Glasfurd was considered to be a meticulous officer with a keen sense of humour. During the Great War he volunteered his services where he quickly rose to Brigadier General. Glasfurd was given command of the 12th Australian Infantry Brigade. On 12 November 1916 Glasfurd was wounded by shell-fire in Cheese Road while reconnoitring the trenches. After a ten-hour stretcher journey from the front line he died at the 38th Casualty Clearing Station at Heilly.

Squadron and Company Training.

Training and Manoeuvre Regulations, section 4 (2) lays down that the training year should be divided into two periods, which will be devoted to

(i.) Individual training.

(ii.) Collective training.

Further on, in the same book, in section 4 (10, (12) and (13), suggestions are made in regard to the application of a similar method to the Territorial Force of Great Britain, the system of training of which somewhat resembles that of the Citizen Forces of the Commonwealth as regards the periods of "Home Training," and "Annual Continuous Training in Camp."

May I here suggest that this book, Training and Manoeuvre Regulations, deserves more attention than it usually gets, and that a study of Chapter 1 will do a lot to help you constantly to keep in view the ideal that all training should be "sound preparation for war."

If citizen troops are to derive full benefit from their annual continuous training in camp, we may take it that during the home training period they should complete their "individual training," and that troops of Light Horse and sections of Infantry should also be advanced so far in "collective training" that they can profitably take their places in their squadrons or companies in order that most of the time at camp may be devoted to squadron and company gaming in field operations.

In these remarks I propose to deal only with squadron and company training during the collective period, but before doing so I would like to point out how important it is that junior officers and non-commissioned officers should be trained during the "individual training period,'' so that they may be of some assistance in training the company when the "collective training period” comes on. I know it is very hard to arrange this, but a good deal could be done by introducing some "method" into the annual training programme of regiments, and it is certain that until a considerable improvement is made cm the present home training arrangements our Citizen Army will not be tuned up to the highest, pitch of which it is capable as regards lighting efficiency. General Haking gives some invaluable hints in "Company Training." This lecture is largely based upon his teaching.

It requires some skill on the part of the regimental officers to decide what to teach during the "individual" period, and what to teach during the "collective" period of training. It is difficult to draw any hard and fast line, but elementary work, which can be demonstrated to the men on the ground near their home training centres, should be selected for "individual" training - whereas subjects which require constant repetition on different types of ground should be allotted "collective" training period.

How is fighting efficiency arrived at nowadays?

In the Regular Army the old idea of turning a man into a machine by means of (1) steady drill, and (2) strict discipline has exploded, and the present system of training each individual's intelligence has taken its place. It is obvious that in a citizen army, it would be useless to attempt to turn men into machines.

(1) In a citizen army Drill must be regarded merely as a means to an end. We must not attempt to copy the precision of regular soldiers. Better results can be obtained at drill by short "bursts" of concentrated effort when all are made to work alertly and strictly “at attention," rather than by long periods of close order work at which, after a certain time, slackness is unavoidable. These "bursts" of concentrated effort "at attention" should always be made when falling in the company; in telling it off; in marching out of camp for a short distance; in marching into camp; and when dismissing. No matter how tired the men may be, officers should insist upon smartness on parade on these occasions at least, and on others too, if only for a short time.

(2) Good discipline really means that courage, respect, cheerfulness, comradeship, emulation, sense of duty, and, in fact, all good "moral" qualities which are favourable to success in war, have been improved by sound peace training; while fear, insubordination, and other undesirable characteristics nave been eliminated. I do not mean that training will make a coward into a brave man, but I do mean that the stock of courage possessed by the average man can be greatly improved by confidence in his leaders, in himself, and in his rifle and bayonet.

I am afraid I am taking a long time to approach the subject of helping you to initiate a sound system of company training, but war is made with men, and in order to get the best work out of different kinds of men, we must consider which of the different methods will produce the best results. Perhaps the best way to ensure good fighting qualities in the Australian Army is to teach it to "play the game" by building it up on a foundation of mutual confidence and respect. Confidence and respect are required on the part of the troops in the superior knowledge, skill, and ability of their leaders; and on the part of the leaders in the devotion of their troops and in their fitness to make the best use of their weapons.

In Training and Manoeuvre Regulations, section 36, under the head of "Collective Training," you will find "The training of the squadron, battery, and company forms the foundation of the efficiency of the Army."

Now, how are we to set about improving the progressive collective training of squadrons and companies at annual camps?

The first thing is to decide upon the best workable system, and the next thing is to explain that system to the brigade majors and citizen regimental officers, so that they can in turn teach their companies. Of course, you may be able to improve upon the system I suggest, but up to the present I have not found traces of any system at all in any of the camps I have attended. It is obviously quite impossible for anyone except regimental officers to train their companies, but it is our job to help them, and a great many need this help in regard to what to teach and how to teach their men.

The guiding principle is contained in the first sentence of Training and Manoeuvre Regulations:-

"Training is the preparation of the officer and the man for the duties which each will carry out in war."

It should be impressed on all ranks throughout, that the sole object of all training is to fit them for their duties in war. If our training is sound preparation for war, it is useful training. If it is not sound preparation for war, then the sooner we stop it and divert our energies into more useful channels, the better for our training.

It is a good thing, of course, to understand as much as we can of tactics - both of our own and other arms, and even of our own or other armies, and of our own and other days. Tactics is one of the subjects about which the more we know, the better; but also, it is a subject about which it is far better to know even a little about our own job thoroughly than a lot in a vague and hazy way about the generals' jobs.

So, I repeat that our job is to prepare for war, and that we have to start by learning our own job and by teaching our men to make the best use of their weapons in attack, defence, and service of security (which means sentry and patrolling duty and reconnaissance). Of course men should be able to understand a tactical operation, but this is best taught by a study of how to use their weapons in war.

Take Field Artillery Training, Yeomanry and Mounted Rifle Training, Engineer Training, or Infantry Training, and read the passage on the "Object and Method of Training." The passages are much the same in each of these books. Importance is laid upon:

Development of a soldierly spirit.

Training of the body.

Training in the use of weapons-drill, etc.

Training in technical subjects.

Suppose now that we were to go out to-morrow to train a company in attack or defence, or the service of security.

How are we to start our training?

