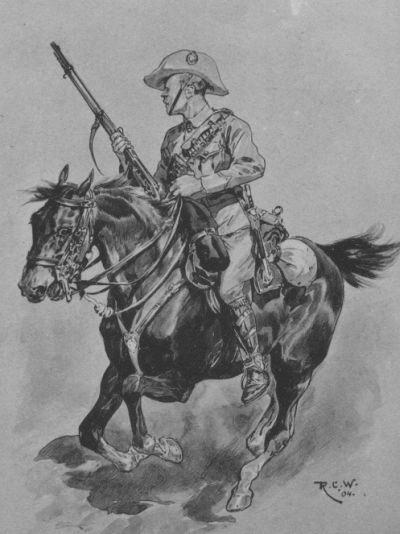

Cape Mounted Rifleman

[Drawing from 1904 by Richard Caton Woodville, 1856 - 1927.]

The following series is from an article called Mounted Rifle Tactics written in 1914 by a former regimental commander of the Cape Mounted Riflemen, Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Collyer. His practical experience of active service within a mounted rifles formation gives strength to the theoretical work on this subject. It was the operation of the Cape Mounted Riflemen within South Africa that formed the inspiration for the theoretical foundations of the Australian Light Horse, and was especially influential in Victoria where it formed the cornerstone of mounted doctrine.

Collyer, JJ, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Military Journal, April, 1915, pp. 265 - 305:

Mounted Rifle Tactics.

III - DEFENCE.

Definition - Uses of mobility - Frontages occupied - Dead ground - Position of reserve - With other arms - Counter-attack - Advanced positions - Lateral communications -The moment to strike.

Turning again to the Field Service Regulations, we find "Defence" described as " the action of that force which postpones the assumption of the offensive and awaits attack in the first instance."

The evils of passive defence have been referred to in the first chapter, and it is not necessary to labour the point further. A defence which contemplates nothing but saving one's own troops, and does not aim at dealing the enemy a severe blow, sooner or later, is regarded as "delaying action," and, as I shall discuss rear guards under. "Protection," I propose to confine our investigations to the defence as defined above-that is, a defensive attitude in the first instance, with the intention to deal a decisive blow as soon as circumstances become favorable to its accomplishment.

How can the mobility of mounted riflemen be turned to the best account in circumstances such as those which I have just stated? Mounted riflemen lend themselves peculiarly to effective work on the defence, and perhaps it is just this fact which gives rise to the criticism which we have considered earlier, that their tactics tend to destroy the offensive spirit which leads to the charge of cavalry and infantry.

A defensive attitude implies inferiority in some respects, possibly temporary, but recognised as enough to call for caution, and an effort to counterbalance an advantage which rests with the attack. The mobility of the arm enables mounted riflemen to hold a defensive position in small strength, and covering an extent of ground impossible for infantry in similar circumstances. This admits of misleading the enemy as to the real strength of the force awaiting attack, and still of keeping a large proportion of the force in reserve, to deal with the situation as it develops.

A position of wide frontage should not, however, be selected, unless the strength available will allow of its occupation, and at the same time of the retention of a force for the decisive counter-attack. The fact that many lines of retreat were usually available and the frontages of the defensive positions were wide, accounts largely for the absence of decisive counterattacks by the. Republican forces in the first stages of the war in 1899-1902. That the frontages were selected by these forces without any intention of regarding this counter-attack as a feature of their defensive tactics is very likely, for several of the early battles, notably Stormberg and Colenso, are instances of opportunities lost when a large measure of success had been gained, and opportunities for counter-attack were afforded to the forces on the defensive.

The position having been selected, with the dual object of making the enemy attack, and dealing him a decisive blow during his attack by a heavy counter-attack, should be held at first with the smallest possible strength deployed. Every advantage should be taken of cover, and natural cover should be improved in order to have more men available for the mobile reserves. The initial force distributed in the firing line, with its supports, on the position must be strong enough to prevent the sudden seizure of any important commanding features included in the line of resistance, and their security must be provided for. Full advantage must be taken of ground to cover by fire all possible approaches, and all dead ground must be carefully watched and denied to the attacking force.