First of all we must be quite sure of what we intend to teach, and we must think out beforehand what we intend to do. This means that we must start with some knowledge.

The next thing is to begin with a short, clear, and interesting lecture, say on the previous evening, or on the morning before going out, then follow this with demonstration on ground. So there are two forms of instruction

(i.) Lecture indoors.

(ii.) Demonstration.

First, with regard to lecturing. It is not easy, and most of us dislike it intensely; but it is necessary, so we must all make an attempt. First, we must know the subject - we must be clear as to what we intend to teach. If we start with these two essentials, it goes a long way towards gaining a certain amount of confidence which is required to put our knowledge into words. Study the Training Manuals carefully, study the ground before you work on it, and try to apply the book to the ground. Knowledge of principles can be obtained by a study of the Training Manuals, but, as these books are necessarily very condensed, the difficulty is to expand them into lectures. General Haking suggests that a good form of lecture or explanation is by means of question and answer based on Training Manuals. This is quite easy if you study the book and think. You are referred to "Company Training," by General Haking, in the Army Review, January, 1912, which was re-published in the Commonwealth Military Journal for March, 1912. This will explain the system, and show that a series of questions can be prepared without serious difficulty by any company commander. The points you have to think of are:

What is our object?

How are we going to set about it?

What is the first thing to do?

How will the ground affect this?

What is the next thing to do?

Why not do something else?

And then difficulties-suppose so and so-what then?

Do not be afraid of a question if you cannot answer it. Ask somebody who knows, but be sure to find the answer, so that you can satisfy your men if the same question should occur to them.

Now, as regards out-door instruction. Having cleared up the situation by means of a short lecture the previous evening, and by a few words. of reminder on the ground, and keeping the object clearly in view, you march your troops to the ground you have chosen.

It is a good thing - in fact it is essential to good instruction - to think out your work on the ground beforehand.

A great deal can be done if you get the men to teach themselves.

Suppose you are doing outposts. You can point out the position of the camp you are out to protect, and the direction of the enemy, and the position of the piquet, etc. Then take three men and let them choose their own sentry Posts, or fix the routes they would patrol. The rest of the company can look on and 'criticize-they will usually be good at criticism-it is pretty easy to criticize as a rule. But it rouses interest and makes them think. Then other men could, in turn, take up sentry posts; the advantages and disadvantages of each being discussed.

Time would not be wasted if the critics are in the meantime questioned as regards the “duties" of sentries, etc., as laid down in Field Service Regulations, or employed at visual training or judging distances in connexion with the scheme.

In the defence, the troops in turn might choose their own ground, always with a definite object in view.

Or, again, take instruction in attack. Suppose the company has been lectured on the subject and you are now on the ground. Place them in a fire position 900 yards from the enemy, and tell them they have to get forward t eater the enemy and establish fire superiority preparatory to assault. Remind them of the chief points:-

Rapid advance.

Halt for breath under cover.

While regaining breath re-charge magazine, adjust sights. As soon as they have got their breath rush forward to the best fire position.

Let each section do this over the same bit of ground, the others to point out faults. When each section has finished take the whole company over the ground slowly. Halt at the different fire positions and discuss the same.

Ask men definite questions as regards mistakes.

The subject of drawing up programmes of work is dealt with in a separate lecture, but it is desirable to point out here that while it is very necessary to provide instructive, interesting, and varied work, this can often be done by repetition on different ground rather than by changing the subject of instruction. One sometimes sees “attack and defence," or even “attack, defence and outposts" dealt with in one morning's work. This is not sound, for time is lost, and the men get confused in changing from one subject to another.

A whole morning, or even a whole day, can profitably be spent at “company in the attack," when different phases of the attack are demonstrated and the men shown how the same principles are applied on various types of ground.

SUMMARY.

- Be quite clear regarding what you are going to teach.

- Prepare your work so that you have knowledge and confidence.

- Train for war.

- Do not be satisfied with anything less than the best.

- Instruction to be simple.

- Do not train men in tactics; only in the use of their weapons in attack, defence and protection.

There are two forms of instruction

(i.) Lecture (prepared by means of questions based on Training Manuals).

(ii.) Demonstration on the ground (to follow lecture).

Get men to instruct themselves by demonstration and helpful constructive criticism.

Provide variety by repetition on different ground, rather than by changing the subject and using the same ground, which is probably unsuitable.

In conclusion, let me again recommend you to study “Company Training," by General Haking.

NOTES.

1. The above lecture was followed by three clays' practical work on ground near Sandringham in order to demonstrate a method of company training in attack, defence, and protection. 'The following notes were made during the course of the exercises, and it is hoped that they may prove of assistance to officers in training their units by means of the system referred to in the foregoing lecture. It is difficult for officers to train their men and, at the same time, to solve tactical problems on ground they have never seen before. It is essential, therefore, that they prepare their lectures and demonstrations on the lines given below, and then rehearse the exercises with their subordinate leaders before working them out with their men. For example, one Saturday afternoon might be spent in preparatory work, the following Saturday in rehearsing with the officers and non-commissioned officers; the actual work with the company being carried out on the third Saturday.

2. The first step is to choose the subject of instruction. As “Protection" is one of the special exercises for the year, we will choose “outposts."

3. The next step is to prepare a lecture, taking care that it must be short (ten minutes is enough), clear, and suited to the knowledge of those under instruction. General Haking gives some “questions and answers" in his book, “Company Training." These are produced in Appendix I., and another specimen lecture is given in Appendix II. Officers are recommended, however, to prepare their own lectures, because they learn a great deal by doing so.

4. Having explained the subject by means of a lecture one evening, we proceed on the following day to train our men by means of a demonstration on the ground. It is worth while repeating once more that we can only train our men by means of constant practice on the ground of the duties they will have to carry out in war. The outline of a scheme, which was actually worked out on the ground, will now be explained.

COMPANY EXERCISE, “OUTPOSTS," CARRIED OUT NEAR MELBOURNE.

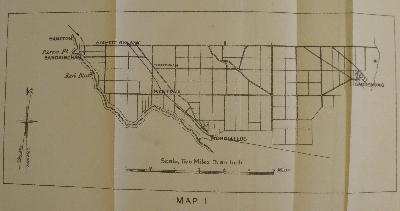

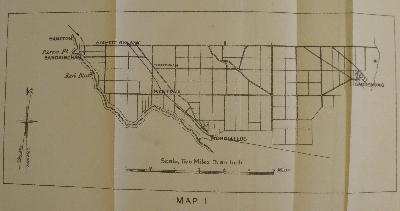

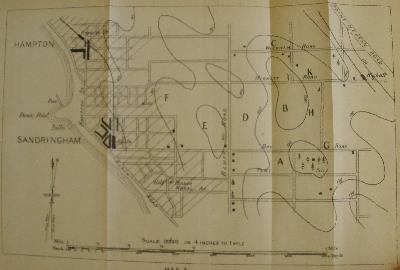

Reference Maps 1 and 2.

Map 1

[Click on map for larger version.]

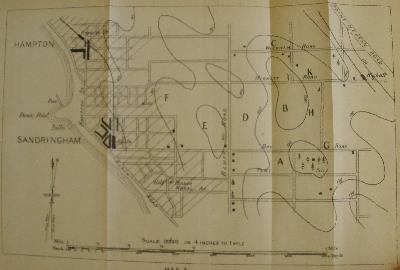

Map 2

[Click on map for larger version.]

Map 2 NOTE:-

The detail given in these paragraphs should be summarized and Issued to the non-commissioned officers and men under instruction on typed or hectographed slips of paper.

NOTE:-

During company training in outposts, we do not want to teach the men to solve tactical problems, but only how to make the best use of their weapons on outpost duty. Still we must have a small scheme.

GENERAL IDEA.

A Western Force, in friendly country, is advancing against an Eastern Force.

NARRATIVE.

A Western Detachment, strength as under, arrives at SANDRINGHAM at 2.00 p.m. 3rd June. A hostile detachment of about equal strength is known to be at DANDENONG.

Western Detachment—

Brigadier-General Jones Commanding.

Headquarters 1st Infantry Brigade. A Squadron 1st Light Horse.

1st Battery, Field Artillery; 1/3rd Artillery Bde. Ammn. Column. 1st Engineers (Field Company).

No. 2 Section, and Engineers (Signal Unit).

1st Infantry Brigade (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th infantry). and Company, 1st Divisional Train,

1st Field Ambulance.

There are no other troops, either friendly or hostile, within 25 miles. Brigadier-General Jones decides to halt for the night on arrival at SANDRINGHAM. The following instructions were issued while on the march.

INSTRUCTIONS FOR O.C. OUTPOSTS.

Colonel Brown, Commanding 1st Infantry.

G. 27. 3rd. I intend to halt at SANDRINGHAM for the night. You will be O.C. outposts. A hostile detachment of about equal strength is at DANDENONG. Our Light Horse patrols are in touch with those of the enemy north of MORDIALLOC. There are no other bodies of troops, either friendly or hostile, within 25 miles. In case of attack, I intend to occupy the high ground which runs N. & S. astride BAY ROAD, about Y4 mile from the sea.

The detachment will bivouac on the open land about 900 yards N.E. of SANDRINGHAM Railway Station.

The outposts will consist of 1 troop 1st Light Horse and 1st Infantry, less 4 Companies. 2 Companies 1st Infantry will act as inlying piquet.

The outposts will be relieved when the advanced guard has passed through them about 7.o a.m. to-morrow.

(Signed) J. JONES, Br. Genl., Commanding Western Detached Force.

HAMPTON, 1.0 p.m.

5. On receipt of these instructions the outpost commander rode on ahead to make a personal reconnaissance; after which he issued his orders in accordance with Field Service Regulations, Part I, Section 78 (2).

6. On arrival at the rendezvous, the company was marched to point E, where its commander gave a brief summary of the chief points in the lecture already given.

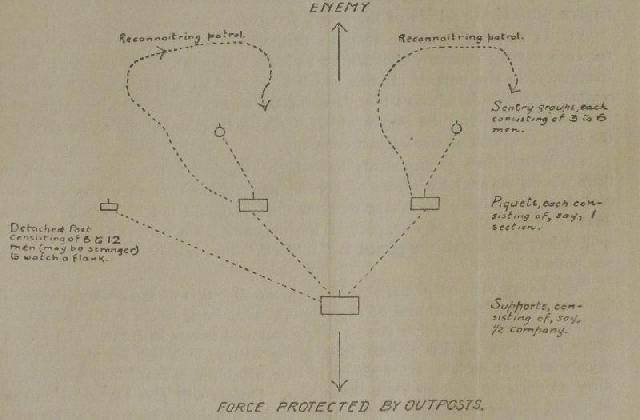

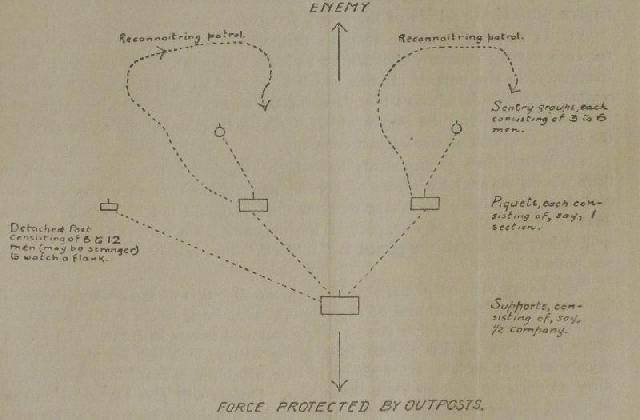

The company was divided into sentry groups, piquets, support, reconnoitring patrols, and a detached post, each of these parties being only a few yards apart so that every man had a chance of seeing the other portions of the outpost company and of hearing the duties explained and the instructions issued. It should be made clear that this diagrammatic subdivision of the company is purely for instructional purposes.

7. The company commander at point E then explained the outpost commander's orders to his men as follows:-

(i.) Our detachment halts to-night, 3rd-4th June, near SANDRINGHAM. (and indicates point F on the ground). In case of attack the detachment will occupy the high ground astride BAY-ROAD north and south of point E, where we are now. A hostile detachment of about equal strength is at DANDENONG (over there. about 11 miles east). Our Light Horse patrols are in touch with those of the enemy about 5 miles east of here. There are no other bodies off troops, either friendly or hostile, within 25 miles.

It will be instructive, at this stage, for officers to write out the orders which would be issued by the officer commanding outposts, as well as by the commanders of any of the outpost companies.