Reference to the records of the last South African War will reveal disaster after disaster directly attributable to the omission to recognise dead ground, and to provide facilities for covering it with fire. In spite of bloody lessons which are at hand to be studied, and studied on the ground if the trouble be taken, hardly a peace exercise is carried out in which dead ground is not ignored both by the attack and the defence.

Once the attacking enemy is aware of the numbers opposed to him, his task is enormously simplified, and the chance of misleading him as to the strength and distribution of his objective vanishes. Unless, however, the attacker is in possession of accurate information, mounted riflemen, well handled, on the defence can mislead, delay, and hamper a far stronger force with much effect, and with a strong likelihood of delivering a counterattack. Efforts at reconnaissance on the part of the enemy are therefore to be anticipated and checked; all avenues of approach must be watched, and arrangements for their protection must be made. The mobility of mounted riflemen confers on them special aptitude for this work.

Having arranged that the position is held in adequate strength, but with not a man or horse more than is required detailed for the task, the large bulk of the force should be kept in reserve, if possible, under the hand of the commander. Where a comparatively large force is employed, so that the rapid reinforcement of any portion of the position is possible as developments indicate the course of the fight, local reserves will be required, and the force which is held back may have to be divided. It must, however, be remembered that every man in the firing line means a man away from the force available for the decisive counter-attack, and that the security of all important features of the position, which would afford advantage to the attack in. advance, should therefore be achieved by the initial dispositions.

As soon as the trend and intention of the attack have become plain, the general reserve should be prepared and placed for the delivery of the decisive counter-attack, and should remain under the direct order of the commander of the force. Constant communication between that commander and the general reserve must be maintained.

Any force kept in reserve for dealing with situations as they must reconnoitre all routes loading to places on the position accessible from their position of readiness, and free communication by visual signalling and other means should be established and maintained between all units positions, and sections of the defending force. The commanders of all such mobile reserves must anticipate their employment by making every preparation while waiting, so that an order to move to any spot is carried out at once, and not delayed to make inquiries, which usually can be undertaken beforehand.

When acting with other arms, mounted riflemen should be employed in the defence in holding advanced or detached positions, securing and reconnoitring the flanks, and especially in reserve for rapid movement to restore the fight when portions of the defence are hard pressed, and in the general reserve. The infantry will hold especially those portions of the position from which movement is not contemplated, and of which a prolonged defence may be necessary, the mobile mounted riflemen being so employed that their power of rapid movement is used to the very best advantage.

Mounted riflemen, since they will, as a rule, occupy positions lightly at first, will have special need for the use of local reserves where a sudden attack may penetrate their line or gain an advantage. By employing their mobility to reach the threatened point, and dismounting under cover as close to it as possible, it is not improbable that the use of the bayonet will be found of much effect. The employment of local reserves is necessary to restore local disorganization of the defence, or to confirm a local success. It is essential that the local reserve, having performed its definite and limited task, should return to its former position of readiness, and a continued advance out of the position after having achieved the task is undesirable, and calculated to end in the tables being once more turned. Given that the situation can be rectified by the use of the bayonet, the fact that the mounted man is employing that weapon, and that his horse cannot follow, may prove a salutary check on the impulse to carry the venture too far. The local reserves will also be used to compel the attacker to use strong forces for the attack and draw in his reserves, so that the counterstroke may find a large force already occupied in the attack when the blow is given. Here, again, by feints and constant use of mobility, mounted riflemen in local reserves may impose upon their attackers with substantial influence on their dispositions.