(ii.) The outpost companies will occupy the general line from the sea (over there, near the end of BLUFF-ROAD) through the points A, B, and C (indicated on the ground), to a point over there, about J mile N. F. of HAMPTON STATION. Outpost mounted troops are out in front over there, furnishing standing patrols at road junctions along the POINT NEPEAN-ROAD.

(iii.) Our company is No. 3 outpost company, and is allotted the frontage A, B, I, from BAY-ROAD inclusive to HIGHETT-ROAD inclusive. The company is responsible that none of the enemy penetrate this section of the outpost line.

(iv.) In case of attack, the piquet line will be the outpost companies' line of resistance. The piquets will not retire without orders.

(v.) No traffic through the outpost line is allowed by night. No smoking is allowed after 6.o p.m., by which hour all fires are to be extinguished.

(vi.) The outposts will be relieved when the advanced guard passes through about 7.o a.m. to-morrow.

(vii.) I will be with the support.

8. The outpost company commander further explained to the men that their duty was, firstly, to watch for the enemy's approach and so provide against surprise, and secondly, to resist the enemy (should he advance) on the line A, B, I.

The degree of the resistance to be offered by the outposts must at all costs check the enemy on the line A, B, I, until the main body has had time to move from F and occupy the high ground north and south of E.

Our detachment will take about twenty minutes to assemble (see question 10, Appendix I.), and another twenty minutes to occupy the ridge; say, total, forty minutes.

Therefore, to be on the safe side, the outposts must check the enemy for three-quarters to one hour; and it may be necessary for us to sacrifice ourselves to gain this time to enable our commander to put his plan of action into effect. Our company must act in conjunction with the companies on both flanks.

9. When preparing the work, No. 3 outpost company commander decided to post three piquets (each of one section) and one support, as follows:

No. 1 Section: Piquet astride BAY-ROAD, near A.

No. 2 Section: Piquet near B.

No. 3 Section: Piquet astride HIGHETT-ROAD, near 1.

No. 4 Section: Support to be posted near D.

No. 4 Section is now told off as “covering party " preparatory to removing the remainder of the company to the ground allotted. No. 4 Section sent out three patrols (each of four men), the remainder of the section following as a support; it is not sound to scatter the whole covering party across the front in “daisy-chain" formation. The covering party, like even other body of troops. must be given clear instructions, which might run as follows:-

A 7. 3rd. Instructions for and Lieutenant Keene, i /c. covering party.

(i.) There is a hostile detachment near DANDENONG, about 11 miles east of here. Our Light Horse patrols are in touch with those of the enemy about 5 miles east of here. Our detachment halts at F (indicated), with outposts on the line A, B, C.

(ii.) Our company is No. 3 outpost company, and is responsible for the frontage A, B, I.

(iii.) Your mission is to prevent the enemy overlooking, or interfering with, the outposts until the piquets and sentry groups are posted.

(iv.) In case of attack you must delay the enemy as long as you can, and fight your way back to the piquet line.

(v.) Unless seriously attacked, you must hold your ground until recalled by me.

(vi.) You should go out at least as far as the road leading from G to K, but use your own judgment in carrying out your mission. (vii.) Reports to B.

(Signed) Z X, Captain, Commanding No. 3 Outpost Company.

Point E., 2.30 p.m

10. On active service, after the "covering party" had gone out, Nos. 1, 2, and 3 Sections would be sent, under their commanders, to their approximate piquet positions near A, B, and I. respectively. But for purposes of demonstration, the instructor carried out the work of posting each piquet in turn for the benefit of the whole company; part of the company being told to select their position as a piquet, the remainder being told to observe and being subsequently asked for their criticisms. The instructor then pointed out the advantages and disadvantages of the different positions selected, and decided which was the best, giving his reasons.

A piquet-post should be well concealed; it should have a good field of fire at close ranges; its flanks should be strong; it should not be easily surrounded; and it should support and be supported by the piquets on either flank.

The outpost company commander will confer with the commanders of the companies on his flanks, in order to arrange for this mutual support. The outpost company commander is responsible for placing the piquets, but the subalterns and non-commissioned officers should be trained in this duty.

11. A piquet has to find one or more sentry groups (to be relieved after eight to twelve hours' duty) ; sentry over piquet three reliefs; reconnoitring patrol-three reliefs (uncertain times) ; men to dig fire trenches and latrine trenches, as well as messengers and men for wood and water fatigue, cooking, &c. The piquet commander has to see that his men have ammunition, food, and water before they go on duty. The fighting efficiency of a piquet and the comfort of the men are both dependent upon the piquet being well organized. The following system of "telling off" a piquet has been found to work well. Suppose the piquet is a section at about war strength, say, twelve files, the following commands are given:

“Section, number. Files 1 to 3, under Corporal Smith, you are sentry group over there near G. Corporal, post the group. I will visit you in ten minutes' time.

The remainder of the section form the piquet.

Files 4 to 6 are first relief, under Sergeant Y. Files 7 to 9 are second relief, under Private O.

Files 10 to 12 are third relief, under Lance-Corporal P.

Second relief, stand fast. Remainder, four paces outwards close march.

Reliefs, number (each relief numbers 1, 2, 3).

Nos. 1 and 2 files of each relief-slope arms. You are reconnoitring patrols.

No. 3 front rank of each relief-slope arms. You are piquet sentries. No. 3 rear rank of each relief-slope arms. You are messengers or spare men.

The first relief will be on duty from now onwards for four hours (or two hours if troops are fatigued or by night).

The piquet is to remain ready for action, with accoutrements and rifles laid ready for use.

Order arms. Stand easy."

The advantage of this method is that each “relief” is a complete party, under its own commander, and the company commander knows at once where to look for the relief on duty.

The piquet commander then posts the piquet sentry; explains the orders and the duties of each man (see Appendix II., paragraphs 15 to 18), sends out the first relief reconnoitring patrol; makes cover (and sometimes "dummy" trenches); explains what to do in case of attack; practices falling in rapidly, so that all may know what to do and there may be no confusion; and tells off the various fatigue parties.

The above system is capable of modification. For example, if the piquet is weak, we will not be able to detail more than perhaps one sentry group of three men; or we might post a pair of sentries; or, in suitable country, the piquet sentry might do the work of a sentry group. Again, it may be advisable to find patrols from the supports. Remember there is no "formalism" about outposts; the arrangements made must be the best under the circumstances.

At this stage especially the company commander must depend upon his subordinate leaders to assist him in teaching the men.

12. For purposes of demonstration, some men were sent out from piquets A, B, and I to post themselves as sentry groups near G, H, and K, as described in paragraph 10. The instructor pointed out to the onlookers what was right and what was wrong; then a party of the onlookers repeated the exercise; and, finally, the instructor decided where the sentry posts ought to be, and why.

It was found that the question of mutual support and the enemy's lines of advance were not always sufficiently considered, and that the sentries' line of retreat often masked the fire of the piquet.

Piquets can sometimes be placed so as to extricate sentries by fire. The country near BAY-ROAD and HIGHTETT ROAD is close, and the view is restricted; so it would need to be thoroughly searched by patrols.

13. The handling of patrols, which needs thorough instruction and frequent practice, can only be briefly referred to here. A patrol leader must constantly ask himself: “What is my mission? Will this action help me to accomplish my mission? How am I to make certain that the news reaches my commander? Which is the best place to go to? What is the best way of getting there? What is the best formation under the circumstances? Where will the enemy expect to see a patrol? and so on.

While some of the men are being instructed as sentries or reconnoitring patrols, the remainder can observe and criticize, or they can be exercised in visual training and judging distance, or taught their duties with the piquet.

14. So far this article has dealt chiefly with day dispositions. It will, however, provide a whole afternoon's work as it stands, and perhaps enough has been written to explain this method of instruction.

There is a great deal to be learnt by this form of exercise. For one thing, one instructor cannot teach a whole company by himself; he must have trained subalterns and section commanders qualified to pass on correctly what they themselves have been taught.

Again, it is impossible to carry out this sort of systematic instruction unless the work has been carefully prepared and rehearsed on the ground. One cannot train one's men and make up one's scheme of work at the same time, as one goes along. Even when the work has been carefully prepared, it will improve every time it is repeated.

15. It is now proposed to deal briefly with a few points of general interest in connection with outposts. To begin with, it is essential to be quite clear regarding the objects to be attained by all protective troops. These are, firstly, by means of reconnaissance, to obtain timely warning of the enemy's proximity; secondly, by means of resistance, to ensure that the enemy is held off until the commander of the main body 'has time do put his plan of action into effect. This “plan" is not necessarily defensive. Our commander may intend' to attack the enemy, in which case the outposts must secure any tactical points which may assist the development of the attack of the main body. Each case must be dealt with according to circumstances. There are no fixed rules for outposts. Their strength, composition, and disposition vary by day and night according to the nature of the country, the proximity, strength, and characteristics of the enemy, and the plan of the commander. For instance, the distance between the sentry groups and piquets depends upon the facilities for observation, but should not usually exceed about a quarter of a mile. The distance between the other portions of the outposts depends upon the action if attacked; it is a good thing actually to practice reinforcing the piquets from the support, and so on. Again, the frontage allotted to outpost companies depends entirely upon circumstances; a company may find itself responsible for half a mile or more. The frontage allotted to sentries to watch should overlap.

16. It is often thought that the normal procedure is for the outposts to fight until the main body comes up to them, i.e., that the line of resistance of the outposts is usually the fighting position of the main body. Sometimes, especially with small forces, this may be the case. But it should be clearly understood that the line of resistance of the outposts is not necessarily the ground which the main body would hold in case of attack. This is made quite clear by a study of Field Service Regulations, Part I. (reprint 1912). In section 76 (2) it is stated that

“The distance of the outpost position from the main body it regulated by the time which the main body requires to prepare for action, and by the necessity of preventing the enemy's artillery from interfering with the freedom of movement of the main body."

Then, again, to comply with Field Service Regulations, section 78 (2) iv, the commander of the outposts should give detailed orders regarding "Dispositions in case of attack. Generally the line of resistance, and the degree of resistance to be offered;" i.e., by the outposts. It should be noted that the line of resistance by night does not necessarily coincide with the line adopted by day.

Field Service Regulations, section 79 (1) certainly states that "Retirements of advanced troops upon a line of resistance are dangerous, especially at night," but it will be seen the line o f resistance o f the outposts is here referred to.

In short, the outpost line of resistance must be selected with a view to obtaining sufficient time for the commander of the main body to put his plan of action into execution. This time can be obtained either by fighting a delaying action towards the main body, or by obstinate defence until the main body domes up to the outposts.

APPENDIX I.

The following questions and answers on "Outposts" are extracted from “Company Training," by General Haking, a book which will prove of great assistance to regimental officers in training their men:

When two nations declare war against each other what action is taken by the opposing armies?

They usually march towards each other.

Do they meet and fight the first day!

No, they have to march several days before meeting.

What do they do at night?

They halt and the troops go into billets or bivouac, and the men go to sleep.

Is it safe for all the men to go to sleep?

No, because the enemy might surprise them when they were asleep, they would not be ready to fight, and they would be defeated.

Must all the men stay awake?

No, because if they did the army would get no rest, and after two days or so they would be completely worn out by marching without sleep, and would be unable to keep awake or to fight when the enemy was met.

How many men must stay awake?

We shall he able to answer that question more definitely later on, meanwhile it is sufficient to say that the army does not take very long to get ready to fight, and small bodies of men posted in good places between the army and the enemy can delay the enemy's advance long enough to enable the main body, who have been asleep, to get ready for battle.

How long does it take for a force to get ready for battle?

That depends greatly upon the size of the force. Suppose the company came in here last night after a long march in the enemy's country, and slept in these barracks, or bivouacked on the barrack square, with their rifles, ammunition, kit, etc., alongside each man, it would not take the company more than a few minutes to turn out and attack any enemy that came along.

How long would it take the whole battalion to turn out and get ready to fight?

It would take longer because there are several companies to be got into proper formation for fighting. A battalion in battle takes up a wider front than a single company, and consequently the flank men have further to go to get into their proper positions.

The space occupied by a battalion should be compared on the blackboard with that occupied by a company.

How long does it take for a brigade to get ready?