The decisive counter-attack, for which mounted riflemen are particularly suited, more often than not occurs as the consequence of a mistake on the part of the attacker, and in any case must be undertaken while the situation which is favorable for it exists. The enemy will expect it at some stage or other, and will quickly endeavour to adjust any circumstances which seem to invite it. As Napoleon has said, "'The transition from the defensive to the offensive is one of the most delicate operations in war." A mounted force of good riflemen may be invaluable in such a situation. A correct appreciation of the moment for the effort, instant communication with the force which is to receive the order to make it, and rapid move inept to the scene of the proposed attack, are all necessary. The movement will be decided by the commander of the whole force, but the commander of the general reserve must assure himself that communication is always possible with head-quarters, and the commander of mounted riflemen in such a body must reconnoitre in advance all routes from the position of the reserve to probable scenes of its employment.

Any action which will tend to exhaust the enemy by making him deploy and attack before he reaches the position selected for defence is to the advantage of the defending force, and the employment of mounted riflemen in advance of the position to achieve this purpose is, as I have said, sound and in accordance with principle. The action of mounted riflemen in such circumstances will be much the same as that adopted on rear guards-that is to say, positions will be held so that the enemy is compelled to halt and make dispositions for attack, and perhaps deliver it. The force which has effected the delay caused to the enemy will then retire, while it can do so in good order, to another position, and, if possible, repeat the same tactics.

The necessity for time being spent on detaining the enemy is not as pressing as in the case of rear guard actions, and the main object is to exhaust, disorganize, and damage the advancing force as much as possible, in order that when they arrive at the prepared position their moral and physical energy may have been affected to an appreciable extent. Care must therefore be exercised that the retiring mounted troops effect their successive withdrawals in good order and with deliberation, and that the final retirement to the main position especially presents no feature of hurry or confusion which may have a disturbing influence on the waiting force behind it. Troops driven in from advanced positions in disorder are apt to include those on the main position in their rout when a resolute enemy follows on their heels. The front of the defending force must not be masked by the final retirement, but, on the other hand, the withdrawal should not by its direction clearly indicate the flanks of the main position to the enemy. Suitable lines of retirement which will fulfil the above conditions must therefore be reconnoitred and decided beforehand.

The led horses in defence will be disposed of in the same way as in the attack. Attempts by the enemy to stampede them must be expected and guarded against, and whenever retirement takes place, as it must do in any case with the advanced troops of which I have first spoken, cover from fire while remounting must be secured. Withdrawals from a position will be effected by leaving a few men on it till the last moment, who will endeavour by fire and skilful movement to conceal the disappearance of the bulk of the force from the firing line, and will extricate themselves, as soon as the remainder are in a position to be clear of effective fire when the enemy occupies the vacated position, by rapid retirement, aided by covering fire from the troops who have proceeded them in the withdrawal.

Lateral communication along the positions selected for defence is, of course, essential, and should be as free as arrangements can make it. Again, at the risk of being wearisome, let me lay stress on the need for the fullest reconnaissance of all means of moving along the position from the rear of it, and for constant reconnaissance during the fight. This reconnaissance will be the duty of the mounted troops, and their recognition of its necessity will be a great help towards its accomplishment.

Finally, the mobility of the mounted riflemen in defence should be used to deal the attack sudden, unexpected blows, and the desire to give such blows should be fostered in the arm. Victory, according to Napoleon, is to him who has the last reserves, and, it may be added, uses them at the right moment, for the same famous authority says the art of war consists ni a frapper fort, ni a frapper souvent, mans a frapper juste. In defence, striking at the right moment is of supreme importance; the mobility of mounted riflemen, with free communication and a well-chosen line of movement - each of which may often be secured by foresight-makes them a potent factor in the hands of the commander who is able to select the exact moment for the delivery of his blow.

Previous: Part 4, The Attack

Next: Part 6, Protection

Further Reading:

Australian Light Horse Militia

Battles where Australians fought, 1899-1920

Citation: The Australian Light Horse, Militia and AIF, Mounted Rifle Tactics, Part 5, Defence