Still longer, because there are four battalions, and when the brigade is deployed for battle it naturally takes up much more room than one battalion, and so it goes on to a division and an army. The larger the force the longer it takes to get ready to fight, either when it is halted during a march or when it is assembled in bivouac.

How long in actual time would it take for a company to turn out?

Suppose we were all asleep, and everybody knew exactly what he had to do and where he had to go if the enemy attacked, it would not take us more than five minutes to put on our accoutrements, charge our magazines, and deploy outside the bivouac. It would take a battalion about ten minutes, a brigade fifteen to twenty minutes, and a division, with all its artillery from three-quarters of an hour to an hour.

Is the force in a good place for fighting directly it has deployed outside the bivouac?

That depends entirely upon the nature of the ground round the bivouac. Some ground might be suitable and other ground might be very bad. For example, a force very often bivouacs in a valley where there is plenty of water to be found for the men and horses, but a valley would not be a good place to commence a fight, because a valley has hills or rising ground on each side of it. If the enemy gets on to that rising ground he will be able to see everybody in the valley and shoot them, whilst the people in the valley will only be able to see the rifles of the enemy being fired over the crest of the ridge, and can see very little of the men who are using those rifles or of the enemy's troops that are in support or reserve.

Draw on the blackboard a section of a valley showing the troops who have deployed close to their bivouac engaging the enemy who have deployed a firing line along the crest of the opposite ridge.

What are we to do to prevent this?

It is absolutely necessary for our main body, or the greater part of it, to occupy the ridge in proper fighting formation before our outposts are driven back over it. It is clear, therefore, that more time is required than at first appeared necessary, because the force has not merely to wake up, put on its accoutrements, saddle or harness the horses and deploy close to the bivouac, it has also to march to the ridge, and the time taken over that operation depends upon the distance of the ridge from the bivouac.

Suppose there is no ridge close by, what is to be done then?

The ground must be either perfectly flat, when the enemy would have no advantage over us, or else there must be some hill or commanding ground within rifle or artillery range of the bivouac.

Suppose there is such a hill, how is it to be dealt with?

If it commands the bivouac, and the enemy could get guns on to it at night and shell the bivouac as soon as it was light enough to see, we must either move the position of our bivouac or occupy the hill with outposts to prevent the enemy getting hold of it.

How far off can the artillery shell the bivouac?

They can do it easily at a distance of two and a half miles.

Are we to send out outposts two and a half miles away from the bivouac?

That depends a good deal upon the size of the force. If it is a small force it does not take up much room in bivouac, and can easily be hidden, and then this distant point could be lift unguarded. With a large force, which takes a long time to get ready for battle, the outposts being nearly three miles away would be an advantage, because if the enemy were to attack in strength it would take him a longer time to drive the outposts back three miles than it would a shorter distance.

Is it a good thing always to but the outposts as far away as possible?

No, because the further the outposts are sent away from the bivouac the greater is the number of men who are required to occupy the outpost position, and who, consequently, are deprived of their night's rest.

Why does it take a larger number of men?

Draw on the blackboard one semi-circle of outposts a mile away from the bivouac and another semi-circle two miles away, and show that if the posts in each case were about the same distance apart, as they would have to he, double the number of posts would be required for the further position, and, in consequence, double the number of men.

What have we learnt so far?

1. That whenever a force halts for any length of time it must be protected by small detachments placed between it and the enemy, so that the main body may have plenty of time to get ready to fight before the enemy is upon them. These detachments are called outposts.

2. That them outposts must not he composed of more men than is absolutely necessary, so that as many men as possible may have a good night's rest.

3. That the outposts must prevent the enemy from occupying the ground near the bivouac which his been selected as most suitable for the main body to hold at the commencement of the fight if the enemy attacks.

4. That the outposts must occupy any ground whence the enemy could fire into the bivouac.

The next question that arises naturally in our mind is how are these outposts arranged?

Before answering this question let us hate a clear idea of what we wanted to do.

1. We want to gain information as early as possible regarding the approach of any hostile force.

2. We want to ascertain whether that force only consists of a few scouts who could do no harm to the main body or whether it is a serious attack.

3. We want to prevent hostile scouts from gaining any information about the strength or position of our main body.

4. We must delay the advance of a large hostile force until our main body has had time to get ready to attack and defeat it.

How are we going to gain information?

If you have made an appointment to meet a young lady at 5 o'clock in the afternoon, you go to the place arranged, and if she is late, as she generally is, you look in the direction you expect her to come from. The enemy is not so pleasant to meet, but you treat him in exactly the same manner. Men, called sentries, are posted all along the front watching every direction from which the enemy could come, so as to give immediate warning of his approach.

How far can a sentry see to his front?

That depends partly upon his eyesight, but chiefly upon the nature of the ground. In almost every kind of country the view is restricted by trees, hills, farm-buildings, villages, hedges, &c. In some places it is difficult, if not impossible, to find a place for a sentry where he cab see for more than 50 or 100 yards. In such a case the enemy can get very close to the sentry without being observed.

How do we get over this difficulty?

We send out small parties of two or three men to scout forward beyond the sentry, and examine any ground the sentry cannot see. These small parties are called patrols.

How often are they sent out?

That depends upon the amount of ground in front which the sentry cannot see. If there is a good deal of such ground the patrols would have to go out at least once every two hours by day, and even more frequently at night. As a rule, however, by day ground which cannot be seen by one sentry can be watched by another sentry on the flank of the first.

How is this managed at night when the sentry can only see a short distance in front of him?

Although a sentry cannot see far at night it is equally difficult for the enemy in large bodies to move across country in the dark, and consequently when the country is intersected by woods, hedges, streams, &c., the enemy are compelled to keep to the roads and tracks. If sentries are placed well forward on these roads, they can give sufficient warning of the enemy's approach. When it is possible for the enemy to move off the roads or tracks it is essential that a frequent system of patrolling should he maintained.

How are we going to prevent the enemy's scouts from getting past our sentries and ascertaining the position and strength of the main body?

The scout in war does not walk through sentry lines in the same bold manner that he adopts in peace operations. Nevertheless there is always a possibility that stray scouts may get through the outposts by night. Even if they do it is not easy for them to get any definite information as to the strength of the main body, and they cannot do the main body any harm; furthermore, they must get back again before daylight, or they are almost certain to he captured. It would deprive too many men of their night's rest to place sentries so close together as to render it impossible for a very daring hostile scout to get through, and it is a risk which must be accepted.

How are the sentries to ascertain whether the enemy consists of a few men, who could not hurt the main body, or a large force?

If there are only a few men they will be likely to do their best to avoid the sentry-they are out to get information, not to drive in the outposts. It will be seen later, however, when we discuss the question of delaying the enemy if he advances in strength, that the resistance which must be offered by the outposts will disclose the strength of the enemy.

How are we going to delay the enemy?

The sentry cannot stop or even delay a large hostile force for more than a minute or two, because they can get round his flanks and cut off his retreat. In order to delay the enemy we require a stronger force, called a piquet' which is posted somewhere in the rear of the sentry, and which can bring a heavy fire to bear on the enemy if he advances and compel him to deploy a much larger force than the piquet. This will take some time, and it will take still longer for this hostile force to gain superiority of fire over the piquet, or to rush it successfully with the bayonet. It will take the enemy still longer to work round the flanks of the piquet, especially at night, and endeavour to cut off its line of retreat.

What sort of place should we choose for posting the piquet?

Some locality where there is a good field of fire in the direction from which the enemy is most likely to advance, and where there is no other place close by, especially on a flank, which commands the ground occupied by the piquet, and which the enemy could occupy and thence fire into the picquet.

Would such a position be suitable by night as well as by day?

The field of fire by night is always very restricted, because the men cannot see, so that the importance of commanding ground is not so great. In fact, a better fire position can frequently be selected on low ground looking up over the crest of a rising slope in front, with the sky as a background. On the darkest nights figures moving over the sky-line can be observed at a considerable distance, whereas, if the position selected is on the top of a hill the only view is into a valley where everything is shrouded in pitch darkness.

If the suitability of a position by day does not agree with that by night, will it be necessary to change the position of the piquet?

Yes; and there is another reason why it is desirable to change the position of the piquet by night. The enemy may have been able to discover its position during daylight, and he may have made plans to attack it during the night. If, when he advances, he finds that the position of the piquets has been changed. It will come as a surprise to him, and his plans will be upset.

When changing the position of the piquet to a locality suitable for outposts by night is it usual to draw it back or establish it further forwards?

It is best to send it further forward for two reasons. First, the enemy will come across it before he expected to meet with any opposition; and, secondly, the sentry is usually much further away from the piquet by day than he is by night. He is generally on high ground by day where he can get a good view, but this is not a good place for observation by night, because he has no sky-line to look over. It would be a mistake to give up this ground to the enemy, and consequently the sentry is pushed still further forward; which means that the piquet must also be moved forward so as to close up to the sentry.

Are the piquets and sentries always moved forward at night?

No, it depends a great deal upon the ground. If the country is very close and it is practically impossible for large forces of the enemy to move off the roads or tracks, or if there is a river in front of the piquet, its flanks are then secured by the impassable nature of the country, and it is only necessary to arrange for a heavy fire towards the only approach the enemy can select, namely, the track through the close country or the bridge across the river.

Is it possible to lay down any exact rules as to the selection, of the position for a piquet or a sentry?

No, because the ground is never the same, and a position which is suitable in one locality is quite unsuitable in another. We shall see, however, when we come to study the details of sentry and piquet work that there are a few general rules or principles which can be applied with some certainty in definite types of country which we are likely to meet, and these principles will be of great use to us when we are deciding what to do.

How long is the piquet to delay the enemy?

As already stated, that depends upon the size of our force and the distance it is from its fighting position outside the bivouac. In any case the piquet must put up a very serious resistance, and be prepared even to sacrifice itself, if it is necessary, for the safety of the whole force. For this reason piquets are very carefully entrenched, obstacles are made in front, and bushes, trees, and hedges which interfere with the field of fire are cut down.

How are the companies arranged on the ground so as to provide these piquets?

It is usual to allot a certain front of ground to one company, with other companies to its flanks until the whole outpost position is carefully guarded. These companies are called outpost companies. Sometimes, owing to the nature of the country in front, one piquet is sufficient for each outpost company, sometimes two are necessary, and sometimes three.

If one Outpost company has to find three piquets, and another outpost company only one piquet, will not the strength of the piquets vary considerably?

Each piquet generally consists of one section. The officer commanding a company finding three piquets would endeavour to make each piquet even smaller than one section, so as to retain in his hand a strong support which could reinforce any particular piquet which is being heavily attacked. The company which is furnishing only one piquet will be placed at some very important locality, which the enemy is very likely to attack.

In such a case would any difference be made at night?

It is better, if possible, at night to avoid any movement of reinforcements, because contusion is likely to result. The reinforcements come up in the dark, they may not know exactly where to go to, and they may arrive too late to prevent the piquet from being driven back.

What is the best plan to adopt at night when there is only one piquet?

It is better to place the whole company in the spot selected for the piquet, so as to avoid any movement when the enemy attacks.

Appendix II.

Specimen Lecture on Outposts, Suitable For Company Training.

1. Every body of troops, whether at rest or on the march, must protect itself against surprise. The troops detailed for this duty of protection to a force at rest are called “outposts."

2. When a force is on the march, it is protected by advanced, flank, and rear guards, and these protective troops are relieved by the outposts after arrival in camp.

3. The O.C. force details an officer to command the outposts, and gives him the necessary troops for the purpose; these troops are called “outpost mounted troops" and "outpost companies." The O. C. outposts allots to each outpost company a definite section of ground for which it is responsible. It is a point of honour with every outpost company that no enemy is allowed to penetrate the section of the outpost line for which it is responsible.

4. We will now consider the action of one of these outpost companies, and imagine that there are similar companies on our right and left. This will give us an idea of how a force at rest is protected in war.

5. Having received his instructions, the outpost company commander marches his company with proper precautions (i.e., he sends out scouts or patrols to make sure the country is clear of the enemy) to the ground he is to occupy.

Before he reaches his position, he halts the company under cover, sends out a “covering party," and himself goes forward to reconnoitre. The covering party usually consists of patrols (three to six men), followed by a support, whose duty it is to prevent the enemy from interfering with, or overlooking, the outpost line while it is being posted. The commander of an outpost company has to remember that he is responsible for protecting the men resting in camp. He must guard against surprise, and if he is attacked he must fight hard in order to gain time for the main body to turn out, so that the commander of the force may put his plan of action into effect.

6. So you see that the outposts have a double duty: firstly, reconnaissance or watching the enemy so that he cannot make a move without being detected secondly, resistance, or checking the advance of the enemy until the main body is ready to fight.

7. Keeping these two duties in mind, the commander of the outpost company first selects his line of resistance, that is to say, the line he intends his company to hold if attacked. As the company must' be prepared to make a protracted resistance, they must have a good field of fire and he concealed from view, for one of the first principles of outpost work is to see and hear without being seen or heard. In choosing this line of resistance, the commander of an outpost company must consult the commanders of the companies on both flanks, so as to arrange for mutual supporting fire, and make certain that no ground is left unwatched or unprotected.

8. The next thing is to select the outpost company's line of observation, and to decide on the number of sentry groups to be employed. If observation is difficult we must use reconnoitring patrols to search the ground we cannot see. Reconnoitring patrols are given a definite task, told when to go out, when to return, and their approximate route. The conduct of reconnoitring patrols is an art in itself, and will be dealt with separately. Standing patrols are sometimes employed to watch certain approaches in front of the outpost line. Their du y is chiefly observation. They are not often used by Infantry, but standing patrols of mounted troops or cyclists are most useful.

9. Having done all this, the outpost company commander goes back and chooses the position for his supports, and then he is ready to bring his troops on to the ground they are to occupy.

10. Now, you see that an outpost company is divided as follows:

Force Protected by Outposts

It must be clearly understood that this diagram is merely an example. The placing of outposts depends entirely on the features of the country and the nature and proximity of the enemy. There must be no “formalism." There is sometimes a reserve to the outposts; when there is no reserve an "inlying piquet" takes its place.

Reconnoitring patrols can be provided from either the piquets or supports; their duty is to search the country in front of the outposts or to watch the enemy.

Detached' posts are sometimes used in case of necessity to watch important places. They act similarly to piquets.

Usually the sentry groups consist of from three to six men under a non-commissioned officer or old soldier. One of these men is always on the watch, while the others lie close to him so that he can arouse them (by a gentle kick, perhaps) at a moment's notice. The advantage of this system is that the sentry has his “mates" close beside him, and should he fancy he hears or sees anything he can at once arouse them to verify his suspicions. Moreover, the sentry can be relieved every two hours without causing the movement of parties, which might be seen by the enemy's scouts.

It is not always necessary to have sentry groups in front of the piquets, for sometimes the piquet sentry can see all that is required from the piquet itself. The main thing is to provide for efficient observation.

Communication must be maintained at all times between all parts of an outpost position.

11. It is clear that these little sentry groups are not strong enough to resist the enemy in case of attack; they are only intended to detect his advance.

12. The duty of resistance usually falls on the piquet, which consists of a party, very often a section," under an officer or a non-commissioned officer. The piquets provide the reliefs of the sentry groups.

13. As no one knows where the attack will come from, it is usually best for each outpost company commander to keep a support which can be sent, on emergency, to any part of his line which is in need of assistance. The outpost company commander chooses the place for the support and gives its commander instructions regarding the degree of readiness to be maintained, as he does for the other fractions of the 'outpost company.

14. When these arrangements have been completed, the piquets march to their places, covered by scouts of course, and taking care they are well concealed, for it is very important that the enemy should not be able to "mark down" the positions of any part of the outposts. On arrival at the selected spot orders are issued, the piquet is "told off” into reliefs, and sentry groups are posted.

15. Every man on piquet should know the direction of the enemy, the positions of the next piquets and of the support, what he is to do in case of attack by day or by night, whether there are any mounted troops in front. The piquet sentry must look out for signals from group sentry, look out for signals from piquets on right or left, warn piquet in case of alarm or suspicious occurrence, allow no noise or straying from the piquet. Orders will also be issued on the subject of ranges, land marks, sanitation, smoking, lighting fires, and cooking.

16. Commanders of sentry groups must know that no one other than troops on duty, prisoners, deserters, and flags of truce will be allowed to pass through the outposts either from within or from without, except with the authority of the commander who details the outposts or of the commander-in-chief. Inhabitants with information will he blindfolded and detained at the nearest piquet pending instructions, and their information sent to the commander of the outposts. It will often be necessary to harden our hearts when dealing with inhabitants. (See also Notes, para. 7 (v).

On the approach of a flag of truce, the party composing it will be halted at such distance as to prevent any of them overlooking the posts, and will be detained until instructions are received from the outpost company commander. If permitted to pass the outposts, the individuals bearing it will be blindfolded and led under escort to the commander of the outposts. If the flag of truce bears a letter or parcel, it must be received by the commander of the outpost company, who will give a receipt, and instantly forward it to head-quarters. No conversation, except by permission of the commander of the outposts, is to be allowed on any subject.

17. Sentries must know the position of the sentries on their right and left, the position of the piquet and of any detached posts in the neighbourhood, the ground they have to watch, how to deal with persons approaching their posts the names of all villages, rivers, &C., in view and the places to which roads and railways lead, the ranges of points to the front.

Sentries must be alert and watch for the enemy and for signals from our own troops; they will give the alarm by message, not by firing, unless absolutely necessary.

A sentry will immediately warn his group of the approach of any person or party. When the nearest person is within speaking distance, the sentry will call out "Halt," covering him with his rifle. The group commander will then deal with the person or party according to the instructions received by him. Any person not obeying the sentry or attempting to make off after being challenged, will be fired upon without hesitation.

18. Except when challenging as above, no one is allowed to speak to persons presenting themselves at the outpost line except the commanders of the nearest piquet and outpost company, who should confine their conversation to what is essential, and the commander of the outposts. Prisoners and deserters will be sent at once, under escort, through the commander of the outpost company, to the commander of the outposts.

NOTE:-

A sketch of this description is very useful for teaching young officers and non-commissioned officers elementary map reading and field sketching. It can be reproduced from survey maps by means of wax sheet or hectograph. The class can be instructed to fill in detail of tactical importance on the ground, and by this method they will learn more in a limited time than they would if they set out to make a sketch in the first instance. All officers should be able to make a rough field sketch, to enlarge a map, and fill in detail of tactical importance, but elaborate mapping with special instruments should be left to experts.